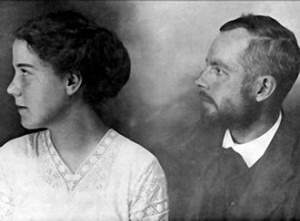

When Stefi Geyer rejected Béla Bartók’s proposal of marriage, the composer fell into a deep depression. Unable to sleep, he lost his appetite and obsessed with not being able to attain something he truly desired. And for many years to come, the “Stefi Geyer” theme from his first violin concerto served as a musical signpost for his mental anguish. His mood gradually brightened as he drew emotionally closer to a teenage girl named Márta Ziegler. She was the daughter of an inspector-general of the Budapest police, and together with her sister Herma had been studying privately with Bartók since 1907. Márta later recalled, “Béla was always teaching, he gave of his own experience and wanted to make his circle more developed and learned. He acquainted my older sister and me with the Pest museums and galleries while we were still his pupils. He taught us the names of the stars, how to prepare the insects and moths that he collected, he acquainted us with the poetry of Endre Ady’s and his beloved French writers: Flaubert, Maupassant, Daudet and one of his best-loved books Jacobsen’s Niels Lyhne. He also used to play unknown works for me on the piano in the evenings he was not too busy and I had to guess the composer.”

When Stefi Geyer rejected Béla Bartók’s proposal of marriage, the composer fell into a deep depression. Unable to sleep, he lost his appetite and obsessed with not being able to attain something he truly desired. And for many years to come, the “Stefi Geyer” theme from his first violin concerto served as a musical signpost for his mental anguish. His mood gradually brightened as he drew emotionally closer to a teenage girl named Márta Ziegler. She was the daughter of an inspector-general of the Budapest police, and together with her sister Herma had been studying privately with Bartók since 1907. Márta later recalled, “Béla was always teaching, he gave of his own experience and wanted to make his circle more developed and learned. He acquainted my older sister and me with the Pest museums and galleries while we were still his pupils. He taught us the names of the stars, how to prepare the insects and moths that he collected, he acquainted us with the poetry of Endre Ady’s and his beloved French writers: Flaubert, Maupassant, Daudet and one of his best-loved books Jacobsen’s Niels Lyhne. He also used to play unknown works for me on the piano in the evenings he was not too busy and I had to guess the composer.”

Béla Bartók: 3 Burlesques, No. 1 “Quarrel”

On 16 November 1909, Bartók took the sixteen-year-old Márta for a walk. When they stopped at his mother’s house, she asked if Márta was staying for dinner. It was then that

Bartók revealed to her that they had just gotten married! Their son Béla Jr. was born on 22 August 1910, and Márta became deeply involved in the process of transcribing and editing the folk songs Bartók recorded during his extensive field trips. Eventually, he would even take his young wife on long research trips to Algeria and other far flung places. He also completed and published several sets of piano pieces that were conceived during the early stages of his relationship with Márta. A draft of the Burlesque No. 1, “Quarrel,” which is dedicated to Márta, shows an amusing entry. Bartok writes, “Please choose one of the titles: “Anger because of an interrupted visit,” or Rondoletto à capriccio,” or “Vengeance is sweet,” or “Play it if you can” or “November 27.” Bartók and Márta, so it seemed, were a perfect private and professional match.

Yet there were distractions, as there always are. In the summer of 1915 Bartók was introduced to Klára, the teenage daughter of a chief forestry engineer. Klára was intelligent and strong-willed and had a keen interest in poetry and literature. Ten of her poems were published in a local journal, and Bartók fell deeply in love. He proposed divorcing Márta in order to marry her, but Klára was not remotely interested in marrying a man twenty years her senior. Eventually Bartók broke off the relationship, which created enormous psychological turbulence for him and his marriage. The direct outcome of this liaison was a set of Five Songs Op. 15. Klára had written the words to four of the five songs, with individual titles like “My Love,” “Nights of Desires,” and “In Vivid Dreams” conveying her sexual awakening. Bartók was well aware of the potential scandal and claimed to have written the texts himself. Yet nobody believed him and rumors started to spread.

Although deeply wounded, Márta decided to overlook her husband’s indiscretion. She also consented to her husband’s and her son’s conversion to Unitarianism on 25 July 1916. Father and son joined the Mission House Congregation of the Unitarian Church in Budapest, and Bartók briefly chaired the music committee. Bartók also drew his entire family into an exercise and community living approach termed “Freikörperkultur,” which loosely translates as “Free Body Culture.” It advocated a naturistic communal experience of being nude, but without a direct relationship to sexuality. Bartók and his family would exercise in their front garden completely naked, causing rather bad relations with the neighbors. Márta later recalled, “Bartók would exercise naked each morning and take the sun as early as possible. He could stand the sun particularly well and while sunbathing he would go on working, studying languages, scoring his compositions.” It was even reported that Bartok worked six to eight hours a day on the score of Bluebeard’s Castle in his solarium wearing only a pair of sunglasses.”

Márta was willing to overlook a great deal, however, she was not about to turn a blind eye in 1923, when Bartók had once again fallen in love with a young piano student. The new object of his attention was the 19-year-old Edith Pásztory, and after a heated exchange with his wife, Bartók sent Márta to her home territory of Transylvania with their son Béla. Márta, so it seems, was told not to return. Apparently it was Márta’s suggestion that they should divorce, which they did without acrimony in June 1923. Two months after the divorce, Bartók married Ditta and their son Péter was born in 1924. But that’s the subject of our next episode.

You May Also Like

- Playing in Pairs: Bartók’s Concerto for Orchestra Béla Bartók’s Concerto for Orchestra challenges the educated listener on several fronts, starting with the title itself.

- In the Service of Music

Béla Bartók and Ditta Pásztory Béla Bartók had always been interested in young girls. His first wife Márta was only sixteen when they married - Béla Bartók

“Competitions are for horses, not artists” Bartók wrote, “The Dance Suite is the intimate result of my researches and love for folk music.” -

Béla Bartók—Composer, Countryman and Collector Béla Bartók my father’s Hungarian countryman, is considered a composer of profound influence in the 20th century.

Béla Bartók—Composer, Countryman and Collector Béla Bartók my father’s Hungarian countryman, is considered a composer of profound influence in the 20th century.

More Love

- Untangling Hearts

Klaus Mäkelä and Yuja Wang What happens when two brilliant musicians fall in love - and then fall apart? -

The Top Ten Loves of Franz Liszt’s Life Marie d'Agoult, Lola Montez, Marie Duplessis and more

The Top Ten Loves of Franz Liszt’s Life Marie d'Agoult, Lola Montez, Marie Duplessis and more - Mathilde Schoenberg and Richard Gerstl

Muse and Femme Fatale Did the love affair between Richard Gerstl and Mathilde Schoenberg served as a catalyst for Schoenberg's atonality? - Louis Spohr and Marianne Pfeiffer

Magic for Violin and Piano How did pianist Marianne Pfeiffer inspire a series of chamber music?