Tradition is not the worship of ashes, but the preservation of fire

― Gustav Mahler

Bach

Such an attitude can alienate potential concert goers, who fear that they may not “know enough” or are not sufficiently “educated”, to appreciate or enjoy classical music. At concerts, I regularly meet people who are clearly intelligent and culturally aware who enthuse about the music they have just heard and then apologise for “not really knowing enough about it” (the fact that these people can explain the things they liked about the music – details of melody and structure, its emotional impact and the way it transported them to another place – demonstrate to me that they fully appreciate the art form!). And at least those people actually went to the concert; sadly, many are too intimidated by the reverence surrounding classical music to even step inside a concert hall for fear of doing something wrong or appearing ignorant.

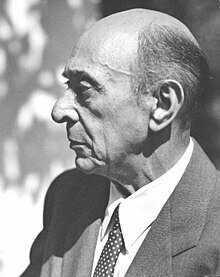

Schoenberg

In concerts, reverence can limit programming: with a bias towards the “great works”, lesser-known composers and music, in particular contemporary music, may be overlooked or excluded, thus denying audiences the opportunity to experience the wilder shores of the repertoire or sample brand new music.

Schoenberg: Gurrelieder – Part I: Orchestral Prelude

Wagner: Tannhauser – Overture

Reverence also breeds prejudice: mention Wagner and you are adored by one group; mention Schoenberg, and you’re disdained by another; mention Minimalism, and another group rolls their eyes. Certain composers are untouchable, beyond criticism, fetishized even – Bach, Mozart, Beethoven, Wagner and Mahler being examples which immediately spring to my mind. Of these, Bach in particular enjoys especial veneration: cycles of Bach’s works are not “performances”, they are “journeys”, “voyages” or “pilgrimages”.

The classical musician’s training is largely still about preserving tradition and the reverential “canonization” of repertoire: we’re taught from a young age that Bach, Mozart, Beethoven, Brahms, Tchaikovsky, Wagner, Mahler…. are the “great” composers. Revering the music in this way can create problems when learning and playing it: for pianists, as for other musicians, certain works – the Goldberg Variations, Beethoven’s last piano sonatas, the great piano concertos, for example – have an elevated status on a par with the works of Aristotle, Shakespeare or Dickens. We hold the music in such awe, carrying the weight of its history, its heritage, the long line of great musicians who have played it, and feel such a tremendous responsibility to these “great works” that our creativity, artistry and personal interpretation may be stifled. The music is imbued with notions of ‘greatness’ even though the player might not actually be feeling it intuitively nor actually believe in it. I’ve experienced it myself, in particular with works by Beethoven and Chopin, and I’ve observed people on piano courses whose reverence towards the music gets in the way of their enjoyment of it.

Respect the music, for sure, but don’t revere it: that prevents us from getting right to the heart of the music and experiencing – and, more importantly, enjoying it – in all its myriad variety.

Bach: Brandenburg Concerto No. 3