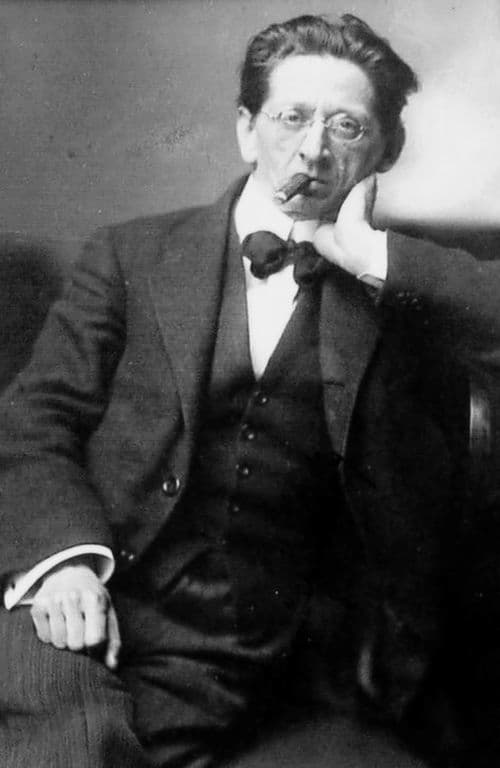

Austrian composer and conductor Alexander von Zemlinsky (1871–1942) was in the middle of the innovations of the Second Viennese School, with Arnold Schoenberg (1874–1951) as his pupil. However, despite their common location and close age, Zemlinsky was not the revolutionary in music that Schoenberg became.

Alexander von Zemlinsky

In his musical life as a teacher, he taught the best in Vienna: Berg, Webern, and later, Korngold. His operas won prizes, Mahler conducted the premiere of his second opera in Vienna, and in 1901, Schoenberg married his sister Mathilde. Later that year, Zemlinsky became involved with his pupil, Alma Schindler, considered the most beautiful girl in Vienna; after a year of a relationship, she rejected him in favour of Mahler, citing his lack of height and unattractive appearance as factors.

Alma Schindler, 1900

In February 1902, following this rejection, he began work on what he called his ‘symphonic poem’, Die Seejungfrau (The Mermaid), based on the story by Hans Christian Andersen. Seen as a reaction to Schindler’s rejection, the music has emotional intensity not generally felt in music from Vienna at this time.

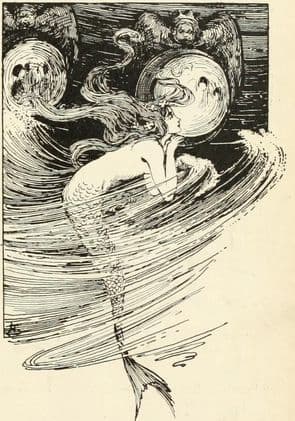

As we know from Andersen’s story, the mermaid falls in love with a handsome prince she sees on a ship.

Helen Stratton: The Little Mermaid: The mermaid sees the prince

on the ship, 1899

The ship founders and she rescues the prince, but he is unaware of her role in delivering him from death.

Helen Stratton: The Little Mermaid: The mermaid rescues the prince, 1899

The mermaid begs the Sea Witch for legs so she can go on shore to meet her prince but is told the price: if she doesn’t obtain a soul through love and marriage, if her beloved marries someone else, the mermaid will die and will dissolve into sea foam.

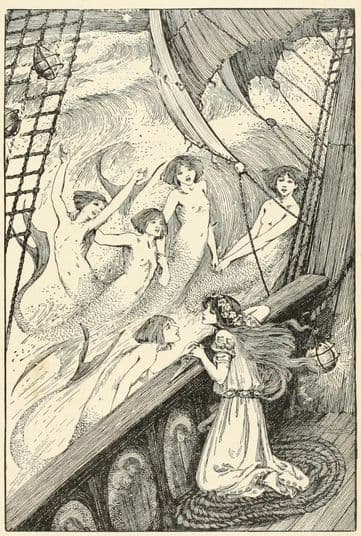

The prince thinks a princess from the neighbouring kingdom was his rescuer from death and so marries her out of mistaken gratitude. This means death for the mermaid. As she faces the sea, her sisters arrive, all with short hair. They have given their locks to the Sea Witch in exchange for a knife. The Sea Witch has offered her a redemption: if she kills the prince with the knife and lets his blood drip on her feet, she can return as a mermaid. Given the knife by her sisters, the mermaid decides she cannot do as requested by the new bridegroom and returns to the water to die.

Helen Stratton: The Little Mermaid: The mermaid sisters give the knife

to The Little Mermaid, 1899

When she dissolves into sea foam, she finds she has turned into a daughter of the air because of her selflessness. The other spirits tell her that If she does good deeds for the next 300 years, she will obtain the same immortality as men receive when she ascends to heaven.

Zemlinsky’s opening is not about the bright life of the mermaid at sea, but a dark and foreboding vision of the future. We soon, however, seem to descend into the depths of a happier sea. Zemlinsky, although he started out writing a ‘symphonic poem’, which implies a set storyline, ended up creating a work that is more like a panorama of colours and moods.

Alexander Zemlinsky: Die Seejungfrau (The Mermaid) (critical edition by A. Beaumont) – I. Sehr massig bewegt (Helsinki Philharmonic Orchestra; John Storgårds, cond.)

Although he had created a detailed programme for at least the first movement, he discarded it. He also discarded many musical ideas that would have been illustrative of the detailed programme.

The second movement did not follow a detailed programme, but Zemlinsky did provide a few cue words. The movement opens with a complete change of mood: the storm is upon us.

Zemlinsky cut a 14-page section entitled ‘in the realm of the Mer-Witch’ – literally, removing the pages and putting them back into his sketchbook. They have been included in this recording.

Alexander Zemlinsky: Die Seejungfrau (The Mermaid) (critical edition by A. Beaumont) – II. Sehr bewegt, rauschend (Helsinki Philharmonic Orchestra; John Storgårds, cond.)

The final movement had no programmatic references at all. When we get to the final minutes, we are swept up in a transcendent climax as our child of the sea becomes a spirit of the air, in triumph.

Alexander Zemlinsky: Die Seejungfrau (The Mermaid) (critical edition by A. Beaumont) – III. Sehr gedehnt, mit schmerzvollem Ausdruck (Helsinki Philharmonic Orchestra; John Storgårds, cond.)

When the work received its premiere at a concert of the Vereinigung schaffender Tonkünstler in Wien (Association of Creative Musicians in Vienna), which had been founded by Zemlinsky and Schoenberg with the support of Mahler, it was on a program with Schoenberg’s Pelleas and Melisande. Both artists chose to forego any programme notes, presenting the pieces as ‘pure’ music.

Lacking a program that an audience could follow, beyond the evocative title, the work at its premiere was not billed as a ‘symphonic poem’ but rather, as a ‘fantasy for orchestra’. In using Andersen’s Little Mermaid story, he turns it inside out – in his own life, he, as the merman, was rejected by the princess. He couldn’t, however, become a spirit of the air, doing good around the world, he had to continue to live in Alma’s Vienna, knowing that she despised him. In a letter to her, he said: ‘“You stress as often as you possibly can how ridiculously insignificant I am and how little I have, how much makes me unsuitable to belong to you! Have you got so much to give, such an infinite amount, that other beggars object?! You are very beautiful, and I know how much I appreciate such beauty. But what about later, in 20 years’ time???” The couple split apart by the end of 1901, and he started writing this fantasy shortly thereafter.

The critics loved Die Seejungfrau, calling it ‘charming’, ‘poetical’, and ‘heart-warming’. The music, with its transparent orchestration, rich harmonies, and climaxes appealed to the ear and Zemlinsky, as the conductor at the premiere, would have known how to bring out all the subtleties of the score.

At later performances in Berlin and Prague, critical approval began to fall away and, in the end, Zemlinsky also had second thoughts. In a list of his works he made in 1910 for his publisher, this work was missing. He withdrew the score from the public and there were no performances of the work after 1908. Zemlinsky gave a major part of the score to his friend Marie Pappenheim, the Viennese socialist, writer, and physician. She wrote the monodrama Erwartung for Schoenberg after he was impressed with some of her early poems. She also did work with Milhaud and Ibert.

The work came back to the world’s attention in 1984, The score (and the lost Mer-witch section) was found again and a critical edition, edited by Antony Beaumont, was prepared in 2013. Beaumont created two versions of the second movement, one with the missing Mer-witch section and one without. With the rediscovery of the greatness of Zemlinsky’s orchestration and writing, a revival of the work is underway.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up for our E-Newsletter