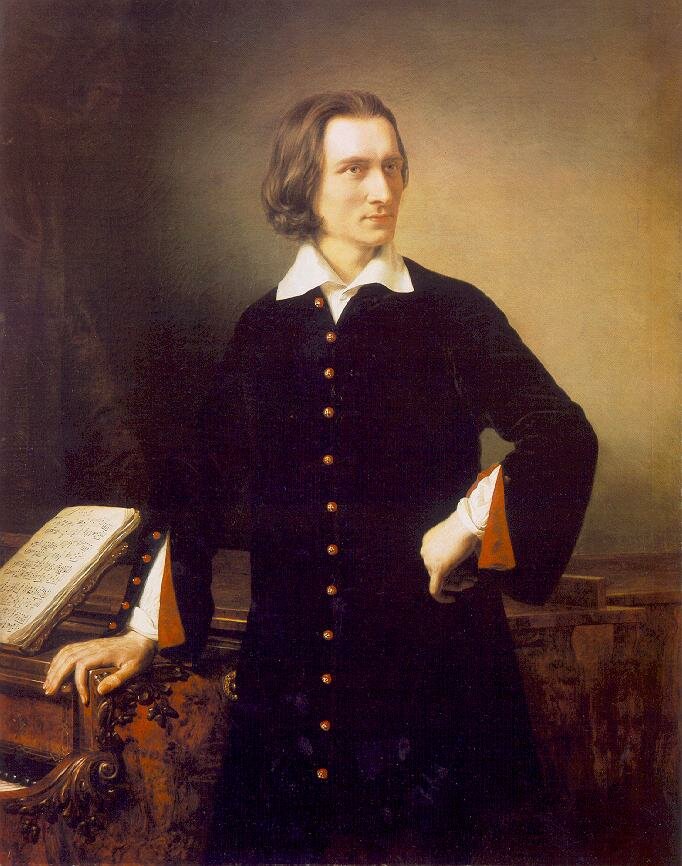

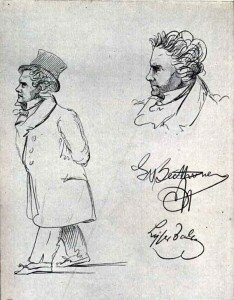

Sketch of Beethoven

Beethoven: Piano Sonata No. 8 in C Minor, Op. 13, “Pathetique”

Of the early sonatas, the most significant is the Pathétique (No. 8). Its slow, weighty introduction marks a break from Mozart and Haydn. This is music of depth and rhetoric. In contrast to the frenetic opening movement, the slow movement unfolds with a beautiful yet simple cantabile melody before a sense of anxiety and struggle return in the finale. The sonata demanded a more robust piano with a wider keyboard and more resilient strings to cope with the chords of the opening. The Viennese piano maker Streicher provided such an instrument and the development of the ‘modern’ piano took another significant step forward.

Beethoven: Piano Sonata No. 14 in C-Sharp Minor, Op. 27, No. 2, “Moonlight” – I. Adagio sostenuto

The Beethoven Broadwood

The pedal effect Beethoven desired is no longer possible on a modern grand piano due to its much greater resonance, so pianists seek to recreate the effect with more subtle use of the sustain pedal. A performance on Fortepiano offers a suggestion of the kind of effect Beethoven wanted:

Beethoven: Piano Sonata No. 21 in C Major, Op. 53, “Waldstein”

The ‘Waldstein’ Sonata (No. 21, composed 1804) was a breakthrough piece for Beethoven. Longer than his earlier sonatas, it is imbued with a sense of heroism and struggle which also characterises his later sonatas. Throbbing quavers signal the opening, giving way to a surprisingly tender second subject, while the mysterious, fragmented middle movement heralds the finale, which begins with a sweetly consoling melody and quickly transforms into daring octave scales in the left hand, a continuous trill in the right hand and heroic fanfares.

I shall look upon it as an altar upon which I shall place the most beautiful offerings of my spirit to the divine Apollo… As soon as I receive your excellent instrument, I shall immediately send you the fruits of the first moments of inspiration I spend on it, as a souvenir for you from me.

(Quote from a letter written by Beethoven to Thomas Broadwood in 1818)

Beethoven: Piano Sonata No. 29 in B-Flat Major, Op. 106, “Hammerklavier” – III. Adagio sostenuto

The ‘Hammerklavier’ (No. 29, composed 1817-18) was almost certainly written in response to a rather special gift – a new piano from English maker John Broadwood & Sons. More robust than its Viennese or French counterparts, the Broadwood had a six-octave keyboard and a heavier action which would have suited the repeated chord fanfares and complex passagework which characterise the opening movement. Additionally, a bigger instrument gave greater scope for expression, as in the hauntingly sad third movement. The finale is a finger-twisting fugue, the cumulative effect of which is an overwhelming expression of huge power and logic.

The Last Sonatas (Nos. 30-32) are considered to be amongst the most philosophical music, written when Beethoven was profoundly deaf, miserable and in ill health. And yet he wrote this deeply personal music which speaks of shared values, and what it is to be a sentient, thinking human being. Although structured in the Classical three-movement form, the sense of a through-narrative pervades these sonatas from the memorable, lyrical opening of the Op. 109 to the final fugue, that most life-affirming and solid of musical devices, of the Op. 110 to the “ethereal halo” that is contained in some of the writing of the Arietta of the Op. 111.

The piano sonata was now clearly established as a vehicle for pianistic prowess but also a broad range of emotion and expression, meaning and intent.