During a 1928 lecture for choral conductors in Berlin, Paul Hindemith addressed the widening gap between contemporary composers — and here he particularly emphasized Arnold Schoenberg — and the general musical public. “The tenuous connection in music today between producers and consumers is to be regretted. The composer today should write only if he knows for what purpose he is writing. The days of composing for the sake of composing are perhaps gone forever. On the other hand, the demand for music is so great that it is urgently necessary for composers and users to come to an understanding of each other.” Hindemith’s engagement with the musical “Jugendbewegung” (Youth Movement) — at that time void of the political overtones it would subsequently acquire — resulted in specific compositions for use (Gebrauch), including the short children’s opera Wir bauen eine Stadt.

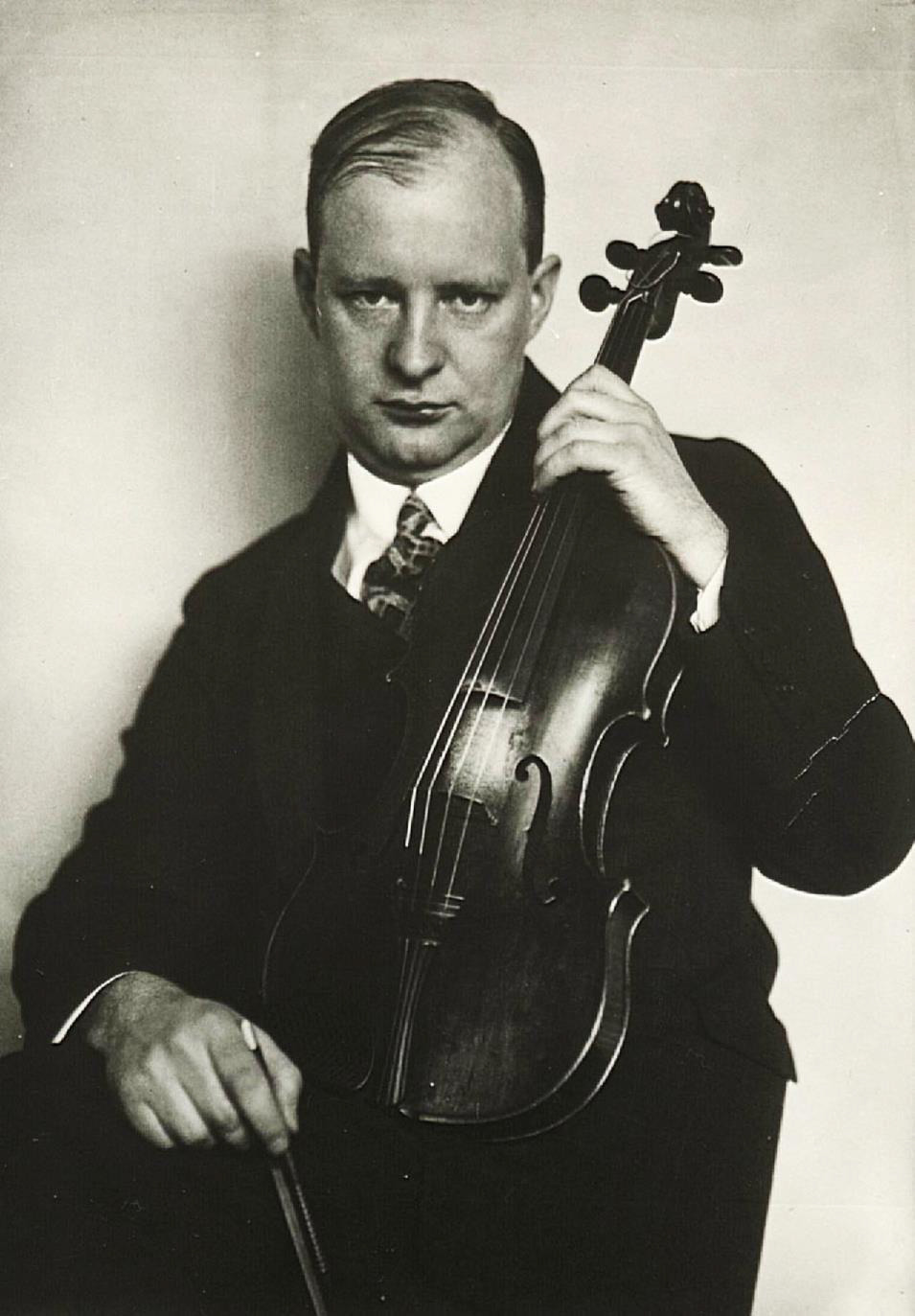

Paul Hindemith (1895 -1963)

Paul Hindemith: Wir bauen eine Stadt (Leipzig Radio Children’s Choir; Studio ensemble; Hans Sandig, cond.)

Containing a diversity of genres, including speaking and acting roles and even audience participation, Hindemith’s “Gebrauchsmusik” marked the beginning of a compositional aesthetic the composer would maintain for the rest of his life. In 1952, Hindemith famously wrote, “It is not impossible that out of a tremendous movement of amateur community music a peace movement could spread over the world? People who make music together cannot be enemies, at least no while the music lasts.” The emphasis on the useful and practical, rather than music being a vehicle for self-expression also brought with it a change of musical language. Contrary to his densely contrapuntal neo-classical style, the emphasis now shifted towards the lyrical, with melody and accompaniment seemingly derived from vocal music.

Paul Hindemith: Concert Music for Viola and Large Chamber Orchestra, Op. 48 (Raphael Hillyer, viola; Louisville Orchestra; Jorge Mester, cond.)

Franz Magnus Böhme

The primary aim of the musical “Jugendbewegung” was the promotion of national folk music and German Renaissance popular song. For Hindemith, the discovery of these new repertories “was the nourishing foundations of much of my music.” Hindemith principally relied on the Altdeutsches Liederbuch (Old German Songbook) published by Franz Magnus Böhme in 1877. On 800 pages, Böhme published roughly 660 sacred and secular folk songs and chorales, all originating between the 12th and 17 century. With some frequency, these sources became part of Hindemith’s music language, either quoted directly or imitating its folk-like characteristics. It is hardly surprising that they numerously appear in the dramatic allegory Mathis der Mahler, based on the German painter Matthias Grünewald.

Paul Hindemith: Mathis der Maler – Tableau I Scene 2: Es wollt ein Maidlein… (Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau, baritone; Urszula Koszut, soprano; Bavarian Radio Symphony Orchestra; Rafael Kubelik, cond.)

Hindemith’s folk-music research for Mathis also provided the foundation for a concerto for viola and small orchestra entitled Der Schwanendreher (The Swan turner). This somewhat curious title does not refer to a cook’s assistant who turns the spit upon which a swan is roasted — as is frequently claimed — but as Hindemith explains in his preface, “to a wondering medieval minstrel, or organ grinder, who plays a the hurdy-gurdy which has a handle in the shape of a swan’s neck.” So turning the Swan, in the context of this concerto, means to make music. The title of the work shares its name with the German folksong that prefaces the third movement, “Seid ihr nicht der Schwanendreher” (Aren’t you the swan turner). The opening movements are based on medieval German folk songs as well, the first appropriating “Zwischen Berg und tiefem Tal’ (Between mountain and deep valley). The second movement quotes two folksongs, “Nun laube, Lindlein laube,” (Grow leaves, little linden tree, grow leaves), and “Der Gutzgauch auf dem Zaune sass” (The Cuckoo sat on the fence).

Paul Hindemith: Der Schwanendreher (Geraldine Walther, viola; San Francisco Symphony Orchestra; Herbert Blomstedt, cond.)

In Der Schwanendreher Hindemith draws exclusively upon Böhme’s publication, and his third organ sonata of 1940 makes references to folk songs even in the title. Whether Hindemith employs folk tunes “in a specific dramatic context, as thematic material for instrumental pieces, or humorously (never ironically in Mahler’s manner), they run through his life’s work in accordance with his maxim that only that which is rooted in tradition has claimed to permanence.” Upon Hindemith’s death, Oskar Kokoschka wrote a letter to Gertrud Hindemith, “It is with truly profound sadness that I have heard on the radio about the great loss that you, Madame, and the world spiritual community are suffering. I am all the more sorry at a time that seems so decidedly in favour of dispensing with artistic achievement as the present time, that an artist who still has so much to say leaves us prematurely.” Yet Hindemith was not universally acclaimed, as Theodor Adorno called his music “symptomatic of a false social consciousness,” and condemned it as “being not truly useful at all.” Hindemith’s final compositions, in turn, represent his embittered rejection of modernity as a tainted ideal. Paul Hindemith was one of the most prolific composers of the 20th century — he composed nearly 300 major works — but his music has found less public acceptance than those of his contemporaries Stravinsky, Bartok, and Schoenberg. He was uncompromising and highly critical of Schoenberg as a teacher, theorist and composer and thereby initiated the ongoing discussion of the role of music and the artist in contemporary society. It is hardly surprising therefore that everybody was gunning for the messenger!

For more of the best in classical music, sign up for our E-Newsletter