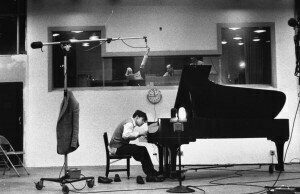

The late great Canadian pianist Glenn Gould made two significant and highly-acclaimed recordings of Bach’s Goldberg Variations, the first in 1955 when he was just 22, the second a quarter of a century later in 1981 when he was nearing the end of his life. Both recordings stand as benchmarks and both offer fascinating insights into the music and Gould’s approach to it. These recordings have never been out of print – a mark of their status and the respect they command in the canon of Bach recordings. The 1955 recording was Gould’s debut disc for Columbia Records and was something of a risk for the record company since at the time the Goldbergs were regarded as one of the obscurities of the repertoire, while the performer was unknown. The 1955 recording is often described as a young man’s recording, full of the exuberance of youth in its extreme tempi and avoidance of some of the repeats. In fact, the swiftness of the playing is partly due to the constraints of the vinyl format and the need to bring the recording within a certain time-frame. No matter: Gould’s Goldbergs became an instant hit, launching both pianist and the work, which entered the standard repertoire of pianists and remains widely performed and recorded to this day.

The late great Canadian pianist Glenn Gould made two significant and highly-acclaimed recordings of Bach’s Goldberg Variations, the first in 1955 when he was just 22, the second a quarter of a century later in 1981 when he was nearing the end of his life. Both recordings stand as benchmarks and both offer fascinating insights into the music and Gould’s approach to it. These recordings have never been out of print – a mark of their status and the respect they command in the canon of Bach recordings. The 1955 recording was Gould’s debut disc for Columbia Records and was something of a risk for the record company since at the time the Goldbergs were regarded as one of the obscurities of the repertoire, while the performer was unknown. The 1955 recording is often described as a young man’s recording, full of the exuberance of youth in its extreme tempi and avoidance of some of the repeats. In fact, the swiftness of the playing is partly due to the constraints of the vinyl format and the need to bring the recording within a certain time-frame. No matter: Gould’s Goldbergs became an instant hit, launching both pianist and the work, which entered the standard repertoire of pianists and remains widely performed and recorded to this day.

Glenn Gould – Aria from Goldberg Variations, 1955 recording

When Gould re-recorded the Goldbergs in 1981, recording technology had advanced considerably (stereo and Dolby surround sound had been invented and digital recording/editing could be used for mainstream recordings). This gave the artist greater flexibility, with the possibility of multiple takes to create a recording with which he was entirely satisfied. Gould had been unhappy with the tempi in the first recording and felt there was no sense of cohesion or narrative flow between the individual variations. The 1981 recording is undoubtedly that of a mature artist: the tempi are thoughtful, almost autumnal, and there is much greater expression throughout the variations. There are elegance and nobility rather than swooning, nervous energy.

Glenn Gould – Aria from Goldberg Variations, 1981 recording

Gould’s two recordings of the Goldberg Variations demonstrate something profound – that two different approaches to the same notes say a great deal about how one ages and how tastes change over time.

The weather changes. The admirable impetuousness of youth usually yields to a more considered view

– John Humphreys, concert pianist

A recording is a snapshot in time, yet preserved forever, unlike a live performance which is a one-off, never to be repeated. Many artists are dissatisfied with their recordings because they know that they never play the same thing in exactly the same way and no sooner has a recording come out, than they wish they had done things differently. As amply demonstrated by Gould’s Goldbergs, the passage of time allows one to reflect on one’s repertoire and how one plays it. One’s perception of the music changes with time and so it makes perfect sense to re-record from a different, more mature perspective.

Other notable “repeat” recordings include Daniel Barenboim’s Beethoven Piano Sonatas. Barenboim was a young man when he recorded his first cycle (between 1966 and 1969), and like Gould’s 1955 Goldbergs, there’s an excitement and spontaneity in these readings. He re-recorded the sonatas for Deustche Grammophon in 1981-84 and two decades later Decca released the audio soundtracks of DB’s live performances of the sonatas (performed and filmed in Berlin’s Staatsoper unter den Linden and issued by EMI on DVD). Like Gould’s Goldbergs, these make for fascinating listening, offering one the opportunity to chart the performer’s artistic and interpretative development and maturity, resulting in new or renewed approaches to the music.

Daniel Barenboim – Beethoven Pathetique Sonata first movement 1967 recording

Daniel Barenboim – Beethoven Pathetique Sonata first movement 1987 recording

That artists choose to re-record works is a mark of how one develops as an artist: one does not and should not stand still artistically. Our responses to our music change with time, experience, growing maturity, and when we return to music we should always find something new within it. For some musicians, capturing the artistic changes that happen across their careers is an important goal and re-recording certain works is a way of marking these changes. In other instances, musicians respond to pressures from a record label: when an artist moves to a new label, they may be encouraged to re-record works to match the success of a previous label.

The best re-recordings don’t recreate, they reinvent. And while listening to them, we try to discover what motivations and inspirations stand behind them.

More Opinion

-

The Predictability of the 2025 Van Cliburn Competition Was Hong Kong's Aristo Sham the 'predictable winner'?

The Predictability of the 2025 Van Cliburn Competition Was Hong Kong's Aristo Sham the 'predictable winner'? -

The Unpredictability of the 2025 Queen Elizabeth Competition Discover why these results have sparked debate among classical music fans

The Unpredictability of the 2025 Queen Elizabeth Competition Discover why these results have sparked debate among classical music fans -

What Makes a Good Concert? A memorable concert requires four essential elements. Find out here

What Makes a Good Concert? A memorable concert requires four essential elements. Find out here -

The Musician’s ‘Non-Negotiables’ Want to level up your music practice? Take inspiration from 'The Bear'

The Musician’s ‘Non-Negotiables’ Want to level up your music practice? Take inspiration from 'The Bear'

Gould’s recordings of Bach’s Goldberg Variations are the benchmark for all subsequent interpretations of this monumental work. Every pianist who comes after Gould benefits from his ground-breaking, sensitive and profound knowledge. Just like there will never be another Bach, alas, there will never be another Glenn Gould.