“Music is enough for a lifetime, but a lifetime is not enough for music”

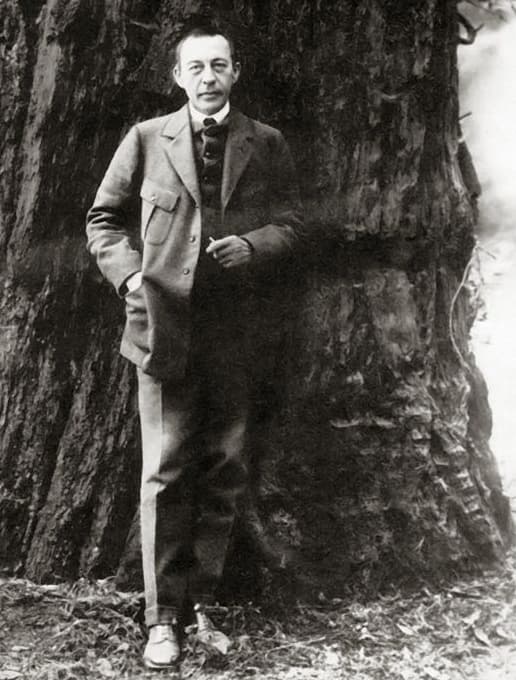

Rachmaninoff in California, 1919

On 28 March 2023 we commemorate the 80th anniversary of Sergei Rachmaninoff’s death. After a concert career as a pianist that lasted fifty years, Sergei Rachmaninoff (1873-1943) decided that the 1942–3 Season would be his last. Every year since his arrival in the USA he had undertaken exhausting tours, and recently had been suffering from lumbago, arthritis and extreme fatigue. Nearing his seventieth birthday, Rachmaninoff bought a house in Beverly Hills, and planned to retire to his new home in California. Rachmaninoff complained to a friend in the autumn of 1942, “that in general, I’m not lucky with houses.” In fact, he had been forced to abandon five of the six homes he had owned, the first falling victim to the 1917 Russian Revolution. Rachmaninoff wrote, “It’s true, I’ve bought a house. A small, neat house on a good residential street in Beverly Hills. It has a tiny garden with lots of flowers and several trees: an orange tree, a lemon, and a nectarine.”

Sergei Rachmaninoff: Rhapsody on a Theme of Paganini, Op. 43

A statue remembering Rachmaninoff’s last concert

In the months before the Elm Drive house was ready to move into, Rachmaninoff drove down from his Tower Road estate with a shovel and a rake, “spending his days digging and making plans for his garden and planting a row of trees in the front yard for privacy.” Apparently, the home held two Steinway pianos, “which he played together with Vladimir Horowitz and other guests.” However, while on tour in January 1943, Rachmaninoff was clearly unwell, and he continued to complain of persistent cough and back pain. A doctor diagnosed him with pleurisy and advised that a warmer climate would aid in his recovery. Rachmaninoff, however, insisted that the tour should continue. He last appeared as a concert soloist in Beethoven’s First Piano Concerto and his Rhapsody on a Theme of Paganini on 11 and 12 February 1943 with the Chicago Symphony Orchestra conducted by Hans Lange. On 17 February 1943 Rachmaninoff played his last recital at the University of Tennessee in Knoxville, Tennessee.

Sergei Rachmaninoff: Symphonic Dances, Op. 45

Rachmaninoff monument in Novgorod, Russia

Rachmaninoff appeared frail, and eyewitnesses feared that he would slip off the pianist’s bench during the performance. Rachmaninoff played some Bach, some Wagner, some Schumann, some Liszt and two of his own etudes tableaux. The program also included, ominously, Chopin’s Piano Sonata No. 2 in B-flat minor, the so-called “Funeral Sonata.” Despite being in obvious pain and visibly exhausted, Rachmaninoff played three encores “closing with one of his greatest hits, the grave, stern Prelude in C-sharp minor.” Critics had often dismissed the prelude “as a shallow and mediocre work,” and the immense popularity made it even harder for Rachmaninoff to reach out with his later works. In terms of his adoring audiences, however, it became a popular hit. Rachmaninoff told a friend that American audience wouldn’t leave the concert hall until he had played it.” And while Rachmaninoff confessed backstage that he was tired of playing it, “it became an effective coda to every single one of his recitals.”

Sergei Rachmaninoff: Prelude in C-sharp minor, Op. 3, No. 2

Rachmaninoff playing a Steinway grand piano, 1936

Rachmaninoff’s cough worsened, as did the pain in his back, and he decided to cancel his three concerts in Texas and travel directly to California. Doctors advised him against the long journey, but Rachmaninoff insisted on his return to Beverly Hills. “That will be my last home on earth,” he said. “There I shall die. I shall gather a little strength, straighten out my fingers, and then play for the last time. After that, let death come…”After an arduous train journey lasting sixty hours, an ambulance took him straight to the hospital, and it became evident that he was suffering from an aggressive form of melanoma. Rachmaninoff was released to his home on 610 Elm Street, and cared for by his wife, his daughter Irina, and the young Feodor Chaliapin Jr. Rachmaninoff apparently said, “They say I am getting better… but I am losing my strength… Don’t the doctors notice this?” Not unexpectedly, in the last week of March 1943 his health rapidly declined.

Sergei Rachmaninoff: Paraphrase of Tchaikovsky’s “Lullaby”

Rachmaninoff was unable to eat as the sight and smell of food became revolting. He also suffered from constant pains in his arms and sides, and he found it difficult to breathe. “I don’t know which way to lie in my bed,” he said. “I think the doctors do not know what is the matter with me. I cannot eat and I am losing my strength.” Rachmaninoff might have guessed the nature of his ailment, but it appears that doctors never fully informed him of his fatal condition. According to his nurse, this was the first time he expressed surrender. “He did not ask to be read to many more, talked less, and often groaned with pain.” On 26 March Rachmaninoff lost consciousness, his body temperature increased and his pulse became irregular. Two days later, on 28 March 1943, Rachmaninoff died four days short of his seventieth birthday. “A message from several Moscow composers with greetings had arrived too late for Rachmaninoff to read it.”

Sergei Rachmaninoff: All Night Vigil, Op. 37, No. 6

Rachmaninoff Statue in Moscow

Rachmaninoff had received last rights on 27 March, and he died a 1:20 a.m. on Sunday, 28 March. A requiem was read over his body at home before it arrived at the Holy Virgin Mary Russian Orthodox Cathedral in the Silver Lake region of Los Angeles. Apparently, Rachmaninoff had been an active member of the parish, and at 8 p.m. a great requiem took place. A second requiem took place on 29 March, and one day later a requiem Mass was held on 30 March. According to newspaper reports, “the small church was filled to capacity with members of the Russian émigré community, Rachmaninoff’s Hollywood friends, and many fellow musicians.” Even the vice-consul of the Soviet Union attended the service. A choir sang his All Night Vigil at his funeral, and his body was placed in a 2,000- pound zinc coffin and held at Rosedale Cemetery until it could be returned to Russian for final burial.

Sergei Rachmaninoff: Prelude in G minor, Op. 23, No. 5

Rachmaninoff indicated in his will that he wished to be buried at Novodevichy Cemetery in Moscow, the resting place of many eminent Russians, including Scriabin, Taneyev, and Chekhov. He had always remembered Chekhov’s remark, “Young man, I see a brilliant future written on your face.” However, his American citizenship and a raging World War II made the transfer of his body impossible. Rachmaninoff had come to the United States as a result of the 1917 Russian Revolution, and according to a biographer, “he lost his native soil, his people, his sounding board. For years his muse was silent, and when he did compose again during the last years of his life, it was only a nostalgic echo of what he had said before.” A scholar writes, “Rachmaninoff’s tragedy was that his Russia was no more, and he could not live without a Russia.” His granddaughter suggested that Rachmaninoff wanted to be buried in Switzerland, but in the event, the burial took place two months after his death in Kensico Cemetery in the town of Valhalla in upstate New York.

Sergei Rachmaninoff: 6 Songs, Op. 8, No. 6 “A Prayer” (Elisabeth Söderström, soprano; Vladimir Ashkenazy, piano)

Grave of Sergei Rachmaninoff

The grave of Rachmaninoff and his wife and daughter are marked with a tall Russian Orthodox cross, “and they are walled on three sides by high hedges.” It appears that many Russian musicians and music lovers are lobbying for the return of Rachmaninoff’s remains to his homeland. Such a possible reburial is in the hands of Rachmaninoff’s grandson and heir, Alexandre Rachmaninoff-Conus, who will have the last word on a possible relocation. Throughout his life, Rachmaninoff pursued three aspects of his musical career with almost equal success. He was a pianist, composer, and conductor, but he admitted “that he found it difficult to concentrate on more than one at any given time.” He composed little during the later stages of his life, “his reputation as a composer perhaps falling victim to his success as a pianist.” Rachmaninoff’s pianism was described with great gusty. A critic writes, “The direct expression of a work, the extraordinary precision and exactitude of his playing, and even the strict economy of movement of arm and hands which M. Rachmaninoff exercises, all contributed to the impression of completeness of performance…” Contrary to the warmth and generosity of his personality he revealed in the company of his family and close friends, his concert manner was austere. Surely one of the greatest pianists of the 20th century, Rachmaninoff’s playing was marked by a formidable piano technique, “and by a rhythmic drive, refined legato and the ability to completely clarify complex textures.”

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter

Sergei Rachmaninoff: Piano Concerto No. 3 in D minor, Op. 30

Seventy is too early an age to die for an artist of such genius, especially considering the undiminished quality of his last works. He has enriched the lives of many people.

Yes in a world of turmoil (his music has the struggle with this too), he has shown us the heavenly realm can be experienced here and his calming, soulful, loving work gives us a glimpse at eternity (a peek behind the door so to speak). I wish to take a trip to see New England soon, and plan paying visit to his grave for his inspiration and thank him the music.

Rachmaninoff’s compositions will be played by a wonderful pianist, Susan, at the Oak Ridge High School Performance Threater on Feb. 15, 2025 @ 7:00PM along with the fabulous Oak Ridge Symphony Orchestra.