Robert Delaunay, 1912

The experimental and visionary paintings of Robert Delaunay (1885-1941) represent a unique fusion of early 20th-century European artistic trends. Visually and intellectually stimulated by the exuberant environment of Belle Epoque Paris, he founded—together with his wife Sonia—a movement termed “Orphism.” The French poet and art critic Guillaume Apollinaire named the movement as he noticed a small number “of painters developing a unique practice, based partially on Cubist theories, but with a focus on vivid contrasting colors and increasingly abstract content.”

Delaunay: Premier Disque, 1913

Similar to the way musicians use notes, Delaunay used color, line and form to create abstract compositions that could inspire emotion. Delaunay writes, “the need for a new subject has inspired the poets, launching them onto a fresh path… Light in nature creates movements in color. The movement is provided by the relationships of uneven measures, of color contrasts among themselves and constitutes Reality.” There was nothing spiritual or magical in his approach to painting, but inspired by the abstract qualities of music, he “scientifically explored different color combination and their psychological effect on human emotion.” Pure abstraction was a way of communicating the deepest aspects of the human experience, as color, according to Delaunay’s vision “was able to express emotions and sensations independent of associations with representational forms.”

Jay Aaron Kernis: Color Wheel (Nashville Symphony Orchestra; Giancarlo Guerrero, cond.)

Delaunay: Self-portrait

Born into upper class Parisian society in 1885, Delaunay initially lived a privileged early life. He was a poor student but showed real interest in painting. As a result he was sent to the atelier Ronsin to study decorative arts in the Belleville district of Paris. “He learned to create large scale theatre sets, which would inform his later stage and mural work.” At the age of 19, Delaunay first exhibited six works at the Salon des Indépendants. He met Henri Rousseau and Jean Metzinger, and according to critics produced “large mosaic-like cubes to construct small but highly symbolic compositions.”

Sonia Delaunay wearing Casa Sonia creations, Madrid, c.1920

In 1909 Delaunay met the passionate artist Sonia Terk, a wealthy Russian émigré who had arrived in Paris to train at the Academy de la Palette. She was married to “the homosexual German art critic and gallery owner Wilhelm Uhde in a marriage of convenience.” Delauney and Terk became lovers, and when she became pregnant she quickly divorced from Uhde. The marriage took place the following year, and over the next 30 years “they formed one of the most remarkable creative partnerships in art history.” They rented an apartment on the Rue des Grands Augustins, and drew inspiration from the vivid colors and patterns they saw in the electric lights on the Boulevard St Michel. Sonia wrote in her diary, “We breathed painting like others lived in alcohol or crime.”

Anton Webern: 5 Pieces for Orchestra, Op. 10 (Cleveland Orchestra; Christoph von Dohnányi, cond.)

Delaunay: Champs de Mars: The Red Tower, 1911

Delaunay: Windows Open Simultaneously 1st Part, 3rd Motif, 1912

Delaunay: Simultaneous Windows on the City, 1912

Delaunay became part of the Parisian avant-garde movement, and he “immersed himself in the world of aesthetic discovery, innovation, and experimentation.” And he developed an increasing fascination with color as a subject in itself. Looking to interpret the modern city through color and rhythm, Delaunay advocated his own theories of color, discussing both color as a material form and its great expressive power. He wrote, “breaking up of form by light creates colored planes… that are the structure of the picture… nature is no longer a subject for description but a pretext.”

Delaunay: Hommage to Blériot, 1914

He would eventually abandon images and realities altogether and turn to complete abstraction. His work was greatly admired by Kandinsky, Macke, and Marc, and Delaunay was invited to contribute at the first “Blaue Reiter” exhibition in Germany in 1912. Apparently, Delaunay was always looking for attention and Gertrude Stein captured his personality when she wrote, “he sees himself as a grand solitary figure when in reality he’s an endless chatterbox who will tell anyone about himself and his significance any time of day or night.” The couple spent the years of WWI in Portugal and Northern Spain, and only returned to Paris in 1920.

Paul Lansky: Word Color (Hannah MacKay, reader; Paul Lansky, computer)

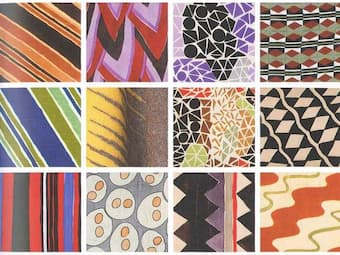

Textiles by Sonia Delaunay

While Sonia had become a highly successful fashion designer who operated 30 some boutiques, Delaunay’s reputation steadily dwindled. After the Wall Street crash in 1929, both artists proudly declared, “We’ll paint and we’ll live like before.” They joined the “Abstract Creation Group” in 1932 and were invited four years later to take part in the Exposition Internationale des Arts et Techniques dans la Vie Moderne.

Bathing Suit designed by

Sonia Delaunay, 1920s

Working with fifty unemployed artists, Delaunay produced huge murals for the aeronautical pavilion. The show was highly successful, but overshadowed by “the overwhelming success of Picasso’s Guernica in the same show.” The couple made plans to travel to New York, but fled to the South of France to avoid the Nazi invasion. Suffering from cancer, Robert’s health deteriorated and he died in Montpellier in 1941. Just four years after his death, Delaunay’s name was virtually unknown. His reputation, primarily based on his activity before WWI, however, is seen “as fundamental in the evolution of abstract art theory.”

Delaunay: Tour Eiffel, 1926

Delaunay: Circular Forms, 1930

Delaunay: Rhythms, 1934

Delaunay: Rythme n°1, décoration pour le Salon des Tuileries, 1938

Sonia Delaunay: Rhythm Colour no. 1076, 1939

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter

Alban Berg: Lyric Suite (Alban Berg Quartet)