Félix Le Couppey

I started piano lessons at the age of six, and it was a lot of fun. There were so many exciting things to explore, and thankfully I had a very nice and knowledgably teacher. At that age, I didn’t get bored with finger exercises and I just loved the first little piano pieces with cute and charming melodies. Many of these first etudes are custom-written for younger children—they certainly sound that way—which really doesn’t help beginning adult students. Nowadays there are countless piano methods on the market that promise to make the learning process easy and fun. At some point, however, you will still have to stumble across various etudes to strengthen your technique without numbing your brains. Finding etudes for your second or third years of piano studies that are both technically beneficial and musically entertaining isn’t an easy task. It was nevertheless a lot of fun finding interesting etudes composed for the intermediate-beginner pianist. Let’s get started with a graduated set of etudes by the French music teacher, pianist and composer Félix Le Couppey (1811-1887).

Félix Le Couppey: L’Alphabet, Op. 17

Félix Le Couppey: L’Alphabet, Op. 17

Félix Le Couppey was a student at the Paris Conservatoire, and by the tender age of 17 he was already employed at that institution as an assistant professor of harmony. He went on to receive the first prize in piano and harmony in 1825, and in piano accompaniment in 1828. Couppey became a full-time professor in 1837, and he taught piano at the Conservatoire from 1854 to 1886. He wrote a substantial number of textbooks on the piano, and an equally large number of studies and etudes. His most famous set is a series of elementary etudes called L’Alphabet. We find 25 etudes in total, and they do get progressively more difficult. These little charming didactic pieces offer an interesting approach to polyphony and harmony, and they are simply delightful.

Carl Czerny: Preliminary Studies to the

School of Velocity for piano, Op. 849

Any list of rudimentary etudes has to include the name Carl Czerny (1791-1857). So let’s get him out of the way. Czerny was greatly concerned about acquiring and maintaining piano technique, and he invested much time and energy in providing students with a graduated progress. He composed studies and etudes for all skill levels, and his Thirty New Studies in Technics, (Preliminary School of Velocity) Op. 849 bridges the gap between the Practical Method for Beginners, Op. 599 and The School of Velocity, Op. 299. Despite getting all the bad press, Czerny was a skilled pedagogue who tried to write pleasing compositions that combine musical potential and technical benefit.

Carl Czerny: Thirty New Studies in Technics, Op. 849

Cornelius Gurlitt

The German composer Cornelius Gurlitt (1820-1901) counted Robert Schumann and Johannes Brahms among his close personal friends. Like Brahms, he hailed from Hamburg, and he studied at the Leipzig Conservatory with the famed Carl Reinecke for six years. He first appeared publically at the age of seventeen, and subsequently decided to go to Copenhagen to continue his studies. While taking organ, piano, and composition lessons, Gurlitt became friends with Niels Gade.

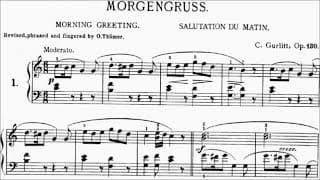

Cornelius Gurlitt: Morning Greeting, Op. 130 No. 1

Originally, Gurlitt took on a position as organist, and later moved to Leipzig where Gade was musical director of the Gewandhaus concerts. Always on the move, Gurlitt traveled to Rome and graduated as a Professor of Music in 1855. Returning to the Hamburg region, the Duke of Augustenberg engaged him as a teacher for three of his daughters. Gurlitt also worked as a military bandmaster, and then as an army conductor. He produced a vast number of compositions, including operas, songs, cantatas, and symphonies. But he is best known for his small and delightful piano works for students and amateurs. His 35 Easy Etudes, Op. 130 are charming musical miniature and portraits, prefaced by imaginative titles, that become gradually more challenging.

Cornelius Gurlitt: 35 Leichte Etüden, Op.130

Béla Bartók

Béla Bartók composed a good many of my favorite pieces during my initial years of piano studies. Bartók traveled throughout remote regions of Eastern Europe and North Africa to record folk music. The songs and sounds he gathered became a fundamental element of his musical voice, and he was highly enthusiastic of passing on these cultural treasures to subsequent generations. His Mikrokosmos, a collection of 153 piano pieces in six books of graded difficulty is a work of great pedagogical value. But it is not a conventional piano method. According to Bartók, “technical and theoretical instructions have been omitted, in the belief that these are more appropriately left for the teacher to explain to the student.

Bartók: Mikrokosmos III

The first four volumes of Mikrokosmos were written to provide study material for the beginner pianist and are intended to cover, as far as possible, most of the simple technical problems likely to be encountered in the early stages. The material in volumes 1–3 has been designed to be sufficient in itself for the first, or the first and second, year of study.” The large-scale Mikrokosmos occupied him for several years. Bartók described the genesis of his new piano work in 1940: “Already in 1926, I was thinking of writing very easy piano music for the teaching of beginners. However, it was only in the summer of 1932 that I really began working on it, and at that time I composed about 40 pieces; in 1933-34, another 40 pieces, and an additional 20 in the following years. Finally, in 1938 I had 100-odd pieces together. But there were still some gaps. I filled in these last year, and among others, completed the first half of volume one.” These fantastic pieces are arranged in order of difficulty, so it is very easy to tailor assignments to the abilities of the student.

Béla Bartók: Mikrokosmos, Vol. 3

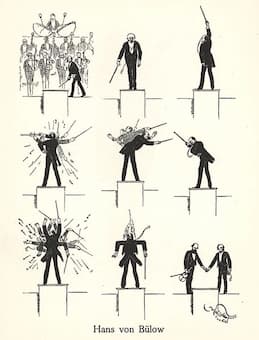

Hans von Bülow

Today, Hans von Bülow (1830-1894) is remembered as a highly influential conductor, and as the husband of Cosima née Liszt, who left him for Richard Wagner. What is frequently overlooked is his lasting influence as a pianist. During his American tour in 1876, a critic wrote, “Those who heard Hans von Bülow in recital, listened to piano playing that was at once learned and convincing. He was a deep thinker, analyzer; as he played one saw, as though reflected in a mirror, each note, phrase and dynamic mark of expression to be found in the work.” Bülow was one of the first performers to play the complete 32 piano sonatas by Beethoven, and contemporaries described him as the “greatest living authority on Beethoven.”

Hans von Bülow by Hans Schliessmann

In addition, Bülow premiered Liszt’s B-minor Sonata, and he also was one of the most successful pedagogues of the 19th century. He was employed in Frankfurt and Berlin and famous for his exacting master classes. Richard Strauss attended the Frankfurt classes and wrote, “I am rapidly coming to the conclusion that Bülow is not only our greatest piano teacher but also the greatest executant musician in the world.” Bülow’s legacy for today’s piano student is not expressed in original compositions, but in his precise editions. Aimed at players who might need technical and musical guidance, “Bülow’s editions offer very specific practical and artistic suggestions based on his own understanding of the works as teacher and performer.”

Jean-Baptise Duvernoy

Many of his editorial suggestions, such as pedal marks, dynamics, articulations, and musical commentaries are often explained at length in the prefaces and footnotes. Bülow favors long phrases, lyrical expression, and dramatic effects, which are achieved through fingering suggestions or by the addition or deletion of original slur marks and dynamics.” His prose footnotes explain how to execute certain passages in order to effectively bring out the appropriate expressions such as singing quality, humor, or drama—suggestions whose poetic and aphoristic style was also an important characteristic of his teaching.” And for the beginning student he edited a delightful collection of 25 Studies by the French pianist and composer Jean-Baptiste Duvernoy (1802-1880).

Jean-Baptise Duvernoy: École primaire, Op. 176

Christian Louis Köhler

The German pianist, composer, critic and teacher Christian Louis Köhler (1820-1886) was born in Brunswick and sent to Vienna to study music. He studied piano with the famed C.M. von Bocklet, and theory with the esteemed teachers Sechter and Seyfried. Köhler eventually settled in Königsberg, now Kaliningrad, and worked as a conductor in the local theatre. From 1847, Köhler devoted himself exclusively to piano pedagogy and to writing about music. He was music critic for the “Hartungsche Zeitung” and his correspondence articles from Königsberg for Brendel’s “Neue Zeitschrift für Musik” brought him to the attention of Liszt and Wagner in 1852. His first book, “The Melody of Language” established him as one of the leading German writers. In addition, Köhler remained influential throughout his career in the area of piano pedagogy. “He published collections of graded instructional pieces and books of exercises, published new editions of the works of Classical and Romantic composers, wrote widely disseminated books about piano pedagogy, and taught a great number of pupils. In all, he published over 300 original compositions, pedagogical works and editions, including 12 Easy Etudes, Op. 157.

Louis Köhler: 12 Kleine Etüden, Op. 157, No. 1-3

Ludvig Schytte

The Danish composer, pianist and teacher Ludvig Schytte (1848-1909) originally trained as a pharmacist. He received his first musical training at the age of 22, and made such rapid progress that he was still able to embarked on a successful musical career abroad. He took lessons from Niels Gade in Leipzig, Wilhelm Taubert in Berlin, and from Franz Liszt in Weimar in 1884.

Ludvig Schytte: Easy Characteristic Etudes, Op.95

Schytte was appointed at various conservatories in Vienna, and by 1907 he had settled in Berlin as a teacher at the Stern Conservatory. He composed an imposing piano concerto, and his expansive piano sonata “bears witness to a more serious approach to the problems of musical form.” However, Schytte was also considered a master of miniature forms, and he is primarily remembered for about 200 attractive piano pieces, some of which became extremely popular. He composed numerous pedagogical piano methods, of which his collections of Etudes, especially, opp. 75, 95, 106, 161 and 174, are still in widespread use.

Ludvig Schytte: Easy Characteristic Etudes, Op.95 (Excerpts)

Henri Jérôme Bertini

Henri Jérôme Bertini (1798-1876) was born in London, but quickly returned to Paris with his parents. He received his early musical education from his father and his brother, a student of Muzio Clementi. There was no doubt that Bertini was a child prodigy, and his father took him on a concert tour of England, Holland, Flanders, and Germany. After studies in composition in England and Scotland he was appointed professor of music in Brussels but returned to Paris in 1821. Robert Schumann reviewed one of Bertini’s trios, and wrote, “Bertini writes easily flowing harmony but the movements are too long. With the best will in the world, we find it difficult to be angry with Bertini, yet he drives us to distraction with his perfumed Parisian phrases; all his music is as smooth as silk and satin.” We also know that Bertini gave a concert with Franz Liszt on 20 April 1828, playing Bertini’s transcription of Beethoven’s 7th symphony for piano eight hands. Bertini’s playing was described as “having Clementi’s evenness and clarity in rapid passages as well as the quality of sound, the manner of phrasing, and the ability to make the instrument sing characteristic of the school of Hummel and Moschelès.” And let’s not forget that Bertini was a celebrated teacher who concentrated on strict pedagogy. In all, he published 20 books of roughly 500 studies for all levels and abilities.

Henri Bertini: 25 Studies, Op. 100

Giuseppe Concone

Giuseppe Concone (1801-1861) was one of the most influential singing instructors of his time. Originally born in Turin, he initially tried his hands at theatrical composition and produced an opera that failed to meet expectations. Discouraged he relocated to Paris to become a famous vocal and piano teacher. He published a good many books of vocal exercises that are still in use in vocal studios today. Specifically, he achieved worldwide recognition for a book of 50 solfeggi for a medium voice, 15 vocalizzi for soprano, 25 for mezzo-soprano, and a book of 25 solfeggi and 15 vocalizzi, 40 in all, for bass or baritone. “The contents of these books are melodious and pleasing, and calculated to promote flexibility of voice. The accompaniments are good, and there is an absence of the monotony so often found in works of the kind.” Concone returned to Turin after the French revolution of 1848, and he was appointed organist of the Royal Chapel. Besides publishing vocal primers, Concone also issued a collection of 15 Studies in Style and Expression for the piano. Sporting imaginative titles like “Anxiety,” “Melancholy,” “Robin Redbreast,” and “The Waves,” these etudes are especially appropriate for the early advanced pianist in developing appropriate expression and interpretation.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up for our E-Newsletter

Giuseppe Concone: 25 Etudes mélodiques, Op.24