For a number of commentators, the pianist Samuil Feinberg (1890-1962) was considered a bridge, the most important link, “between the two distinct factions of the celebrated Russian school of pianism, which pitted Scriabin’s mystical, sexual, opiate music against Prokofiev’s dynamism and percussive approach to composition. Feinberg was the pianist both composers admired above all.”

Samuil Feinberg

As a composer, Feinberg’s initial style essentially was a reflection of Scriabin, and an engagement with his “intense chromatic writing and thick textures.” A scholar writes, “Feinberg’s art is darker than Scriabin’s, and there is not that striving toward the light; neither is there a declared program of any kind because Feinberg preferred to leave such matters to the imagination of the listener. Like Scriabin, Feinberg used the full sweep of the keyboard, but he tended to arrive at his complex web of textures by polyphony, not as Scriabin, by harmony.”

Samuil Feinberg: Piano Sonata No. 1, Op. 1 (Nikolaos Samaltanos, piano)

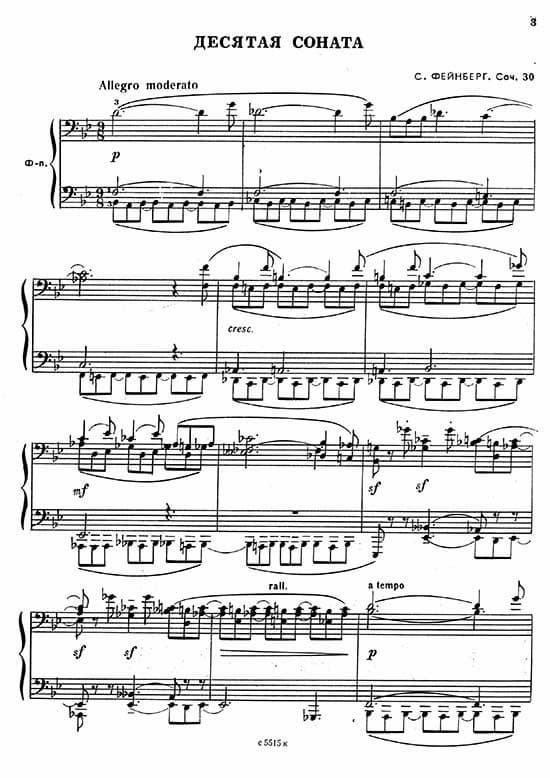

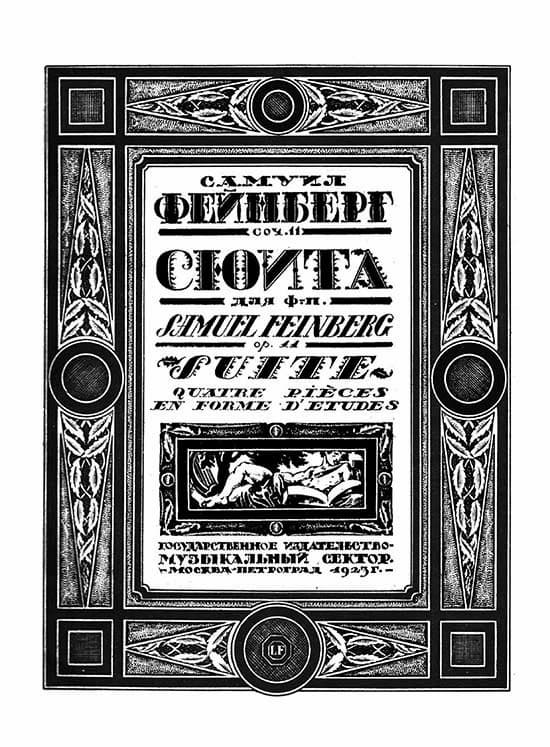

As a composer, Feinberg has unjustly fallen into oblivion. The vast majority of his compositions are for solo pianos and include 12 Sonatas, three piano concertos, two fantasias, two suites, two romances, and organ transcriptions. He also wrote “Classical Period” cadenzas and various transcriptions, including fifteen re-workings of compositions by Bach and others. In his piano sonatas, Feinberg adhered to a one-movement model and the superimposition of rhythms in different registers of the keyboard. His first sonata is described as “Scriabineque in style with extreme virtuosity, long extended harmonic motions, reliance on sequences, and an expressionist style.” The musicologist Leonid Sabaneyeff explained, “First, Feinberg is chiefly a composer of harmonies and rhythms. He is almost no melodist at all. Musical fabric is bizarrely wavering and turbulent. These compositions are some sort of tonal tempests and whirlwinds, not music. He is a composer who recognizes virtually no slow tempo. His visions are dynamic and madly precipitous recalling the hallucinations of a sick man. The destruction of the rhythmic web and substance occasionally frightens the auditor with its abnormality.”

Samuil Feinberg: 4 Preludes, Op. 8 (Jenny Lin, piano)

Samuil Feinberg’s Sonata No. 10, Op. 30

During his conservatory years, Feinberg was scheduled to take counterpoint studies with Sergei Taneyev. However, Feinberg was apparently not willing to show his attempts at composition to his prospective teacher, “who was known to be very conservative.” Instead, he took private lessons in composition with Nikolai Zhilyaev, a close friend of Scriabin and student of Taneyev. Feinberg composed his first songs, however, his career as a composer got started in earnest when he was discharged from military service in 1915. A scholar retrospectively wrote in 1927, “At that time, Feinberg embarked upon composition as a completely mature and distinctive personality, fully conscious of himself and of his creative ideals, which hitherto had not been completely clear to him.” According to scholars, “Feinberg and Scriabin shared a central compositional tenet in their desire to go well beyond previously set limits to express that which has not yet found its voice but is longing to do so.”

Samuil Feinberg: Piano Sonata No. 6, Op. 13 (Hideyo Harada, piano)

Feinberg’s Sixth Sonata has been described as probably his finest work. Composed in 1923, it was selected for performance at the International Society for Contemporary Music Festival in Venice in 1925. The work provides an entire encyclopedia of references, from the bell-like opening reminiscent of Debussy, to the influences of Janáček and Schoenberg clothed in a romantic feel that searches for the harmonic language of Liszt and Rachmaninoff. There is no sense of continual evolution, but “the composer seems to find himself on the tip of an apocalyptic sword, and the listener remains imprisoned by the spirit of confusion and even of irreparable tragedy that dominates this work.” While often dark and violent, the work does contain passages of great luminosity. A contemporary writer stated, “The grotesque and nightmarish world in the 6th Sonata is the exact reflection of our era of wars and revolutions… in the unhealthy and delicate psyche of a great artist.”

Samuil Feinberg: Suite No. 2, Op. 22 (Hideyo Harada, piano)

Samuil Feinberg’s Piano Concerto No. 2

Feinberg composed the majority of works during the 1920s, during a period of membership at “The Association for Contemporary Music.” Feinberg experimented with a virtuoso style that was, however, never divorced from artistic considerations. As Feinberg writes in his Pianism as Art, “Sometimes the most prosaic attempts lead to unexpected artistic discoveries, while an inspired breakthrough requires long, unrelenting work for triumphal practical results. Everything in the work of an artist is important and illuminated by the grand aesthetic goal. It is hard to distinguish in art between carefully worked out techniques, which form the daily labor of an artist, and the rarer, enlightening, and intuitively found paths and solutions. There are no accomplishments that have not been preceded by many steps in developing mastery and an understanding of the principles of the creative method. It is commonly objected that the path of a creative artist is different from the usual conscious behavior of man that it is built of unconscious, intuitive acts, like the path of a lawless comet in the predictable circle of planets. However, much can be accounted for in the domain of artistic instinct; a constant, stable logic of artistic interactions can be found, just as a comet’s orbit can be marked on a map of the stars.”

Samuil Feinberg: Piano Concerto No. 2, Op. 36

During the 1920s, Feinberg was considered one of the more exciting of the new talents. He was considered similar to Schumann, Poe, and Dostoevsky as “possessing an obsessed personality as a composer… His works, in general, tend to the Scriabinesque one-movement model, and cohesion is constantly enhanced by building passage work from thematic materials.” Feinberg was very much in line with contemporary composers “who are seized by an artistic vision and tend to follow it for the rest of their productive lives, to the exclusion of external practicalities.”

Samuil Feinberg’s Suite

However, things decidedly changed in 1929 when Feinberg’s composition teacher Nikolai Zhiliayev was jailed by the state-sponsored terrorism of Joseph Stalin. For one, Feinberg was no longer allowed to leave Russia except for serving as a competition jury member in 1936 and 1938. And he began to develop an entirely different compositional style during this time. His style of composition became more conservative, “preserving his sensitivity of expression and continuously displaying his fondness for contrapuntal technique.”

Samuil Feinberg: Violin Sonata No. 2, Op. 46 (Ilona Then-Bergh, violin; Michael Schäfer, piano)

During his initial foray into composition, Feinberg had taken his primary inspiration from Scriabin, but in his second compositional style, he pursued stimulation garnered from Prokofiev. Feinberg’s compositions after 1936 display greater simplicity, diatonic inspired harmonies, and a greater emphasis on melody. It resulted in a style that was now influenced by folk music.

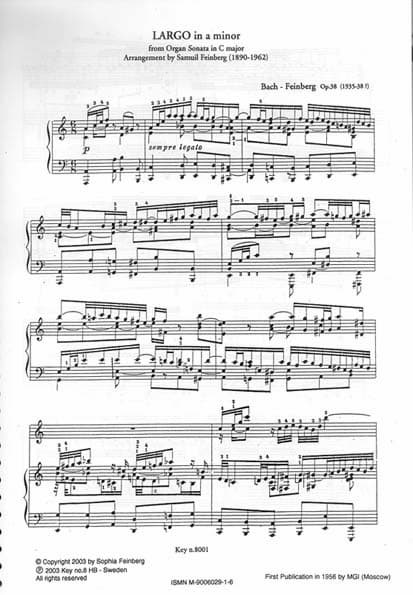

Samuil Feinberg’s Bach transcription, “Largo”

A scholar writes, “His interest in folk music was essential for a composer to survive the Soviet regime, and as his career gradually moved away from composition toward teaching and performance, it was certainly less dangerous in those spheres of activity.” It has also been suggested, “that Feinberg treated folk melodies in the same far-flung matter as he did his own original melodic lines, but the overall result became listless and spiritless, presumably because he was not manipulating his own highly charged material.” I could not disagree more, as the intimacy and aim for greater simplicity produced a translucent clarity in his 3 Songs for Piano, composed in the late 1930s.

Samuil Feinberg: 3 Songs for Piano, Op. 27a

Feinberg held a life-long admiration for the music of Johann Sebastian Bach. As a performer, he played and recorded the Well-Tempered Clavier, and as a composer, he fashioned a number of Bach transcriptions. As he explains, “transcriptions are the composer’s desire to participate in the realization of the original intentions… A noteworthy performer who has devoted his life to working on perfect realizations of the ideas of various composers has spent many hours on practice and technique, and has penetrated special mysteries that have been opened only to him.” As such, Feinberg created elegant and sleek keyboard transcriptions that forego Lisztian extremes of texture and doubling to achieve a more intimate chamber style. Feinberg always stays deeply respectful of the original, “but his re-workings are infused with genius and inspiration.”

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter

Superb