Sergei Rachmaninoff, 1897

Sergei Rachmaninoff (1873-1943) was one of the last great pianist-composers in a long tradition stretching back to Mozart, Beethoven, Liszt and Brahms. He always maintained that “a composer’s music should express the country of his birth, his love affairs, his religion, the books which have influence him, and the pictures he loves… My music is the product of my temperament…”

Medtner and Rachmaninoff

Fiercely egotistic in artistic matters, Rachmaninoff frequently experienced great spiritual anguish, often without any specific cause. However, his longing with nothing to long for should be considered philosophical melancholy rather than morbidity. Very few people ever heard him laugh, and only occasionally did he crack a rare smile. Although he was often grave in expression and mannerism, he also disclosed a healthy cynicism and wry humor. Rachmaninoff might also have mentioned that his music owned a great deal to a circle of esteemed colleagues, famous contemporaries, and close friends.

Rachmaninoff and Medtner with wives 1938

He certainly shared a warm and respectful friendship with fellow composer Nikolai Medtner (1880-1951), whom he pronounced “the greatest composer of our time.” Their close friendship is embodied in two piano concertos dedicated to one another. Medtner dedicated his Second Piano Concerto Op. 50 to Rachmaninoff, while Rachmaninoff dedicated his Fourth Piano Concerto to Medtner.

Sergei Rachmaninoff: Piano Concerto No. 4, Op. 40 (Arturo Benedetti Michelangeli, piano; Philharmonia Orchestra; Ettore Gracis, cond.)

Rachmaninoff’s public utterings should always be taken with a grain of salt. Frequently, the painfully private composer would hide away the true sources of his inspirations from the prying public. Such is the case with his first large-scale orchestral work Der Fels (The Rock). Composed shortly after receiving a Gold Medal for his opera Aleko, the 19-year-old-composer set his sights on a distinctive symphonic poem. The published first edition included the following lines of the poem “The Rock” by Michael Lermontov:

The golden cloud slept through the night

Upon the breast of the giant rock,

Floated happily away early in the morning

Across the sea to the blue far-away sky.

But a sheen of it remained

In the ruts of the rock, moist as the tears,

Which the old one, now alone, full of longing

Is crying for those who the wind has blown away.

Anton Chekhov

Everyone assumed that the work was a musical response to that poem, but the true inspiration is revealed in a letter Rachmaninoff wrote to his literary hero Anton Chekhov (1860-1904) in 1898. “To my dear and highly esteemed Anton Pavlovich Chekhov, the author of the story “On the Road,” which served as the programmatic basis of this composition.” As such, it was actually Chekov’s story—which was also prefaced by Lermontov’s poem—that provided the impetus. A middle-aged man meets a young woman and tells her about his love and his search for happiness and success. However, like the clouds drifting away in the wind, the woman quietly goes away the very next morning.

Sergei Rachmaninoff: The Rock, Op. 7 (Royal Liverpool Philharmonic Orchestra; Vasily Petrenko, cond.)

Alexander Siloti and Franz Liszt

Alexander Siloti (1863-1945) studied piano at the Moscow Conservatory with Nikolai Zverev and Nicholas Rubinstein. He also studied composition with Tchaikovsky, and counterpoint and theory with Taneyev. Upon graduation, Siloti traveled to Weimar and became a student of Franz Liszt between 1883 and 1886. He quickly became Liszt’s favorite student, who vigorously promoted his growing career as a pianist. Once Siloti returned to the Moscow Conservatory in 1887, he became a sought-after pedagogue and taught, among many others, his younger cousin Sergei Rachmaninoff. Over many decades, Siloti served Rachmaninoff not only as a teacher, but also as a mentor and sponsor.

Siloti and Rachmaninoff

When Rachmaninoff fell critically ill with brain fever in 1891, Siloti paid all the medical expenses, prompting Rachmaninoff to call Siloti “my life savior.” And he initially dedicated his unfinished string quartet, the Ten Piano Preludes, Op. 23 and his first Piano Concerto to Siloti. Their relationship might have slightly soured in the end, but they always had perfect musical trust in each other.

Sergei Rachmaninoff: Ten Preludes, Op. 23 (Boris Giltburg, piano)

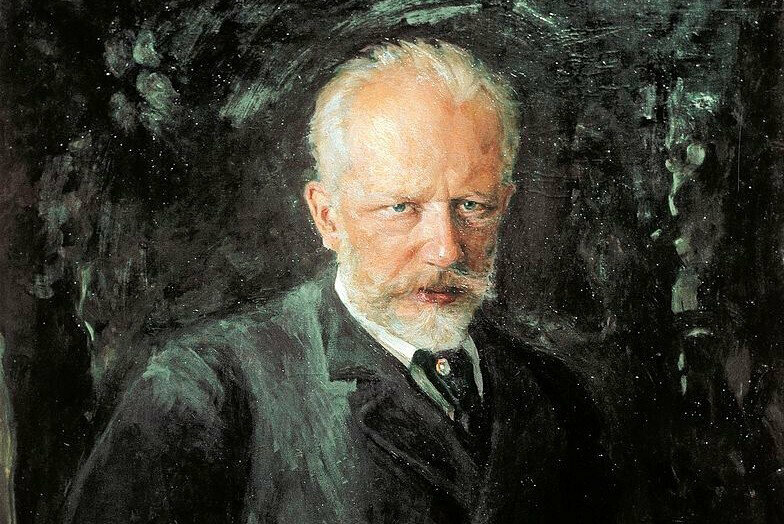

Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky

Sergei Rachmaninoff first met Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky at a musical soiree organized by his teacher Nikolay Zverev. Apparently Tchaikovsky “predicted a great future” for the 16-year-old Rachmaninoff and he engaged him to make a four-hand arrangement of his ballet The Sleeping Beauty. In the event, Tchaikovsky did not like the Rachmaninoff’s arrangement as it “was absolutely lacking in courage, initiative and creativity.” Regardless, Tchaikovsky continued to support and praise Rachmaninoff’s compositions during his years at the Moscow Conservatory and beyond. When Tchaikovsky visited Moscow in 1893, Rachmaninoff presented him with an inscribed copy of his Morceaux de Fantaisie, Op. 3. And when Rachmaninoff focused on the staging of his one-act opera Aleko, Tchaikovsky heartily endorsed the project. Tchaikovsky even suggested that Aleko should be performed together with his Iolanta as a double-bill at the Bolshoi, but his untimely death on 25 October put an end to these plans. Tchaikovsky’s death prompted Rachmaninoff to compose a piano trio dedicated to the memory of “Russia’s most beloved composer.” The Trio élégiaque No. 2 in D minor, Op. 9, was completed on 15 December 1893. In 1930 Rachmaninoff recalled the generous encouragement he had received from Tchaikovsky and paid tribute to his character. “Of all the people and artists whom I have had occasion to meet, Tchaikovsky was the most enchanting. His delicacy of spirit was unique. He was modest like all truly great men and simple as only very few are. Of all those I have known, only Chekhov was like him.”

Sergei Rachmaninoff: Trio élégiaque No. 2 in D minor, Op. 9 (Beaux Arts Trio)

Sergei Taneyev

Rachmaninoff’s First Symphony was premiered in March 1897 and prompted a scathing review from the critic César Cui. “If there were a conservatory in Hell, and if one of its talented students were to compose a programme symphony based on the story of the Ten Plagues of Egypt, and if he were to compose a symphony like Mr. Rachmaninoff’s, then he would have fulfilled his task brilliantly and would delight Hell’s inhabitants.” And when Rachmaninoff asked the composer Sergei Taneyev for his assessment of the work, he got the following response, “These melodies are flabby, colorless—there is nothing that can be done with them.” Given such devastating assessments it is hardly surprising that Rachmaninoff fell into a deeply depressive state which lasted for the better part of three years.

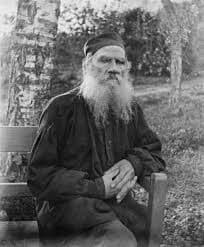

Leo Tolstoy

To make matters worse, Rachmaninoff and his good friend the great singer Fyodor Chaliapin visited the Russian author Leo Tolstoy, one of Rachmaninoff’s literary heroes. Music had always been an enormous influence on Tolstoy, and it “penetrated the deepest recesses of his soul, it stirred his whole being, it released in him embryonic thoughts and emotions of which he himself was not cognizant.” And above else, he abhorred anything artificial, writing “Art is not art if it is invented. It must be natural and sincere,” he exclaimed. Apparently the elderly Tolstoy listened patiently to Rachmaninoff’s music and eventually asked, “Tell me, does anyone want this type of music?” As we all know, it took extended sessions of hypnotherapy to save and restore Rachmaninoff’s self-esteem.

Sergei Rachmaninoff: 12 Songs, Op. 14 (Joan Rodgers, soprano; Annamaria Popescu, mezzo-soprano; Alexandre Naoumenko, tenor; Sergey Leiferkus, bass; Howard Shelley, piano)

Rachmaninoff, Walt Disney and Horowitz

Did you know that Mickey Mouse was one of Rachmaninoff’s best friends? It all started when Sergei Prokofiev met Walt Disney in 1938, after seeing the film Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs. As he wrote to his family back in Russia, “…Most American films are made in Hollywood and they build whole houses, castles and even cities of cardboard for them… I have also been to the house of Mickey Mouse’s papa, that is, the man who first thought up the idea of sketching him.” Well, Rachmaninoff would better this in 1942 when he met Mickey Mouse in performance! Together with Vladimir Horowitz, Rachmaninoff went on a tour of the Walt Disney studios and was treated to one of Disney’s early short animations called The Opry House of 1929. It features Mickey Mouse as the soloist in, among others, Rachmaninoff’s famous C-sharp minor Prelude. Because of its overbearing popularity, Rachmaninoff had come to detest this particular piece. However, he had nothing but praise for Mickey Mouse’s performance. “I have heard my inescapable piece done marvelously by some of the best pianists, and murdered cruelly by amateurs,” he remarked, “but never was I more stirred than by the performance of the great maestro Mouse.”

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter

Sergei Rachmaninoff/Mickey Mouse: The Opry House, (excerps Prelude in C-sharp minor)

Apart from Chaliapin, Enrico Caruso and Fritz Kreisler often visited with Sergei

Other than at receptions and green room interactions (none of which are documented), Rachmaninoff and Caruso were together socially only once, a New Year’s eve dinner in Atlantic City NJ. This wasn’t a friendship in the sense of his with Hofmann, Kreisler, Horowitz, Medtner & the Lhevinnes.

What about the Marx brothers?