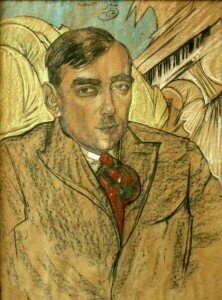

Portrait of Karol Szymanowski by Stanislaw Ignacy Witkacy

Vladimir Ashkenazy

Chopin: Mazurka No.1 in F sharp minor Op.6 No.1

Mazurka No.3 in E Op.6 No.3

Mazurka No.5 in B flat Op.7 No.1

Chopin’s Mazurkas show great range and variety. Some are lively, full of rhythmic vitality, others more soulful and melancholy. They are some of Chopin’s freshest and most original works, yet all retain features of their folk origins. One of the last Mazurkas, indeed one of his final works, Op. 68, No. 4 in F minor, is one of the most plaintive and heart-rending pieces Chopin ever wrote, suffused with poignancy with striking, sliding chromaticism, and an interesting marking (Chopin’s own) after the Trio, senza fine, literally “without end”, suggesting that instead of a regular da capo al fine, the piece should go on indefinitely, or simply fade away to nothing.

Typical Mazurka rhythm with the emphasis on the third beat

Chopin’s composition of Mazurkas suggested new ideas of nationalism in music, and influenced and inspired other composers, mostly eastern European, to support their national music. Franz Liszt was a big mover and shaker in this respect, claiming (somewhat inaccurately) that Chopin had been directly influenced by Polish national music. What is more likely is that Chopin heard national music of his homeland when he was growing up. When he left Poland, never to return because of the political climate, the Mazurka and the Polonaise became central genres in his compositional output, allowing him to retain a connection to his homeland.

Fellow countryman, Karol Szymanowski (1882-1937) wrote two sets of Mazurkas, Opus 50 and 62 (22 works in total). He drew musical influences from Chopin, but also from Wagner, Richard Strauss, Max Reger, Scriabin, Debussy, Ravel and nationalists Smetana and Bartok.

Marc-André Hamelin plays Szymanowski’s Mazurkas Op. 50 No. 1

Szymanowski travelled extensively, and from the 1920s he spent a great deal of time at the resort of Zakopane, in the Tatra highlands of Poland, where he discovered the local folk music or Górale. With its typical rustic fiddles and flutes, drone basses and pedal points, this became the template for his own music. Like Chopin, he was loyal to the idea of musical nationalism, but neither was he intimidated by it. So, while retaining many of the traditional features of the Mazurka in all its forms (Oberek, Kujawiak and Mazurek), he also extended it beyond the strict 4-phrase dance measure. As a result, Szymanowski’s Mazurkas defy the traditional symmetry of the dance, and instead expand and contract. The longest are just over three minutes long, the shortest just under two. Some are wistful, plaintive and meditative, others bounce and leap, some are witty and acidic, others are just rough and noisy. Within each one, tempos contract and expand, and one might find a slow Kujawiak-inspired passage right next to a section which is pure Oberek. It is these clever juxtapositions which give Szymanowski’s Mazurkas such life and piquancy.

Marc-André Hamelin plays Szymanowski’s Mazurkas Op. 50 No. 2

Absolutely heartbreaking, heavenly music