Robert Schumann and Clara Wieck © pages.stolaf.edu

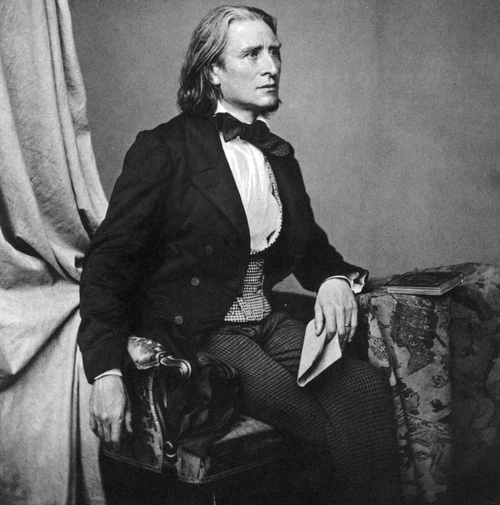

Marked by its technical bravura, Widmung (or Dedication in English) has remained one of the most popular encore pieces in piano recital, allowing pianists to display their virtuosity. However, Widmung is much more than a mere showpiece – containing probably the most passionate music writing and most heartfelt feelings. Written by Robert Schumann in 1840 (this piece was from a set of Lieder called Myrthen, Op.25), this piece was later arranged for piano solo by Franz Liszt. Myrthen was dedicated to Clara Wieck as a wedding gift, as he finally married Clara in September, despite the opposition from Clara’s father (who was also Robert’s piano teacher).

Below is the text of Widmung, written by Friedrich Rückert, with English translation:

Original Text by Friedrich Rückert | English Translation (by Richard Stokes, author of The Book of Lieder (Faber, 2005)) |

Du meine Seele, du mein Herz, | You my soul, you my heart, |

The work starts with a flowing sense of pulse, while the first phrase (“Du meine Seele, du mein Herz”) already captures Schumann’s love for Clara and devotion to the relationship. Here, Schumann sincerely confesses to Clara, declaring how important she is to him. For him, Clara is his angel, his spiritual support, and his entire world. Nevertheless, there is still a sense of fear and insecurity in the music, due to separation and uncertainty about their future. This complex mixture of feelings, as a true and full-bodied representation of love, certainly strengthens the emotional power of the music.

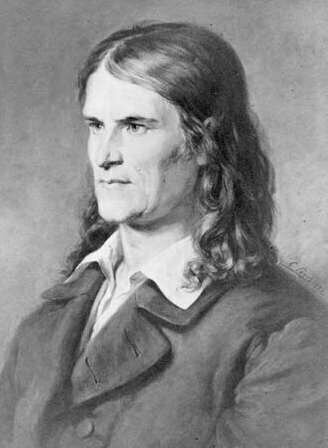

Friedrich Rückert © www.britannica.com

Liszt lengthened the first section by repeating the first theme, but with the melodic line mostly embedded in left hand (with some intertwining) and accompaniment in higher register. Then, the music moves on to the chordal section in E major, which is unchanged in Liszt’s arrangement. The repeated chords convey warmth, tenderness and peace, especially when the text here is associated with death and heaven. Here, the love has changed into everlasting, eternal one – love that transcends space and time.

Franz Liszt © img.wikicharlie.cl

After the brief hand-crossing passage, the music reaches its most technically brilliant and rousing part with arpeggios on right hand and chords highlighting the melodic line on left hand, revealing Schumann’s most intimate feelings. It is the moment when Schumann’s love for Clara becomes so dramatic and uncontrollable, and eventually erupts – a perfect combination of rapture, passion, commitment and sense of elevation. The rich orchestral colours (such as the harp-like figurations, quasi-brass calls) in the music further heightens the emotional intensity. What an outpouring of love here.

In the extended coda, where there are some triumphant chords marked fff, the passion in the music remains, but this time presenting different moods. With ecstatic joy, the music transforms into a declaration, as if Schumann is announcing that he is determined to spend the rest of his lifetime with Clara and willing to make sacrifices in the face of adversity, for Clara is an indescribable miracle of his life.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up for our E-Newsletter

One small mistake in your translation:

“Schwebe” means “float”—“strebe” would be “aspire”.

AND although I understand why Mr. Stokes chose “guardian angel” for “guter Geist”,

there IS a proper word in German for this: “Schutzengel”. And this man is a lecturer

on German song?

How can anyone discuss this Lied without acknowledging the quotation in the piano coda of Schubert’s Ave Maria? As if Ruckert’s poem is not praise enough for the object of devotion, Schumann one-ups Ruckert by comparing Clara to St. Mary!

I knew the postlude was pensive and warm but managed not to catch the close similarity to the Schubert theme. Thanks for pointing it out. At another place in his songs, “Im Rhein, im heiligen Strome,” Schumann, setting Heine, also compares his loved one to the Virgin, this time in explicit terms. But if the music at that point alludes to a theme in his own or some other composer’s work, I don’t recognize it.

I appreciate that Liszt composed his “paraphrase” of Schumann’s Widmung … but I’ve been unable to learn WHEN Liszt composed his “paraphrase” 😄!

Can you provide any help on this point?

Thanks. Brian