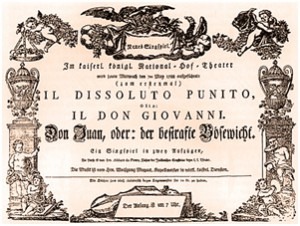

Original playbill for Don Giovani

And much as improvisation is a process, it is a constantly evolving one and a self-fuelling one. Because the moment one has created something, one has something to work with, and to improvise on, generating a new product, which in turn can be improved on etc.. The point is to keep doing it with originality, to keep it in Repetition: to maintain the skills and discipline of preparation, the openness to externalities and the expression of the self throughout this process. Once one has done this a few times, the challenge is to keep up the Repetition, to avoid recollection, which would get one nostalgically stuck and prevent future creation (one can only hope, then, that having done this many more times, the Repetition will become internalised).

That improvisation is such a delicate and subtle art form can has long inspired artists. Kierkegaard and Camus both suggested that theatre players were the perfect conduits of Repetition, since they found meaning and entire existences in the replaying itself. And both these thinkers in turn drew on Mozart and Don Giovani.

Don Giovani, the serial seducer, who is supposed to have achieved Repetition within repetition, is open to many interpretations. On the one hand, one could speculate that he has indeed achieved Repetition and is living his true Self within a context of repetition. On the other, one could guess he was perpetually stuck in Sisyphean recollection mode, compulsively seducing woman after woman in a constantly frustrated pursuit of an ideal: in Albert Cohen’s Belle du Seigneur, when the pretentious Adrien mentions he is writing about Don Giovani, Solal asks if he has added a section on the hero’s ‘inherent contempt of women’ (ironically, Solal himself later gets trapped along with his beloved in a spiral of recollection). Depending on the interpretation one chooses, Don Giovani is either a perfect improviser or a sad caricature of himself. This risk, embodied in the difference between repetition and Repetition, is what makes the character so enticing.

To live one’s life in Repetition, playing. But playing what? Not a pre-written fate, but playing ourselves in a constantly evolving play. More like child’s play then a theatre play. I was fascinated the other day to discover that the commedia dell’arte was originally called commedia all’improviso: this was in contrast to commedia erudita, in which the actors played set parts and delivered lines written by authors. In the commedia all’improvviso, the actors were assigned set roles to play, but the action and the sstory were results of their improvisation. One was a priest, the other a jester, the other a society lady etc.. Initially it seems like there would not be a lot of space for improvisation here: how far could they stray from their characters without seeming unrealistic? Well, as far as they wanted to! That is the point: so long as they did it well, they could stray as far as possible from character, and the public would applaud them. What a lessons for one’s life! Rather than feel constrained by our character, we should embrace our nature and learn to stretch as far as our imagination and our skills can take us.

To live as players, then; not always “in character” but always true to our nature. Funny how commedia all’improviso become dell’arte: at some point someone realised that true art, far from erudition, was the improvisation that happened when characters were let go off. Of the many lessons in which music can teach us about life, improvisation is certainly one of the most difficult and most rewarding ones.

Mozart

Don Giovanni

Overture