Why are there so many words when it comes to music? And in so many languages, like Italian, German, French, and even English! Often, one has to decipher obscure words to read the score and the musical directions, which include instructions for the dynamics, the style, the speed, the volume. There are just too many to learn!! Don’t panic. We’re here to help. These are a few essential definitions to remember.

Accidentals: Wrong notes.

Accidentals: Wrong notes.

Ad Livitum: Play freely and with anger.

Agnus dei: A famous female church composer.

Andante: Easy walking pace to hell.

Alleregretto: When you’re several bars into the piece and realize you’ve started too fast.

Apologgiatura: A piece you’re sorry you’re playing.

Approximatura: Notes played with intention and conviction even if they weren’t written by the composer.

Approximento: A musical entrance that is vaguely the right pitch or rhythm.

Baroque: When you haven’t had many gigs and can’t go shopping.

Canata: A choral work that uses solo voices with an impossible instrumental part, which you can’t play.

Cello: The proper way to answer the phone.

Conductor: Someone who organizes a scheme with a hidden agenda.

Corona: A held note, grand pause, performed at home alone, and 6 feet away from others.

Decapitulation: Losing your head when the melody comes back but in another key.

Dill Piccolini: A tiny wind instrument, which only plays sour notes.

Diminished fifth: An empty bottle of Jack Daniels.

Diminished fifth: An empty bottle of Jack Daniels.

Fagotto: When you didn’t remember your bassoon or the time of the rehearsal.

Fermantra: A note or drone held over and over and over.

Fiddler Crabs: 100 species of cantankerous violinists.

Flute Flies: Tiny insects that descend on poor unsuspecting musicians during outdoor concerts.

Frugalhorn: A cheapskate brass player who uses an inexpensive beat-up brass instrument.

Glissando: A sliding technique adopted by string players for difficult runs.

Harmoney: The simultaneous combination of pitches, when blended into chords pleasing to the ear and the pocketbook.

Interval: How long it takes to find the right note, or a drink during intermission.

Karajan: The famous conductor who traveled light.

Lamentoso: To play sadly with handkerchiefs.

Major scale: What you say after hiking up a mountain: “That was a major scale!”

Melodic Minor: A 12-year-old playing Tchaikovsky Concerto.

Metronome: A diminutive musician who plays on the underground.

Obligato: Being forced to practice or being compelled to play your part accurately, which has a million fast notes, while the rest of the ensemble holds long tones.

Obloe: The instrument that takes a lot of hot air to play.

Obstinato: A repeating rhythmic phrase, which gets stunk in your head and refuses to stop.

Passing tone: Frequently heard near the baked beans at family barbecues.

Perfect Pitch: When you throw a banjo and it lands on bagpipes.

Orcastra: A pod of musical whales.

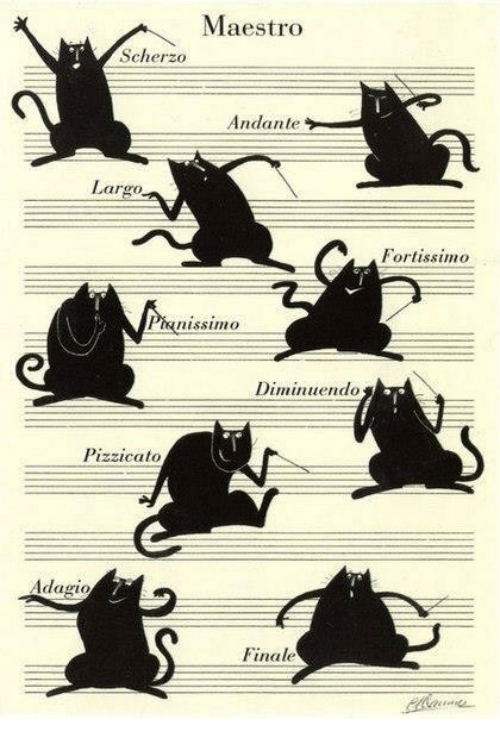

Pizzacato: When you’d rather stop practicing your plucking, and find your cat got into the pizza.

Pizzacato: When you’d rather stop practicing your plucking, and find your cat got into the pizza.

Relative major: An uncle in the Marine Corps

Risoluto: Indication to orchestras that they should stubbornly maintain the correct tempo whatever the conductor tries to do.

Spritzicato: The indication in the music to produce a bright, bubbly sound.

Sfortztando: Forcefully stand up and leave the stage.

Tempo Tantrum: When the conductor realizes the orchestra isn’t following.

Treble Clef: The higher it gets the more treble for players, who might fall off the clef.

Tremolando: The trembling effect when you see the word SOLO written in your part.

Tchaikovsky: Francesca da Rimini (Queensland Orchestra; Muhai Tang, cond.)

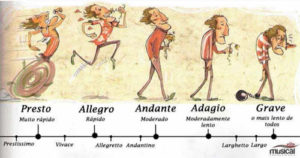

All over the world the training musicians receive is standardized. While we learn how to master our instruments, each performer also studies the international language of musical notation, terms developed to describe techniques, and styles.

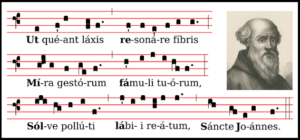

The first known written music, and the version we know today of a head-and-stem on a staff, was devised by Guido de Arezzo around 1000 AD. Features such as note values, time signatures, and directions were gradually added. During the Renaissance music flourished in Italy and composition was standardized and printed with Italian vocabulary. As time went on composers in other countries wrote indications in their native language. But these too are consistent musical terminologies. I know a smattering of Italian, German, and French simply from my musical studies!

The first known written music, and the version we know today of a head-and-stem on a staff, was devised by Guido de Arezzo around 1000 AD. Features such as note values, time signatures, and directions were gradually added. During the Renaissance music flourished in Italy and composition was standardized and printed with Italian vocabulary. As time went on composers in other countries wrote indications in their native language. But these too are consistent musical terminologies. I know a smattering of Italian, German, and French simply from my musical studies!

Bruckner: Symphony No. 9 in D Minor, WAB 109 – I. Feierlich: Misterioso (Stuttgart Radio Symphony Orchestra; Carlo Maria Giulini, cond.)

Tremolo notation for the strings in Bruckner’s symphony

Some examples of the indications we interpret in addition to reading the notes, rhythms, and dynamics— glissando, or sliding on the string, pizzicato or plucking, and harmonics. Tremolo or tremolando, which means quivering, can be written for piano, timpani, or for the string-player’s right hand, produced by moving the bow back and forth extremely fast, as in Bruckner Symphonies, (Sibelius and Tchaikovsky used this technique a lot too), or it can be written for the left hand, trilling from one note to another, as in Ravel’s Tzigane for violin and orchestra. Watch as Joshua Bell performs this piece and demonstrates these techniques.

Tempo rubato meaning to play freely, can be seen 32 seconds into the video. Examples of glissando, sliding up or down the string, which are typically marked by a line from one note to another, occur one minute in, at rehearsal number 1. Don’t they sound enticing! The fermata or pause sign at 4:30, indicates one should hold the tremolo fluttering notes. After rehearsal number 4 a long passage of left hand tremolo follows.

The ghostly, whistling sounds or harmonics, are achieved by not pressing the string firmly down. These are notated by hollow, diamond shaped notes seen at 5:29, rehearsal number 7, and they continue through number 8. The plus signs (+) an instruction to pluck the strings with the left hand, a difficult undertaking, occur at 6:25 number 11, and after number 21. Eerie harmonics return at number 14. Accelerando poco a poco, tells the performer to play faster and faster little by little, with breathtaking results.

There are many other terms to learn, and fun sounds to make, (harmonic bird calls?) such as in this Hungarian Gypsy tune Kanári (Canary) played by the Lakatos family (video at the top of the page). The complexities of reading music are astonishing and when coupled with musical profundity we as audience members are stirred, humbled, and moved.

Janet- this was a delightful article ! With a soupçon or two of truth…