“The Garden of Love” by Rubens

One of the cleverest of the polyphonic tricks was by an otherwise anonymous composer, who took as his subject the English architect with a name that was so ripe for ribaldry: Inigo Jones. When his first name was reduced to its syllables: In – I – Go Jones, the proper name is made into a verb and much fun ensues.

Anonymous: Inigo Jones

A contemporary of this anonymous, the composer and organist John Isham, describes “Celia Learning on the Spinnet”, where her tutor shows her how to place her hands.

Isham: Celia Learning on the Spinnet

It is the composer Henry Purcell, who we remember more for being organist at Westminster Abbey and of the Chapel Royal and one of the founders of English opera, than as composer of dirty songs, who really took this genre further. He had occasion to write a bit on the sexy side and used it for commentary on society. As Sir Walter (presumably Raleigh) dallies, we hear his lover get complete caught up in the moment:

Purcell: Sir Walter enjoying his damsel, Z. 273

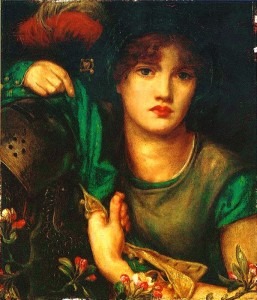

“My Lady Greensleeves” by Dante Gabriel Rossetti

Purcell: The Mock Marriage, Z. 605: Man is for the woman made

One of the most famous of the English Renaissance songs, and one that is probably still familiar to most people today is “Greensleeves.” That opening line “Alas, my love you do me wrong…. “ is taken as so high-brow and refined in its gentle protest as being cast off. But, what do the “greensleeves” really refer to? It is a typical Elizabethan reference to those troublesome green stains one got on one’s clothing after a tumble in the green green grass.

Anonymous: Greensleeves (The King’s Singers)

This is made most clear in Morley’s spritely “Now is the Merry Month of Maying” and that reference to “each with his bonny lass, upon the greeny grass.”

Morley: Now is the Month of Maying (Cambridge Singers; John Rutter, cond.)

Another pastoral madrigal follows the shepherdess Fair Phyllis. She was missing and her lover Amyntas went to find her, searching “up and down,” but in a way that makes you wonder what exactly was going in those directions. It all decorously with kisses, but that middle section makes you wonder!

Farmer: Fair Phyllis (Oxford Camerata; Jeremy Summerly, cond.)

Hello, I am singing “of all the birds that I do know” with a group of people. It seems to me to have so many sex innuendoes. Do you know if and where I can get information about this song? I would be most grateful.

Reply from Maureen:

Well, it’s all there in your imagination!

By putting the bird in the place of his lover, he’s able to talk about things in a coded manner – he can describe her rising, her going to bed, and what she will do at his command “With lips with teeth, with tongue and all. / She chants, she chirps, she makes such cheer…”, the cheer being felt from the poet’s side.

The strange thing, of course, is that ‘she’ is named ‘Philip’(and not Philippa), but that may have more to do with the fact that “Philippa my sparrow” is very difficult to say/sing:)