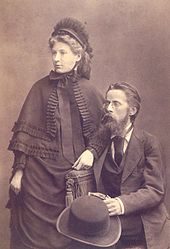

Elisabeth von Herzogenberg

Johannes Brahms: Rhapsody in B minor, Op. 79 No. 1

Johannes Brahms

Johannes Brahms: Rhapsody in G minor, Op. 79 No. 2

Elisabeth was normally full of praise for most of his work, “your music forms an integral part of our lives,” she writes, “like the air and light and warmth.” However, she was not uncritical and expressed her reservations in a manner that did not cause offence. “I have an unfortunate love of truth,” she wrote, and when Brahms sent her a number of songs and choral pieces, she responded as follows. “I would not dare to say a word about what fills me with enthusiasm in these sets, if I were to remain silent about what fails to move me.” Brahms, at any rate, held her in high esteems and wrote, “you should know and believe that you are among the few persons whom one holds so dear that one cannot tell them so.” Apparently, Brahms had Elisabeth’s photograph on his writing desk. One day, according to his housekeeper, Brahms had “given Elisabeth the empty frame and suggested that she put her own husband’s portrait in it.” Minor misunderstandings aside, there have never been any serious tensions between them.

Elisabeth was normally full of praise for most of his work, “your music forms an integral part of our lives,” she writes, “like the air and light and warmth.” However, she was not uncritical and expressed her reservations in a manner that did not cause offence. “I have an unfortunate love of truth,” she wrote, and when Brahms sent her a number of songs and choral pieces, she responded as follows. “I would not dare to say a word about what fills me with enthusiasm in these sets, if I were to remain silent about what fails to move me.” Brahms, at any rate, held her in high esteems and wrote, “you should know and believe that you are among the few persons whom one holds so dear that one cannot tell them so.” Apparently, Brahms had Elisabeth’s photograph on his writing desk. One day, according to his housekeeper, Brahms had “given Elisabeth the empty frame and suggested that she put her own husband’s portrait in it.” Minor misunderstandings aside, there have never been any serious tensions between them. When Elisabeth died on 7 January 1892 from heart disease, Brahms was devastated. He had come to rely on her musical judgment and criticism, and confided in her husband. “It is vain to attempt any expression of the feelings that absorb me so completely. You know how unutterably I myself suffer from the loss of your beloved wife, and can gauge accordingly my emotions in thinking of you, who were associated with her by the closest possible human ties. I preserve in them [Elisabeth’s letters] above all one of the most precious memories of my life, and furthermore a rich treasure of feelings and wit, which, of course belongs to me alone.” In 1880, Brahms had dedicated his Rhapsodies Op. 79 to Elisabeth, and after her death he arranged for the publication of her eight pieces for piano.

Elisabeth von Herzogenberg: Eight Klavierstücke, “Andante”

Isn’t so that Brahms dedicated his first sonata for violin and piano in G-major to Elizabeth?