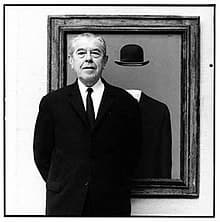

Lothar Wolleh: René Magritte, 1967

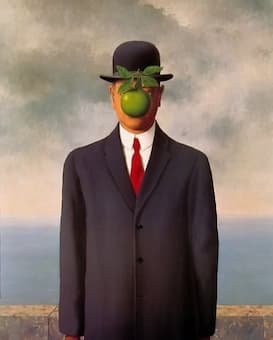

One of the most enduringly influential members of the Surrealist movement René Magritte is best known for his illusionistic images that challenged the viewer’s preconceptions of reality. Magritte once said, “my painting is visible images which conceal nothing; they evoke mystery and, indeed, when one sees one of my pictures, one asks oneself this simple question, ‘What does that mean?’ It does not mean anything, because mystery means nothing, it is unknowable.” Some of his most iconic paintings feature pipes, bowler hats, clouds, and green apples, common items rendered unfamiliar or deliberately mislabeled.

René Magritte: The Son of Man

“With his pictorial and linguistic puzzles, Magritte made the familiar disturbing and strange, posing questions about the nature of representation and reality.” As Magritte explained, “everything we see hides another thing, we always want to see what is hidden by what we see.” Magritte was born in Lessines, Belgium on 21 November 1898 to Leopold Magritte, a wealthy tailor and textile merchant, and Regina née Bertinchamps. He studied at the Académie Royale des Beaux-Arts in Brussels. Magritte started his career as a graphic artist and abstract painter, “but his work underwent a transformation in 1926 when he began to reinvent himself as a figurative artist.”

Walter Arlen: Septet, VII “After Magritte” (Rebecca Nelsen, soprano; Daniel Wnukowski, piano)

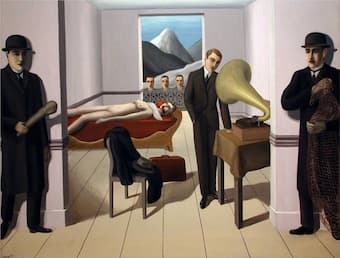

René Magritte: The Menaced Assassin

In 1927, Magritte produced his oil painting The Menaced Assassin, a canvas that helped launch his career as a Surrealist painter. It marked the beginning of his constant interest in severing the links between surface and essence. A critic writes, “the deadpan style would become his hallmark, each figure appears as though in a state of suspended animation. Cinematic in its staging, the gramophone is replaying the screams of the murdered woman, and the scene suggests a menacing narrative, but the specifics remain elusive, the visual details hard to reconcile into a single, coherent storyline.” Magritte moved to Paris in September 1927 to join an expanding Surrealist circle. That movement had originated as a literary movement in the late 1910s and early 20s and experimented with a new mode of expression that “sought to release the unbridled imagination of the subconscious. With his 1924 publication, The Manifesto of Surrealism, the poet and critic André Breton elevated the movement to international intellectual and political significance.

John Tavener: 3 Surrealist Songs, No. 1 “To René Magritte” (Dorothy Dorow, soprano; Rudolf Jansen, piano)

Lothar Wolleh: René Magritte

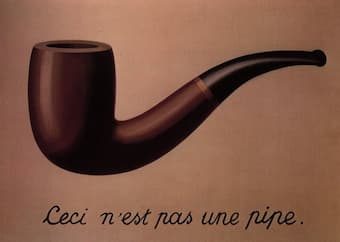

While Breton and his followers “tended toward a style of biomorphic abstraction achieved through automatic techniques outside the artist’s conscious control, Magritte pursued a figurative style.” In his words, he wanted to “challenge the real world through a naturalistic and highly detailed depiction of ordinary objects and subjects.” During his time in Paris, Magritte carefully investigated the relationship between text and image, “often breaking apart well-worn connections between the two.” In his iconic The Treachery of Images the painting shows a picture of a pipe, accompanied by the written words “This is not a pipe.” It creates a three-way paradox out of the conventional notion that objects correspond to words and images.

René Magritte: The Treachery of Images

Magritte reimagined painting as a critical tool that could challenge perception and engage the viewer’s mind. His was a method of severing objects from their names, revealing language to be an artifice, full of traps and uncertainties. As art critics have suggested, “the persistent tension Magritte maintained during these years between nature and artifice, truth and fiction, reality and surreality is one of the profound achievements of his art.”

André Souris: Rengaines (Quintette a Vent du Conservatoire du Luxembourg)

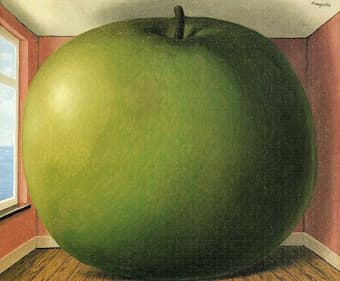

René Magritte: The Listening Room

Magritte strongly believed that music was an ally of surrealism, and he maintained a lifelong interest in music. In fact, the composer André Souris was a close personal friend. Surrealism had a significant following in Brussels, Paris, and New York, and music was seen to possess the direct creative force so eagerly sought by surrealism, as it “surpassed the conventional limitations of speech and illustration and blurred the distinctions between the real and imaginary.” André Breton suggested in an essay entitled Silence Is Golden “that music can be a powerful force for the achievement of incandescence; that music could reveal an inner music of poetic language.” Breton recognized music as “independent of the social and moral obligations that limit spoken and written language.” As a scholar wrote, “The concurrent musical revolutionary impulse was the embrace of an even more counterintuitive approach to writing music. The attack on bourgeois conventions and on the status quo in music took the form of atonality, and the emancipation of dissonance to make audiences uncomfortable.” Various streams of music mirrored a rebellion against “the high-handed modernist conceits of musical modernism, and sought to achieve a revolutionary impact on the audience by permitting the listener an immediate access to the work in a manner comparable to the work of surrealist painters.” It is one of the legacies of Magritte that he sought to engender an active critical sensibility through art, “which ultimately could encourage a craving for unity, peacefulness, freedom, justice and creativity.”

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter

Jake Heggie: A Question of Light, No. 1 “The light of Coincidences (Magritte)” (Nathan Gunn, baritone; Jake Heggie, piano)