The cables stretch above as you stand on a richly patterned and textured floor. A seemingly infinite set of repetitive curves are set off by rich red balusters and an angled roof through which light comes. This is the new architecture of music, courtesy Charles Brooks and his new techniques of microphotography.

The cables are those of a piano and the textured floor is the soundboard of a Steinway.

The Exquisite Architecture of Steinway, Part 7

Franz Liszt: Années de pèlerinage, 3rd year, S163/R10 – No. 4. Les jeux d’eau a la Villa d’Este (The Fountains of the Villa d’Este) (Tomas Dratva, Steinway piano)

The curves and the angled roof and the red balusters are the interior of a Fazioli grand.

Fazioli Grand Piano Part I

This is the inner beauty of an instrument that Charles Brooks’ new photographs show off in gorgeous detail. Your critical self says “Fazioli? Surely, they could have smoothed that out a trifle….”, and then you realize that this is wood blown up in an image so large that what you’re seeing is the grain. It is smooth, to the eye and the hand, but to the camera, it seems rougher than it really is.

We spoke with Mr. Brooks about his work, and he told us that this had begun as a lockdown project. As a cellist, he had no jobs; as a photographer, he could take images of musical instruments without the danger of disease. With some new probe lenses in hand, he took off the bottom spike of a cello and fed his lens in to capture the world of physical music.

Brooks’ look inside instruments includes wind instruments, and, in fact, his first subject was a flute, the 14k Burkark Elite Rose Gold Flute.

14K Burkark Elite Rose Gold Flute

This is where he discovered the problems of photographing in small spaces. Only a small part of the total image was in focus. But this is where he also discovered the secret inner history of an instrument: here it’s the scratches from the cleaning rod that show more than damage, they show the continual evolution of an instrument.

To solve the small focal point problem, software came to his rescue. All of these detailed images are combinations of hundreds of different images that give us a unique all-in-focus point of view.

He uses intense (and hot) lights to illuminate his subjects and that adds to the delay in picture-taking. It’s necessary to stop, shut everything down, and let the instrument cool off before another set of images can be taken.

His investigations into the secret inner worlds of instruments have been surprising. In one cello that had been rebuilt after it met a train, he found the unexpected: all the various luthiers who had worked on the instrument over the past century had all signed their work. The cello was made in Germany in the late 1800s and came to New Zealand before 1911. In the late 1920s, it was in an accident and was rebuilt. Dated luthiers’ signatures from 1911, 1930, and 1988 are on the inside, but not visible from the outside.

The photograph of another cello, built around 1780 by the English maker Lockey Hill, makes it seem like you’re looking into an antique hallway of wood, with an off-centre pole in the middle. Curly ceiling lights reflect on the floor. Here, you’re looking from the bottom of the cello up to the waist and the neck, in a picture taken through the hole where the cello spike goes into the instrument. The column is, of course, the sound post, linking the vibrations of the face and back of the cello. Our eyes read the light coming through the F-holes and give us the perspective, but the photographer has fooled us: this whole space is not 2 or 3 meters high but only 12 cm.

Lockey Hill Cello, Part I

Franz Benda: Violin Sonata No. 23 in C Minor, Lee III:9 – III. Allegro non molto (Hans-Joachim Berg, violin; Naoko Akutagawa, harpsichord)

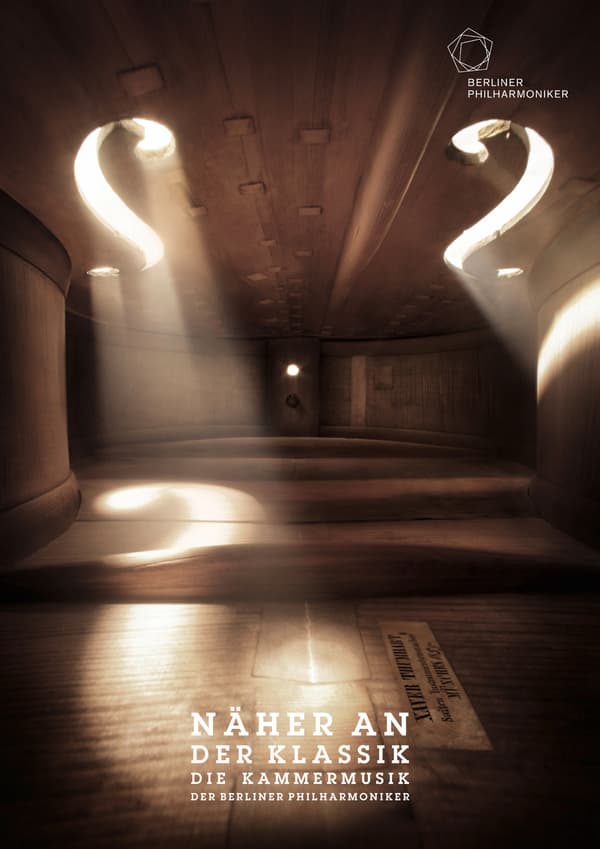

The only other set of comparable images he knows about was taken by the German photographers Studio Mierswa & Kluska for the Berlin Philharmonic in 2009. Revolutionary for their time and pieces of great beauty, the images show the unique inside beauty of instruments but also look like they hit the same problem with the focal point that Brooks ended up solving. In this double bass picture, the image was taken from the neck end and it’s more about the play of light on the floor than of the instrument itself. The technology of the time simply wouldn’t allow the multiple changes in focal point with the software to merge multiple, if not hundreds of images, that Brooks can achieve today.

Mierswa & Kluska: Berlin Philharmonic Double Bass, 2009

We can see immediately that the sound post is missing since it’s held in place solely by the pressure of the front and back faces of the instrument. The light at the end of the ‘room’ is the hole for the double-bass spike.

To meet the constant challenges he faces with photographing in small spaces, Brooks is working with medical imaging experts, who use truly tiny cameras to take videos of patients’ insides. He also modifies his own lenses, melting their casings to make them fit in smaller and smaller spaces. As he’s exploring the world of microphotography, he’s making his own innovations.

One of the most interesting instruments he’s photographed is the Australian didgeridoo.

Australian Yidaki Didgeridoo

Peter Sculthorpe: Earth Cry (William Barton, didjeridu; New Zealand Symphony Orchestra; James Judd, cond.)

The instrument is traditionally made from cylindrical pieces of wood that have been hollowed out by termites, hence the rough nature of the wood. The termites only attack the dead heartwood of trees like the eucalyptus; the live wood contains a chemical that they don’t like. The red colour on the left side is ochre from around the mouthpiece that has migrated down the tube. It’s a very different image than those of the more traditionally milled tubes of flutes.

See the photographer’s website at https://www.ArchitectureInMusic.com to see some amazing images that will make you rethink everything about an instrument. This is clearly the start of a project that can encompass the world: both the world of instruments and the constructor’s world in an instrument. His image of a guitar made by Chilean luthier Roberto Hernández shows, for example, a mix of modern and ancient construction techniques. His saxophone pictures show oxidizing from the players’ breaths and internal scratches from cleaning tools. In a world where things are increasingly machine-made, Brooks’ images preserve the handmade, the hand repaired, and the hand that cares for them.

He has an exhibition forthcoming in July 2024 at the Napa Valley Museum – there, he hopes to have a couple of room-sized images so you can, literally, walk in a cello or a piano. We look forward to seeing what falls under his lens next!

For more of the best in classical music, sign up for our E-Newsletter

I really enjoyed the photos of the inside of the cello; however, there was not a photo of the “dust bunny” that lives near the end pin hole.😊