The Romantic Piano Sonata – Innovation within the Classical Form

Liszt

Schubert: Piano Sonata No. 21 in B-Flat Major, D. 960 – II. Andante sostenuto

Schubert revered Beethoven, and his hero’s influence tends to be seen in sonatas which share corresponding keys, most obviously in the late C minor sonata, D. 958. Schubert remained largely true to the classical sonata structure, but experimented within that structure. During the 1820s, he began to use cyclic devices in his sonatas, whereby motifs or themes established in the opening movement recur elsewhere, often subtly modified, to create an enhanced sense of “belonging” and a continuous narrative between the various sections and movements. These simple devices represent his boldly experimental approach to traditional sonata form, further enhanced by a dramatic, lyrical expansiveness (what Schumann called his “heavenly length”) and daring underlying harmonies which create contrasting and often startling musical hues and unexpected shifts of emotion.

Beethoven is the powerful declaimer, but Schubert speaks more quietly, his music often introspective and solitary. In the late sonatas in particular, the heavenly length of these works creates a sense of stasis, of time suspended, and of a composer looking inward, searching his soul, though without bitterness or resignation.

Chopin: Piano Sonata No. 2 in B-Flat Minor, Op. 35, “Funeral March” – II. Scherzo

Chopin

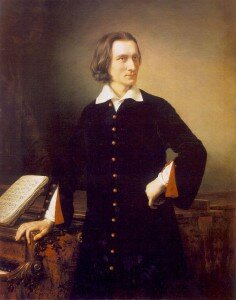

Liszt: Piano Sonata in B Minor, S178/R21

Alfred Brendel has called it “the most original, powerful and intelligent sonata composed after Beethoven and Schubert” and Liszt’s B-minor Piano Sonata is regarded as one of the “greats” in the pantheon of piano literature. It is not a bravura nor poetic piece. In its structure it references both the Classical sonata form as conceived by Haydn and Mozart and continued by Beethoven and Schubert, and the looser term “sonata”, meaning an instrumental work in four movements (exposition, development, recapitulation and coda). In the Sonata, Liszt combines all these meanings into a single movement – and by doing so he also continues what Schubert explored in his Wanderer Fantasy (a favourite concert piece of Liszt) and late piano sonatas, where the sections of the work are linked via distinctive themes or motifs. While some have attempted to ascribe a narrative to this monumental work, for others it is simply a piece of expressive form, with no meaning beyond itself. Certainly, the composer never offered any explanation for it. In its powerful outbursts and clashing harmonies it looks ahead to the twentieth century, while the notion of a single movement “sonata” or “fantasy sonata” was taken up by composers such as Scriabin, Medtner, Prokofiev and Berg.

Scriabin: Piano Sonata No. 5, Op. 53

Scriabin was an heir to the Classical and Romantic sonata, using the structure as the vehicle for his own distinct musical language and expression. Through his ten piano sonatas, of which six are scored as single-movement works, the sonata form survived into the twentieth and twenty-first centuries.