New York Philharmonic

Lunar New Year Celebration

Long Yu, conductor; Yiwen Lu, erhu

January 31, 2023

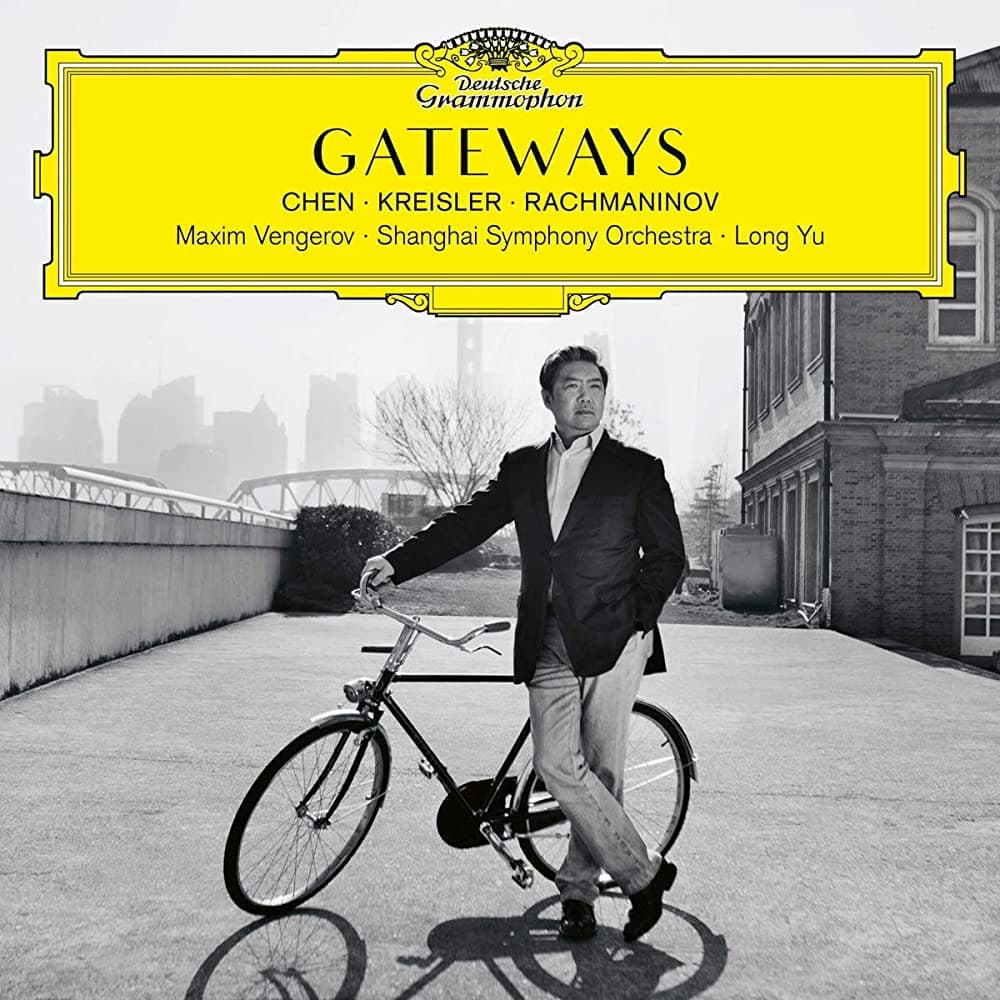

The highlight of the New York Philharmonic’s Lunar New Year concert this year, Qigang Chen’s 2017 composition La joie de la souffrance (The Joy of Suffering) is an unusually accessible contemporary work that has hooked me since I first encountered it on Gateways, an outstanding 2019 album by the Shanghai Symphony Orchestra under its conductor Long Yu.

In its original form La joie de la souffrance is a sort-of violin concerto. “Sort of” because instead of following the traditional three-movement concerto form, it unfolds, over twenty-five minutes, in ten continuous sections played without pause that Chen has described as “waves of emotion.” The somber early sections, which have titles like “Despair” and “Divinely alone,” foreground the solo instrument (Maxim Vengerov on the recording) as it stirs to life and eventually gives voice to a plaintive melody. The pace abruptly quickens in the later sections “Thrilled by illusions” and “Get caught up in the madness,” in which the violin skips over and around staccato accompaniment from the orchestra. If you like the Prokofiev violin concertos, you will respond to these passages in La joie. The work ends close to where it began, with haunting lines from the soloist, but now a certain serene quality prevails, in contrast to the opening’s pervasive sense of desolation.

Maxim Vengerov plays Qigang CHEN’s “La joie de la souffrance” Violin Concerto

My enthusiasm for Chen’s concerto only deepened when I caught its U.S. premiere in November 2019, with Xian Zhang conducting the New Jersey Symphony Orchestra and Ning Feng on solo violin. For the New York Philharmonic’s Lunar New Year performance, however, we were given a new version of the work, reconfigured from violin to erhu, the traditional Chinese two-stringed instrument here played by Yiwen Lu, and with lighter scoring for the orchestra.

Yiwen Lu

In the authoritative hands of maestro Long Yu, who has led the world premieres of both the violin and erhu versions of the work, La joie quickly exercised its familiar spell. If the sound of the erhu brought a more traditionally Chinese strain to this hybrid of Eastern and Western influences, that seemed only fitting at a concert celebrating the Year of the Rabbit.

Erhu Concerto La joie de la souffrance

Listeners can be grateful to Chen for dispensing with the cliché that music ostensibly concerned with suffering requires the audience to suffer too. This was an attractive sound world in which harp, marimba, and xylophones were only some of the instruments providing colorful accents. Chen has lived in France on and off for decades (he was Olivier Messiaen’s last student, back in the 1980s) and would seem to have absorbed a lot of what makes 20th-century French music so alluring—its sensuousness and precision detailing in particular.

If my seat in a right-tier box sometimes made it difficult to hear Lu over the orchestra in the louder passages, compensation came in the brief, crystal-clear dialogue between her instrument and Pascual Martínez Forteza’s clarinet, a poignant moment of connection that hadn’t registered with me in my earlier experience of the work.

Gateways © Deutsche Grammophon

The expressive range of the erhu became even more evident, meanwhile, in Lu’s solo encore, during which she coaxed a startling array of sounds from her instrument. One minute I thought I was hearing Appalachian bluegrass fiddle, and in the next, I would have sworn that a theremin had suddenly materialized on the David Geffen Hall stage.

Ultimately I’m not sure that the smaller-scale version of La joie de la souffrance holds quite the same expressive power as the brawnier original. Yet getting to hear the piece live, for a second time, brought home its import for me in a way that the recording, as good as it is, never quite has.

A title like “The joy of suffering” might suggest a slightly glib paradox. But by unfolding in one continuous movement rather than in discrete units, the work can be said to posit human experience as a spectrum—one in which joie and souffrance, rather than being diametrically opposed counterparts, co-exist side by side and even partake of each other’s qualities. (A notion that unmistakably feels more intuitive after all the ordeals of a multi-year pandemic.) Concise, direct, and gorgeous, Qigang Chen’s concerto is worth seeking out in whichever form you get to hear it.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter

Jeff Tompkins is a writer and ESL teacher in New York City. His work has appeared in The Brooklyn Rail, CHA Review of Books and Films, and Words Without Borders, among other outlets. He has been attending New York Philharmonic concerts for almost twenty years.