Robert Schumann

Robert Schumann (1810-1856) was a seminal figure in 19th-century musical and critical thought. He was a visionary composer and seasoned journalist, a cultured man of letters and a musical genius who eventually succumbed to mental illness. An individual of incredible facility and complexity, Schumann has been studied from many possible angles. Scholars and critics have explored his inspirations and musical and literary sources alongside sociological and psychological motives within his specific cultural and artistic background.

Ludwig Rellstab

Throughout Schumann’s life he was surrounded by a vast number of highly talented and interesting people, and in this little series we will meet some of these individuals. Ludwig Rellstab (1799-1860) was a German poet and music critic. Franz Schubert and Franz Liszt set his poetry, and he is known for attaching the nickname “Moonlight Sonata” to Beethoven’s Sonata No. 14 in C-sharp minor. Rellstab also wielded considerable influence as a music critic, and he favorably reviewed Schumann’s compositions from time to time. In his Abegg Variations Op. 1, Schumann announced himself to the world as a virtuoso pianist-composer, a fact clearly recognized by Rellstab in his 1832 review.

Robert Schumann: Abegg Variations, Op. 1 (Idil Biret, piano)

Ignaz Moscheles

Robert Schumann began to compose before the age of seven, and a biographical sketch relates “Schumann, as a child, possessed rare taste and talent for portraying feelings and characteristic traits in melody; he could sketch the different dispositions of his intimate friends by certain figures and passages on the piano so exactly and comically that everyone burst into loud laughter at the similitude of the portrait.” That love and aptitude for music fiercely competed with his love and talent for literature. One of the reasons why music eventually won the day can be attributed to the Bohemian pianist and composer Ignaz Moscheles (1794-1870). Schumann was only six years old when his mother took him to the town of Carlsbad to hear a performance by one of the most impressive piano virtuosos of his time. Robert was thunderstruck, and he carefully preserved the concert program for the next twenty years. In the event, Robert decided to follow into Moscheles’ footsteps and become a piano virtuoso himself. Eventually, Moscheles became good friends with Robert and Clara Schumann, and Schumann dedicated his “concerto without orchestra,” the Piano Sonata No. 3 in F minor Op. 14 to his friend in 1836.

Robert Schumann: Piano Sonata No. 3 in F minor Op. 14

William Sterndale Bennett

Robert Schumann shared a special kinship with William Sterndale Bennett (1816-1875), whom he described as “a most brilliant artist.” Bennett made several journeys to Germany, including extended visits to Leipzig where he met with Mendelssohn and Schumann. Bennett wrote in a letter, “Mendelssohn took me to his house and gave me the printed score of his overture “Melusina,” and afterwards we supped at the Hôtel de Bavière where all the musical clique feed … The party consisted of Mendelssohn, Ferdinand David, and a Mr. Schumann, a musical editor, who expected to see me a fat man with large black whiskers.” Bennett’s relationship with Mendelssohn remained formal, but his friendship with Schumann was genuine. They went on long country walks by day and went drinking at the local taverns by night. And they dedicated substantial compositions to each other; Bennett inscribed his Fantasie pour le piano forte Op. 16 to Schumann, and Schumann reciprocated with his Symphonic Etudes, op. 13. Robert was invited to England, but the trip never took place. As such, it was left to his wife Clara to perform in the 1856 opening concert in London under the baton of Bennett.

Robert Schumann: Symphonic Etudes, Op. 13

Ernestine von Fricken

When Robert Schumann met Ernestine von Fricken in 1834, he fell head over heels in love with her. Ernestine was a gifted pianist and lodged with her piano teacher Friedrich Wieck, as did Robert Schumann. There has been the suggestion that Papa Wieck encouraged the intimacies between Ernestine and Schumann, since “he saw how much they distressed Clara whom he wished to protect.” In the event, Robert and Ernestine got engaged, and Baron von Fricken agreed to the marriage and decided to adopt Ernestine, as she was probably the illegitimate child of his sister. That adoption would legitimize her, but regrettably, it did not improve her economic conditions. We are not sure why the engagement was suddenly dissolved in the summer of 1835, but Schumann’s unexpected declaration of love for Clara might have had something to do with it. Fact is that Schumann dedicated a number of works to Ernestine who might have given him syphilis in return. Ernestine married Count Zedtwitz in 1838, but she and her adoptive father rejected to support Friedrich Wieck in the court case against Robert Schumann.

Robert Schumann: 3 Gesänge, Op. 31 (excerpts) (Anne Sofie von Otter, mezzo-soprano; Bengt Forsberg, piano)

Anna Maria Leopoldine Blahetka

Anna Maria Leopoldine Blahetka (1809-1885) was a celebrated child prodigy, who studied piano with the likes of Joseph Czerny, Friedrich Kalkbrenner, Ignaz Moscheles and Katharina Cibbini. She first performed publically at the age of seven, and the Viennese press immediately declared her a “genius.” By the age of eleven, and under the guidance of Vienna’s most revered teacher Simon Sechter, she issued her first compositions. Leopoldine subsequently embarked on a number of concert tours throughout Europe. In 1825/26, she performed in Germany and Robert Schumann saw her at a concert. He was greatly impressed by her technical prowess and execution—a feature that would also astound Niccolò Paganini—and by her compositions. He described her works as “truly feminine, delicate, considerate and elaborate.” Robert had to be somewhat careful with his unreserved praise of Leopoldine, as she was a direct competitor to Clara Wieck who was just starting her own career.

Leopoldine Blahetka: Variations for Flute and Piano, op. 39

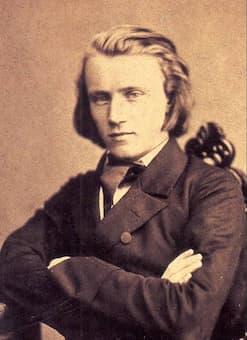

Johannes Brahms

Johannes Brahms was barely 20 years of age when he first visited the Rhineland in 1853. He made friends with Joseph Joachim in Göttingen, and he first personally met Robert and Clara Schumann in Düsseldorf in September 1853. Brahms arrived unannounced carrying a letter of introduction from Joachim, but since Schumann was not at home, they first met the next day, on 30 September. As we all know, it was an encounter of far-reaching personal and musical consequences, as Brahms stayed with the Schumann’s for several weeks and became a close family friend. Schumann published his article “New Paths,” hailing the arrival of the “new Messiah,” and together with his student Albert Dietrich and with Brahms, Schumann collaborated on the composition of the F-A-E Sonata. Designed as a gift and tribute to Joseph Joachim, the three composers encoded Joachim’s motto “Frei aber einsam’ (Free but lonely), and all four movements are based on the musical notes F-A-E. But time was short, as Schumann was admitted to the asylum at Endenich on 29 July 1856 at the age of 46. Brahms visited his friend and hero on multiple occasions, and there was a persistent rumour that Clara and Johannes destroyed a good many of Schumann’s late works following his death, deeming them tainted by his madness.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter

Schumann/Brahms/Dietrich: F-A-E Sonata