For lots of reasons, being married to a composer can be difficult.

However, sometimes composers get lucky and find perfectly suited spouses who support them, encourage them, and even inspire their work.

In the second part of this two-part series, we’re looking at what made ten of the happiest marriages in classical music so successful. We’ve counted down from number ten to number six in Part I, and will pick the countdown up again at number five.

5. Edward Elgar and Caroline Alice Roberts

Edward and Alice Elgar, circa 1891 © Wikipedia

Alice Roberts was born in 1848 in India to a prominent British family. She was an intelligent child, and made an extensive study of music and languages (including English, she spoke five). She was also a talented writer, publishing a two-volume novel called Marchcroft Manor in 1882.

In the autumn of 1886, when she was thirty-eight years old, she decided to take accompaniment lessons from a local piano teacher. Those lessons would change forever, because the teacher was thirty-year-old Edward Elgar.

Student and teacher fell in love and got engaged, setting a wedding date for the spring of 1889. Her family was appalled. Elgar had three strikes against him: he was poorer, younger, and Catholic.

But Alice and Edward didn’t care what others thought. As a wedding present, she gave him poetry that she’d written, while he gave her a sweet piece for violin and piano called Salut d’Amour, which ended up becoming one of his most famous pieces.

Edward Elgar: Salut d’Amour

They had one child together, Irene, in 1890.

Although Elgar struggled with money in the early part of their marriage, Alice remained a steadfast support and cheerleader. She helped out by taking care of things like networking, promotion, and administrative issues so that Edward could focus on composition. In the process, she gave up some of her own creative endeavours. She once wrote in her diary, “The care of a genius is enough of a life work for any woman.”

Even though she had less and less time to write poetry, Elgar was inspired by what his wife did write. He wrote seventeen songs that employed her poetry and dedicated the first of his Enigma Variations to her.

It must have been incredibly satisfying when Elgar was knighted in 1904, and she became Lady Elgar.

In 1920, Alice began showing signs of illness. She was eventually diagnosed with lung cancer and died in April 1920.

Edward survived for fourteen more years, dying in 1934. The pace of his creative output slowed dramatically after her death. Read more about Edward Elgar and Caroline Alice Roberts.

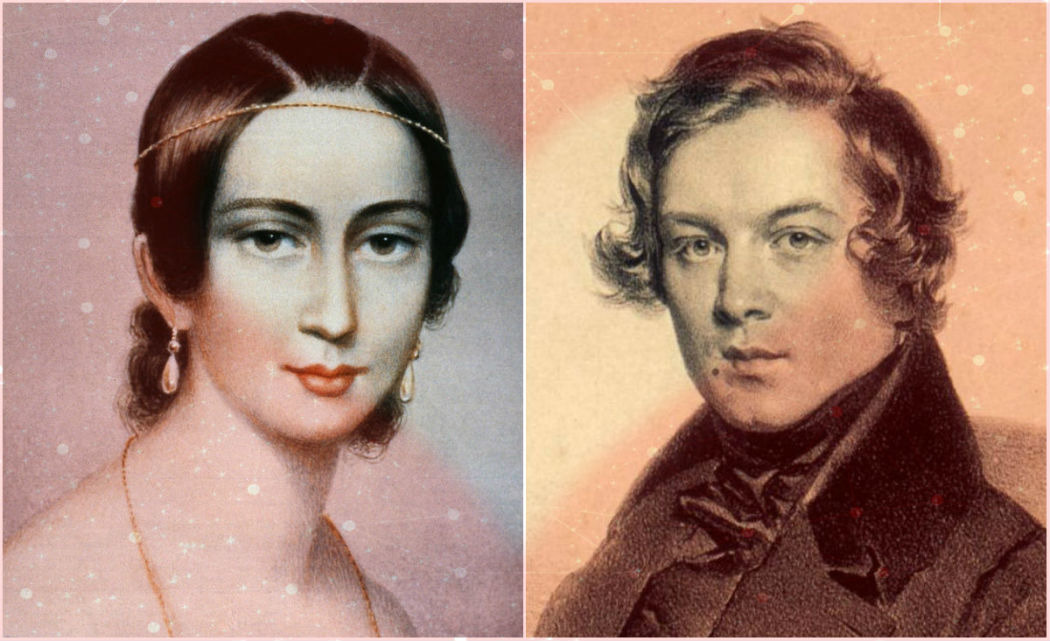

4. Robert Schumann and Clara Wieck

Robert and Clara Schumann © wrti.org

In 1828, nine-year-old piano prodigy Clara Wieck performed at a Leipzig house concert. While there, she was introduced to an eighteen-year-old musician named Robert Schumann, who was so astonished by her abilities that he decided he wanted to study under Clara’s teacher, who also happened to be her father. He rented a room in the Wieck household while taking lessons and became a family friend.

During Clara’s teens, the two collaborated on various musical projects. When she was eighteen, Robert proposed. Her father was horrified at the idea of their marrying and refused to grant permission, so – in a daring move – Clara and Robert decided to go to court and sue him.

Much drama ensued over the following years, but in the end, the court granted them permission. They married on 12 September 1840, one day before her twenty-first birthday.

Encountering Robert & Clara Schumann (Documentary)

Robert’s wedding gift to Clara was a joint marriage diary. They kept it for four years, giving priceless insight into their relationship, their love of music, and their dual careers.

That said, not everything was rosy between the two. They had arguments about Clara’s desire to go on tours, and Robert frequently infantilised his younger wife. Both struggled with their mental health, but especially Robert, who began acting more and more erratically.

In February 1854, Robert attempted suicide by jumping into the Rhine River. He was saved, but it was clear that drastic measures needed to be taken to keep him alive, and he agreed to relocate to an asylum. Tragically, he would die there two years later, and Clara would only see him once more, a few days before his death. However, even in his weakened and delirious state, Robert recognised her.

She never fully recovered from his death, although she would have an intense lifelong friendship with her beloved colleague Johannes Brahms.

3. Benjamin Britten and Peter Pears

Benjamin Britten and Peter Pears at the Old Mill, Snape, in 1943 © Britten-Pears Foundation

Composer Benjamin Britten and tenor Peter Pears were never able to marry, but their lifelong partnership was sturdier than most legally sanctioned marriages, and it richly deserves a place on this list.

The two men first spent time together in 1937, when they helped to clean out the house of a friend who had passed away suddenly in a plane crash.

Britten was immediately inspired by Pears, writing his first work for him within weeks of their meeting. He began taking on the role of Pears’s accompanist.

For a while, the two were just close friends. However, in the spring of 1939, they traveled to America to give a recital tour together, and they became lovers on the trip. Their lives would remain entwined until Britten died in 1976 in Pears’s arms.

Britten and Pears: ‘A Life of the Two of Us’

Peter Pears was the muse for many of Britten’s most famous works, including the opera Peter Grimes, The Rape of Lucretia, and the War Requiem.

The two men also worked together to mount the prestigious Aldeburgh Festival in Suffolk, England, a festival that continues as a testament of their love to this day.

Their surviving letters give a window into their love: “My darling heart – I do love you so terribly… you are the greatest artist that ever was,” the usually reserved Britten once wrote to Pears.

2. Olivier Messiaen and Claire Delbos

Claire Delbos and Olivier Messiaen © Wikipedia

Claire Delbos was born in Paris in 1906. She was a musical child and studied violin and composition at the Paris Conservatoire.

While there, she met a fellow student two years her junior named Olivier Messiaen. They became friends and began performing recitals together. Eventually, they fell in love, and they married in the summer of 1932.

Messiaen’s wedding gift was his “Thème et variations” for violin and piano, which they premiered together in concert in 1932. Claire reciprocated with music composed for her husband.

Olivier Messiaen: Theme and Variations

This creative dialogue continued throughout their marriage. Messiaen even wrote a song cycle about the joys of marriage called Poemes pour Mi (Mi being his nickname for his wife).

The two were deeply in love. That love never wavered, even in the face of the trauma of multiple miscarriages. Finally, in 1937, after years of struggle, Claire gave birth to a healthy baby boy named Pascal. It was an overwhelming moment.

The two were parted in 1940 when Messiaen was drafted into the French army to fight the Nazis. He was eventually captured and sent to a prisoner-of-war camp. While there, he wrote arguably his most famous piece, Quartet for the End of Time. It’s tempting to read his longing for the love of his wife into the work.

Their two-year separation was deeply painful for both of them. To make circumstances more tragic, as soon as the war ended in 1945, it became clear that Claire was becoming oddly forgetful.

In 1949, it was determined that she needed to have a hysterectomy. Disaster struck on the operating table. She reacted badly to the anaesthetic and emerged from the surgery with debilitating mental issues. Her condition became severe enough that Claire needed to move full-time into a nursing home.

She ended her life blind and unable to recognise people, including her adoring husband. She died in 1959.

After her death, a devastated Messiaen broke down in front of his recital partner and former student Yvonne Loriod: “Something horrible has happened. Claire died on Wednesday, I just got back from the funeral… Don’t leave me, you’re young and alive.”

Yvonne didn’t leave, and in 1961, she became Messiaen’s second wife.

Losing a beloved spouse in such a painful way shattered Messiaen, and after her death, he was rarely able to speak about her except to call her a saint. Even today, there are many things we don’t know about her, despite Messiaen’s importance to twentieth-century music and Claire’s importance to his music. Read more about Messiaen’s love story.

1. Richard Strauss and Pauline de Ahna

Richard Strauss and Pauline de Ahna © Time Life Pictures/Mansell/Getty Images

Pauline de Ahna was born in 1863 in Ingolstadt. She was extremely musical and studied at the Munich Musikschule, the school where Richard Strauss’s famous horn-playing father was a professor.

In 1887, she met Richard for the first time when he took a job conducting for the Bavarian State Opera, and began taking voice lessons from him.

When Pauline made her professional debut in 1890, playing Pamina in The Magic Flute in Weimar, it was Richard Strauss who was on the podium. She also worked with him in performances of Wagner and Humperdinck, and even originated the role of Freihild in Strauss’s first opera Guntram.

While rehearsing for Guntram, Pauline had made an impression by throwing the piano score at Richard in front of the orchestra and then storming offstage. He followed her, and the orchestra waited with suspense for his return. When he finally came back, he was asked how he was going to deal with her. “I’m going to marry her,” he said simply.

They were married a few months later in September 1894.

The couple had one child together, Franz, in 1897. After his birth, Pauline retired from performing in operas, although she did still appear in recitals.

But her voice lived on in Strauss’s works; his female roles contain some of the most glorious music of the twentieth century.

Richard Strauss: Symphonia Domestica

He also wasn’t shy about letting everyone know how passionately in love they were. In 1903’s Symphonia domestica (“Domestic Symphony”), a 45-minute tone poem, the work’s program follows the day of a couple at home with a baby. In the middle of the work, there is a very erotic interlude, during which the wife’s melody appears over the husband’s, giving us a very clear (maybe too clear) view into the Strauss marriage.

They stayed in love for the rest of their lives. When she was eighty, Pauline proclaimed to a friend, “I would still scratch the eyes out of any hussy who was after my Richard.”

Richard Strauss died in September 1949, and Pauline in May 1950. It was the end of arguably the happiest marriage in classical music history. Read more about Richard Strauss and Pauline de Ahna’s love story.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up for our E-Newsletter