George Frideric Handel (1685-1759) was one of the all-time great composers. Restless and resourceful, Handel was a workaholic musician of great charisma with a genius for invention. For most of his life—at least during his time in London—Handel operated as an independent contractor. No longer on the royal payroll, he became the first musician-entrepreneur who was not afraid to take financial risks. He carefully builds a network of friends and wealthy benefactors, among them the 3rd Earl of Burlington and the 4th Earl of Cork, both young and incredibly wealthy members of an Anglo-Irish aristocratic family.

Handel’s memorial at Westminster

The Duke of Chandos became one of his most important patrons, and highly significantly, he was the main subscriber to Handel’s new opera company, the “Royal Academy of Music.” Initially, Handel worked as a salaried director of the opera company, but when the original financial backers lost all their money in the South Sea bubble, Handel was ordered to take over the reins. The story goes that the Bank of England kept a window open late at night for Handel to deposit his evening takings. In the event, he took £21,000 to the bank and turned it into £2 million in today’s money. Now that’s what I call a financial success story.

George Frideric Handel: Chandos Anthem 6A (Academy of St. Martin in the Fields Orchestra; David Willcocks, cond.; King’s College Choir, Cambridge; April Cantelo, soprano; Ian Partridge, tenor)

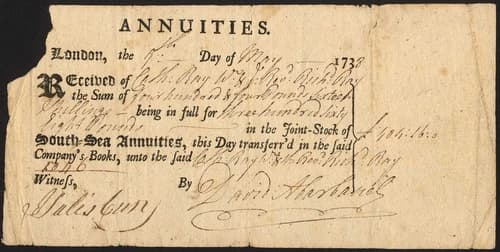

South Sea Company Annuities

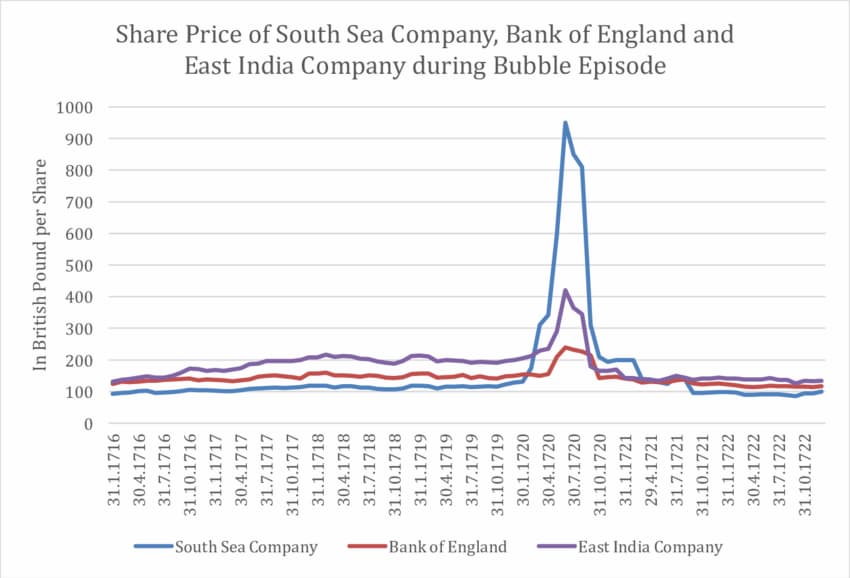

We know a good deal about Handel’s approach to finances as the Bank of England kept detailed records of his investment transactions. Like a good many investors, Handel initially made a highly risky foray into the stock market by buying individual shares in the notorious South Sea Company. That company was founded in 1711 and promised a monopoly on trade with Spanish South American colonies by the British in exchange for taking over the national debt raised by the War of Spanish Succession. Handel apparently bought South Sea stock around 1715 and sold them between 1717 and 1719, just one year before the share price suffered its spectacular collapse. Handel was lucky and probably made some profit, but he had made the classic mistake of buying individual shares during a time of innovation and speculation in “an immature and relatively unregulated market.” Sir Isaac Newton was not so lucky. He was still invested in shares when the South Sea Company went bust and only sold his holdings when the share price had collapsed well below his buying price. Reportedly, he lost roughly £3 million in today’s money, but he nevertheless took a philosophical view. “I can calculate the movement of the stars,” he said, “but not the madness of men.”

George Frideric Handel: Giulio Cesare in Egitto, HWV 17 “Act III” (Susan Gritton, soprano; Ann Murray, mezzo-soprano; Patricia Bardon, mezzo-soprano; Katarina Karnéus, mezzo-soprano; Christopher Robson, counter-tenor; Axel Köhler, counter-tenor; Marcello Lippi, baritone; Jan Zinkler, baritone; Bavarian State Orchestra; Ivor Bolton, cond.)

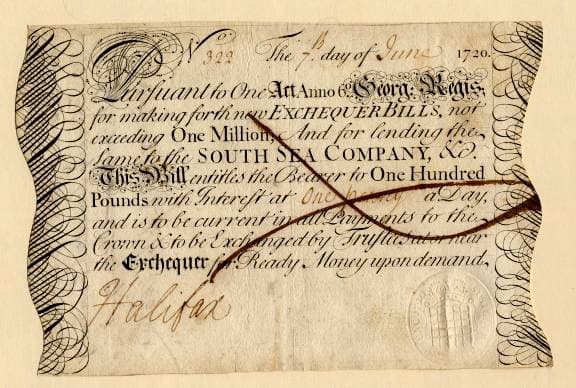

South Sea Company bubble note signed by the Earl of Halifax

Handel had a lucky escape, and he knew it. His South Sea Company adventure would turn out to be the first and only time he owned shares. From then on, he decided to get involved in safer assets that paid a steady income. The collapse of the South Sea Company led to a public outcry and the government was urged into compensating the huge number of failed investors. As such, they converted half of the South Sea shares into bonds guaranteeing a fixed annual income for investors. The conversion took place in June 1723, and these government bonds paid 5 percent annual interest. And as you might have guessed already, Handel got involved and purchased roughly £150 worth of bonds, valued today at around £21,000. And additional cash was flowing in freely as well. When he premiered his oratorio Athalia in Oxford in 1733, 3,700 people attended one of its earliest performances. By the time the oratorio had completed its first run, Handel had pocketed roughly £400,000 in today’s value.

George Frideric Handel: Athalia, HWV 52 (Emma Kirkby, soprano; Joan Sutherland, soprano; Anthony Rolfe-Johnson, tenor; James Bowman, counter-tenor; David Thomas, bass; Aled Jones, vocals; Oxford New College Choir; Academy of Ancient Music; Christopher Hogwood, cond.)

Share price of South Sea Company Bank of England and East India Company, 1716-1722

For more than a decade Handel traded in and out of South Sea Annuities, seemingly making little profit. Frequently he would sell all his bonds, presumably to stage one of his operas, and subsequently reinvest the theatre profits. Buying and selling of shares and bonds was rather cumbersome in Handel’s days, as the composer was required to visit the Bank of England in person if he wished to make a trade. Hardly surprising that Handel was frequently seen traveling from his home in Mayfair to the Bank of England. Preoccupied with his musical endeavors, Handel took a break from the market for about 10 years. However, he re-entered the market in 1743 by investing £1,500 in South Sea Annuities. By the time of his death in 1759, his portfolio had grown substantially. Although he had switched to a 3 percent consolidated government bond, his yearly investment would have been roughly £71,000 in today’s money. And by the time of his death, his holding was worth about £2 million in today’s money. I would call that a proper reason to celebrate.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter

George Frideric Handel: Music for the Royal Fireworks, HWV 351 (Academy of St. Martin in the Fields Orchestra; Neville Marriner, cond.)

Such interesting reading to know what these Composers were like

This is fascinating. I did not know this aspect of Handel’s life. Mozart might have done very well in England – Fate prevented him from establishing himself there.