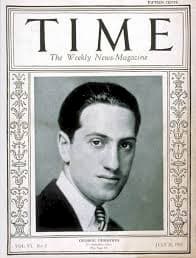

George Gershwin, 1934

It has been said that the total royalties George Gershwin accrued from performances of “Summertime” from his opera Porgy and Bess are equivalent to the Argentine national debt. Whether there is any truth to that anecdote or not, Gershwin was filthy rich, and he wasn’t shy apprising people of that fact. When Gershwin met Stravinsky and asked to take lessons, he was supposedly asked how much money he made. When Gershwin named an astronomical sum, Stravinsky told him “Then I should take lessons with you.” Stravinsky insisted later that this exchange never took place and that he had heard the money story from Ravel. Today we know that it was Gershwin himself who floated that story. Regardless, how did Gershwin rise from a school dropout and song plugger—basically a salesman and staff pianist who promoted a Tin Pan Alley music-publishing firm—to become the biggest cheese on the block? The short answer is that he brought the economic experience of popular music to the concert hall.

Gershwin, 1934

Gershwin was raised in the world of Tin Pan Alley and Broadway, where success was defined by the for-profit strategies of hit songs. Ambitious in his artistic dreams and in his quest for financial reward, Gershwin set out to bring the “hit song” into the concert hall. It has been suggested, “Gershwin’s strategies for wealth, fame, and artistic achievement were all part of the same ambition to write great music that would reach large audiences. Musical excellence was a market opportunity; melody propelled by original, sophisticated music would triumph as art and as product.” So he set out to write great music as he was convinced that great music would sell. Scholars have used An American in Paris as a case in point. This orchestral tone poem was not commissioned, and Gershwin received no fee for composing it. When the work premiered in December 1928, it quickly established Gershwin’s reputation and he “leveraged this success not only for subsequent concert performances, but also for a series of radio, recording, publishing, and stage projects that within one year reached large audiences and returned significant financial rewards.”

George Gershwin: An American in Paris (Pittsburgh Symphony Orchestra; André Previn, cond.)

Gershwin on Time Magazine cover, 1925

In 1918, Gershwin signed a contract with Thomas B. Harms Music Publishing Company, a firm that would combine with the English firm of Chappell, Inc. to publish over 90 percent of all Broadway songs. This contract granted the publisher exclusive and comprehensive ownership of Gershwin’s music, and of any collaborating lyricist. The composer was at liberty to compose for any Broadway production company as long as the music would be published exclusively by Harms. In exchange, Harms promised to publish any and all the works created by the composer. Gershwin also received an initial royalty of three cents per copy for each piece of sheet music sold, and he was given a weekly salary of 35 dollars. His first hit “Swanee,” with lyrics by Irving Caesar, propelled to stardom by the blackface performer Al Jolson, sold more than 2 million recordings and 1 million copies of sheet music. Gershwin claimed to have written that song in “about an hour,” on a bus ride. From then on, there was no looking back and Gershwin churned out hits with incredible speed, sometimes up to 6 songs a day. It even got bad enough that he had to publish his music under pseudonyms such as Fred Murhta and Burt Wyn, so people didn’t get tired of seeing the name Gershwin on the cover of every score.

George and Ira Gershwin

To put things into perspective, during the 13 years of almost exclusive collaboration between George and his brother Ira, they produced nearly 1000 songs, a dozen shows and four films. However, sheer mass of production was not exclusively responsible for Gershwin’s financial success. He was, above all, always at the forefront of music technology. While his first music was sold in the form of sheet music, piano rolls and records, by the time he achieved national attention public broadcast radio was the new revolution. And Gershwin caught onto this latest development immediately as it collapsed the space between the creation of his music and its popular reception. He earned money from publications and performances, but also from recordings, broadcast right, and licensing. And it was this financial independence that gave him the freedom to compose his larger works. Gershwin tragically died at age 38 without making a will, and his estate passed to his mother. The Gershwin estate continues to collect song royalties as a recent copyright amendment decreed that works written jointly would not become public domain until 70 years after the death of the last surviving co-author. Ira Gershwin outlived his brother by nearly half a century, which means that the Gershwin estate will collect song royalties until 2053.

Gershwin was a genius!

I meet a senior older woman several years back in Atlanta about 1995 and she told me her last name was Gershwin and that she had been the wife of a musician. she said she graduated from Columbia University and helped develop a filing system called duewe decimal and moved to California where she worked in state government for many years filing state code records. she had olive complexion and appeared to be Hawaiian or Asian. I was wondering could she have been telling the truth. in 2004 I went into a music instrument store in Decatur ga. that dated back to 1890. it was owned by the same family all those years. I was buying my son a violin at the time he was 14 years old. one of the salespeople mentioned the name Gershwin about being a composer which I know nothing about. and further said that they had met a Gershwin family member in their store. I was just curious about my encounter.

Next week will be 125th anniversary.of George Gershwin birbirth! Mazeltov!