Bernhard Romberg

Cello playing techniques were established in tandem with the development of the instrument—its shape and size changed; the metal spike or endpin inserted into the bottom of the cello to hold the instrument was adopted; cellists ventured out of the first or lowest positions into the high registers requiring new fingering approaches. As the cello’s role became more expanded, beyond simply a bass instrument, and transformed into a virtuosic solo instrument, methods became systematized.

The German Schools

Two schools of cello playing were founded in Germany, one in Bonn, by Bernhard Romberg (1767-1841), and the other by Friedrich Dotzauer (1783-1860) founder of the Dresden school.

Romberg: Divertimento from Austrian Folksongs, Op. 46 for cello and guitar

Romberg, an outstanding performer, is responsible for simplifying cello notation. At the time, composers like Boccherini sometimes wrote cello parts in five different clefs. Beethoven and Mozart, when they wrote for cello in the treble clef, penned the music an octave higher than it was to sound. Even in my generation publishers had not yet modified this practice making reading music unnecessarily complicated for cellists! Romberg simplified notation limiting cello music to three clefs—the bass, tenor, and treble clef (sounding where it was written.) Romberg also introduced a longer fingerboard, with a longer neck on the instrument, allowing cellists to venture into higher positions by using the thumb. He established the notation for the thumb, a circle with a small line. (see the diagram) and also modified the C string side of the cello so it could resonate more.

Romberg, an outstanding performer, is responsible for simplifying cello notation. At the time, composers like Boccherini sometimes wrote cello parts in five different clefs. Beethoven and Mozart, when they wrote for cello in the treble clef, penned the music an octave higher than it was to sound. Even in my generation publishers had not yet modified this practice making reading music unnecessarily complicated for cellists! Romberg simplified notation limiting cello music to three clefs—the bass, tenor, and treble clef (sounding where it was written.) Romberg also introduced a longer fingerboard, with a longer neck on the instrument, allowing cellists to venture into higher positions by using the thumb. He established the notation for the thumb, a circle with a small line. (see the diagram) and also modified the C string side of the cello so it could resonate more. Romberg: Cello Sonata E minor mvt 1 Allegro non troppo

Meanwhile, the Dresden court attracted some of the finest musicians, including Dotzauer. Although Dotzauer still played without an endpin, he was the first to advocate holding the bow closer to the frog—the ebony end of the stick. This afforded more control of the right hand and production of sound. He also advocated limiting the use of vibrato. The beauty and purity of tone became paramount.

Bernhard Cossmann

Both of the German schools prompted a greater knowledge of the fingerboard, and more solid, and precise playing. Nobility, composure, and seriousness was the hallmark of German cello playing. History has not treated Romberg well due to a terrible faux-pas! Beethoven admired Romberg and offered to write a cello concerto for him. The cellist was nonplussed. He didn’t know how to tell Beethoven that he found the composer’s music beyond comprehension. Romberg declined, telling Beethoven he preferred to perform his own compositions.

When a conservatory opened in Dresden the logical heir apparent, Dotzauer’s student, Friedrich August Kummer (1797-1879) took the position. Acclaimed as a performer, he was known for his powerful tone and simple, natural playing. Another German cello school proponent, Friedrich Grützmacher, who studied with a pupil of Dotzauer became principal cello of the Leipzig Gewandhaus and professor in Leipzig. These cellists wrote many works for cello, including concerti, lovely duos, and pieces, in addition to their method books. Against excessive vibrato and unwarranted rubato, (rhythmic freedom), Kummer and Grützmacher, sustained the objective, intellectual, and elegiac German approach.

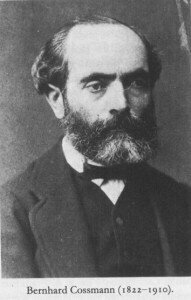

Two of Kummer’s more famous students were Bernhard Cossmann (1822-1910) and Julius Golterman (1825-1876). Cossmann, one of the founders of the Frankfurt Conservatory, was a brilliant soloist and prolific composer of fantasias as well as cello education works such as Studies for Developing Agility for Cello. The lineage gets even more interesting as we see how the German school influenced the entirety of Europe.

Julius Klengel: Cello Concerto No. 1 in A Minor, Op. 4

David Popper

Romberg |

|

↓ |

|

Dotzauer → → | Grützmacher |

↓ | ↓ ↓ |

Kummer | Klengel Becker |

↓ | ↓ ↓ |

Golterman | ↓ Mainardi, Harrison, Grümmer |

↓ |

|

Popper |

|

↓ |

|

Schiffler | Aronson, Feuermann, Piatigorsky, Suggia, Pleeth |

↓ |

|

Starker |

|

The brilliant precision, strict teaching, and noble approach of the German school is evidenced in all of these wonderful cellists.

Next, we will examine the French and Russian schools of cello playing—is also represented by a long line of great cellists whose influence is felt today.

Kummer Duo for two cellos Op.156 Nº5 Finale. Allegro. La Hispaniola