If a concerto for two soloists is called a double concerto, then it follows that a concerto for three soloists is called a triple concerto. When I started researching for this blog I discovered something interesting about the triple concerto. A good many pieces labeled “concerto grosso,” which feature a small group of soloists that share musical material with a full orchestra can actually be called triple concertos. Such formations were rather popular throughout the Baroque period, and we will listen to some great examples.

A triple concerto performance

We then find the occasional triple concerto during the classical and early Romantic periods, but then it completely disappears. It might well be connected with the rapid rise of the traveling virtuoso, who was unwilling to share the limelight with two others. I can’t see Paganini or Liszt, or hundreds of other would-be egomaniacs, freely giving up stage exposure. As is true in some other contexts as well, it seems that three was considered a crowd. There simply aren’t any Liszt, Rachmaninoff, Schumann, Saint-Saëns, Brahms, or Prokofiev triple concertos around. However, composers in the 20th and 21st centuries, inspired by neoclassical considerations and smaller ensemble groupings, returned to that particular genre. And I was truly surprised at the sheer number of contemporary triple concertos. Enough talking, let’s get started with possibly the most famous triple concerto, the one composed by Ludwig van Beethoven in 1804.

Ludwig van Beethoven: Triple Concerto for violin, cello and piano in C Major, Op. 56

Archduke Rudolph

The Beethoven “Triple” is unique, even for Beethoven. He probably would not have attempted the composition were it not for the intended piano soloist, the sixteen-year-old Archduke Rudolf. The Archduke was his student, and it was difficult to say no to royalty, even for Beethoven. Audiences and critics didn’t like the work, but Beethoven somehow had to accommodate three soloists with different technical proficiencies. So he came up with a stylistic and formal hybrid that works on multiple levels. It is a solo concerto in which the soloists change from passage to passage, but it is also a trio, “in which three musicians perform chamber music on stage.” And then it is also a trio with orchestra, with the trio performing together with a full orchestra. As a musicologist wrote, “the problems are vexing: balancing the three distinctly different timbres of the solo instrument with the orchestral body; allotting the themes equitably to each soloist and the orchestra; creating materials terse enough that they do not become unmanageable, yet flexible enough to do duty for all involved.” It seems that Beethoven was particularly worried that the cello could get lost in that sonic jungle, so he puts the instrument in its top register and has it introducing most of the thematic material. As far as we know, the work was performed only once during Beethoven’s lifetime. While we are talking about designer triple concertos, let’s not forget about Mozart’s Concerto for 3 pianos.

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart: Concerto for 3 pianos, K. 242 “Lodron”

Mozart in 1777

Thanks to an inscription on a special presentation copy, we know exactly why Mozart composed his Concerto for Three Pianos and Orchestra, K. 242. The inscription reads for “Her Excellency, Her Ladyship, the Countess Maria Antonia Lodron and her daughters, their Ladyships the Countesses Aloysia and Giuseppa, 1776.” It was a difficult task for Mozart, as the Countess Lodron was the sister of Archbishop Colloredo, and the wife of Count Arco, with whom Mozart had seriously stormy relationships. Colloredo had little respect or admiration for the young Mozart. In fact, he strongly objected to his habit of disappearing for months at a time on the various European tours arranged by his father. And we know that Count Arco terminated Mozart’s employment in Salzburg in May 1781 by unceremoniously delivering a swift kick to the composer’s backside. The Lodron daughters took lessons with Leopold Mozart and later with Mozart’s sister Nannerl, and the different keyboard proficiency of mother and daughters is clearly reflected in Mozart’s keyboard writing. Two of the solo parts present moderate difficulties, while the younger daughter’s piano part remains comparatively simple. And I suppose that was the real challenge for Mozart in having to write a brilliant concerto that was not too difficult. Musically speaking, Mozart could easily solve any and all problems, and he liked the result so much that he quickly created a version for two pianos as well.

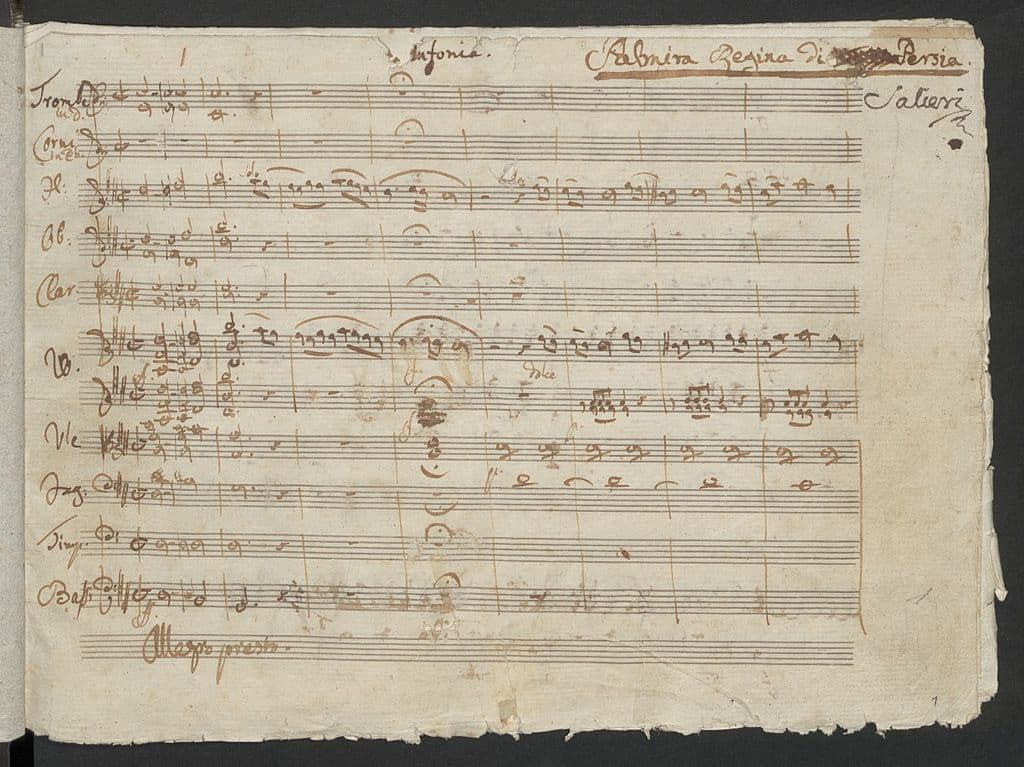

Antonio Salieri: Concerto for Oboe, Violin, and Cello in D Major

Antonio Salieri: Concerto for Oboe, Violin, and Cello in D Major

With Mozart leading the way, Antonio Salieri can’t be far behind. He was only twenty-four when the Emperor appointed him royal court composer in Vienna, and he later became the Imperial Royal Kapellmeister in 1788. Salieri was a prolific composer, who wrote forty-three operas, works he presented in many respected European locations. In the famous movie Amadeus, Salieri is called “the patron saint of mediocrities,” but that seems rather harsh. A scholar writes, “His opera is thrillingly melodic, impeccably crafted, and undeniably innovative.” His triple concerto for oboe, violin, and cello in D Major clearly bears witness to his gift for opera. A commentator writes, “Of course, dialogue is a central feature of the concerto form per se; but the way Salieri has the solo instruments speak to one another betrays the hand of the practiced opera composer. On the one hand, there is a lively exchange of ideas between the three soloists, and on the other, dialogue of equal interest takes place between the solo group and the accompanying orchestra.” In a way, the musical substance is exclusively derived from melodic inspirations, and not from any kind of formal development.

Antonio Salieri: Concerto for Oboe, Violin and Cello in D Major (Lajos Lencsés, oboe; Béla Bánfalvi, violin; Károly Botvay, cello; Budapest Strings)

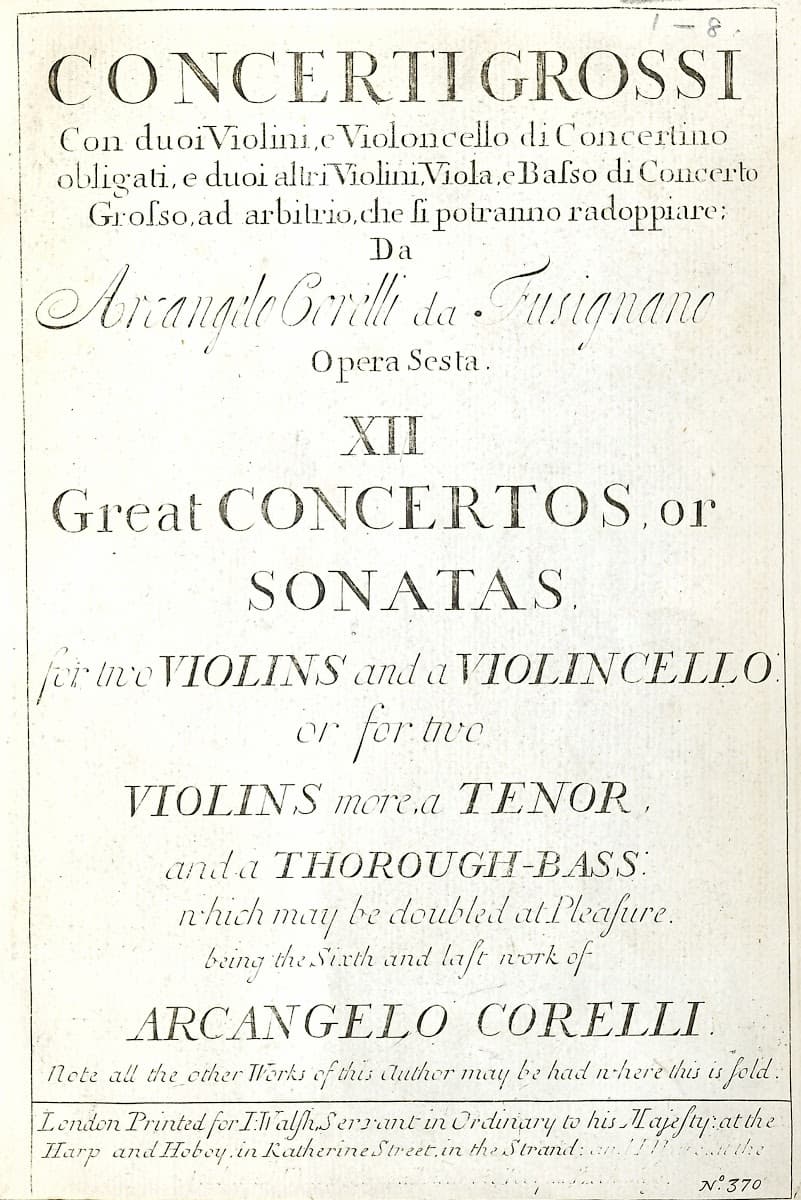

Arcangelo Corelli: Concerto Grosso in F Major, Op. 6, No. 2

Arcangelo Corelli: Concerto Grosso in F Major, Op. 6

The new kind of orchestral music that started to appear towards the turn of the 18th century was called “concerto.” It seems to have been an expansion of the trio sonata, and the “concerto grosso” contrasts a small instrumental group known as the “concertino” with a fuller string orchestra named the “concerto grosso” or “ripieno.” And we find the violinist and composer Arcangelo Corelli (1653-1713) at the forefront of establishing and defining this new and exciting musical genre. His student and lover Matteo Fornari published Corelli’s twelve concerti grossi Op. 6 posthumously. In each of them, the soloist group consists of two violins and a cello, essentially a triple concerto. Since the cello is part of the basso continuo, however, it is sometimes a little difficult to hear the cello as a solo instrument. Corelli didn’t invent the concerto grosso principle, but “he proved the potentialities of the form, popularized it, and wrote the first great music for it.” Without Corelli’s models, many of the subsequent masterpieces might never have been written.

Antonio Vivaldi: Concerto in D minor for two violins and cello, Op. 3, No. 11, RV 565

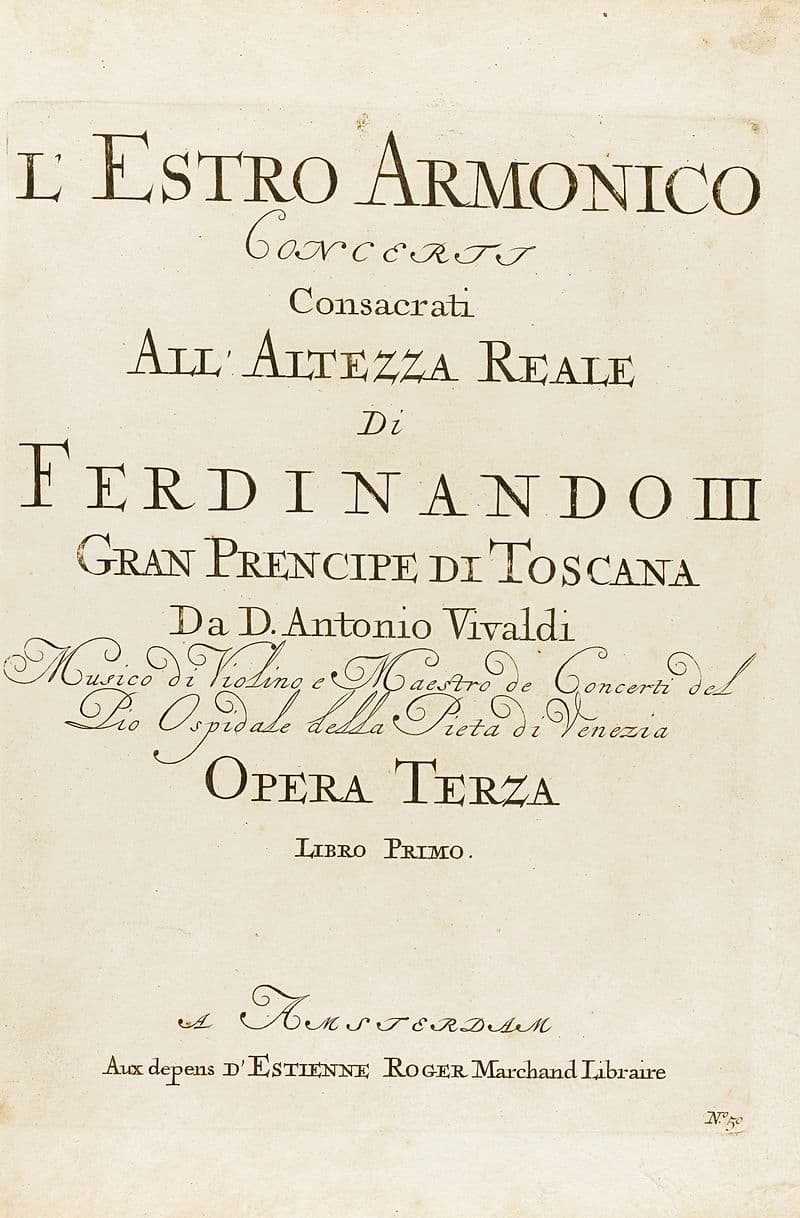

Antonio Vivaldi: Concerto dall’estro armonico first edition

While Corelli was primarily active in Rome, Antonio Vivaldi (1678-1741) lived and worked in Venice. He might not have called his triple concerto for two violins and cello, Op. 3, No. 11 a “concerto grosso,” but he used the exactly same instrumental soloists as Corelli. This triple concerto is part of a set of 12 concertos that Vivaldi published in Amsterdam in 1711. The set is called L’estro armonico (The Harmonic Inspiration) and contains 12 concertos grouped in four cycles of three, “each containing a concerto for 1, 2, and 4 concertante solo violins. Each double violin concerto also had a concertante violoncello part, which did not have a fixed role, sometimes playing solo, sometimes responding to the two violin soloists.” Vivaldi composed a few concertos specifically for L’estro armonico, while other concertos of the set had been composed at an earlier date. Vivaldi scholar Michael Talbot described the set as “perhaps the most influential collection of instrumental music to appear during the whole of the eighteenth century.” After publication, the concertos were widely performed in Italy, and printed copies distributed throughout Europe. Countless arrangements for keyboard instruments in the eighteen-century contributed to the immense popularity of the set.

Georg Friedrich Telemann: Concerto for Flute, Oboe d’amore, Viola d’amore and Strings in E Major

Georg Philipp Telemann

In the first quarter of the 18th century, Georg Philipp Telemann (1681-1767) was considered the greatest living composer besides George Friedrich Handel. To be sure, Telemann was the most prolific composer of his time. As my colleague writes, “Telemann composed a large portion of at least 31 cantata cycles, numerous operas, concertos, oratorios, songs, music for civic occasions and church services, passions, orchestral suites and copious amounts of chamber music. Virtually every major musical style is represented in his output, and in all, he composed well over 3000 works.” So we should really not be surprised to find a number of triple concertos, as Telemann had the outstanding ability to blend the “disparate sounds of the orchestral instruments of his day, giving his concertos their individual character and identifiable colour.” Telemann played most of the instruments for which he composed music, and he knew how to make use of their strong points and avoid their shortcomings. As he writes, “Give each instrument what suits it best, thus is the player content and you well entertained.” Just listen to the triple concerto for flute, oboe d’amore, viola d’amore, and strings, and you know what Telemann is talking about. The three solo instruments are “blended with exceptional skill and artistic sensibility by a composer who clearly understood their every instrumental nuance.” And if you liked this Teleman triple, you will probably enjoy the 16 additional triple concertos he composed.

Georg Philipp Telemann: Concerto for Flute, Oboe d’amore, Viola d’amore and Strings in E Major, TWV 53:E1 (Rachel Brown, flute; Anthony Robson, oboe d’amore; Simon Standage, viola d’amore; Collegium Musicum 90; Simon Standage, cond.)

Johann Sebastian Bach: Brandenburg Concerto No. 5 in D Major, BWV 1050

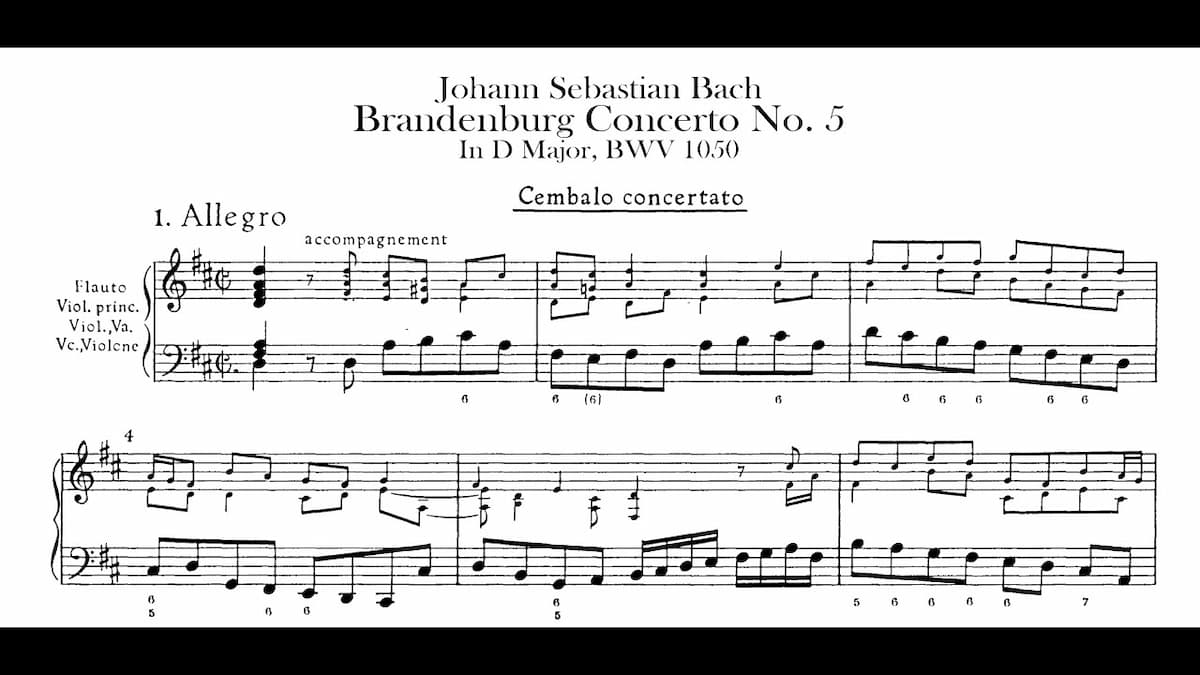

Bach: Brandenburg Concerto No. 5

You didn’t really think that I would forget Johann Sebastian Bach? He composed at least five triple concertos. Two for three harpsichords and string orchestra, the Fourth Brandenburg Concerto for violin and two recorders, a Triple Concerto for violin, flute, and harpsichord, and the Fifth Brandenburg for the same soloists. Bach wasn’t much of a traveler; I suppose his local jobs and plenty of children kept him rather busy. He never met Vivaldi, but only came across his music in 1708 when he was organist in Weimar. His employer was crazy about Vivaldi’s music, and to please Duke Wilhelm Ernst, Bach transcribed at least nine concertos of Vivaldi for solo organ and solo harpsichord. Bach was clearly interested in this new Italian style, and he quickly put Vivaldi’s influence to practical use. Instead of relying on the Corelli model of stringing together a number of short movements of contrasting characters, his Brandenburg Concertos look towards the symmetrical models of Vivaldi. And since Bach was probably the greatest keyboardist of his time, Concerto No. 5 gives special attention to the harpsichord. It is elevated from its usual role to simply support the harmony to a virtuosic position as one of three featured soloists.

Alfredo Casella: Triple Concerto, Op. 56

Casella playing his Triple Concerto

Let’s fast-forward to the 20th century with the Triple Concerto by Alfredo Casella (1883-1947). Casella hailed from the Piedmont region of Italy, and his parents were huge fans of the music of Richard Wagner. His grandfather, father, and uncles were fine cellists, and Casella and his mother were gifted pianists. “Casella made his name in avant-garde pre-First World War Paris, scandalized Rome audiences with his musical iconoclasm, and played a crucial role in establishing orchestral and instrumental music on a more equal footing with Italian opera. In 1938, Casella judged his Triple Concerto, for piano trio and orchestra, as “one of his best pieces.” He singled out the central Adagio as “a type of middle movement without precedent in my work for its great serenity and soft, luminous transparency,” and suggested, “that it reflected the natural loveliness of the landscape around the city of Siena in Tuscany where he composed it in the summer of 1933.”

Alfredo Casella: Triple Concerto, Op. 56 (Mathias Wollong, violin; Danjulo Ishizaka, cello; Frank-Immo Zichner, piano; Berlin Radio Symphony Orchestra; Michael Sanderling, cond.)

Olli Mustonen: Triple Concerto for 3 Violins

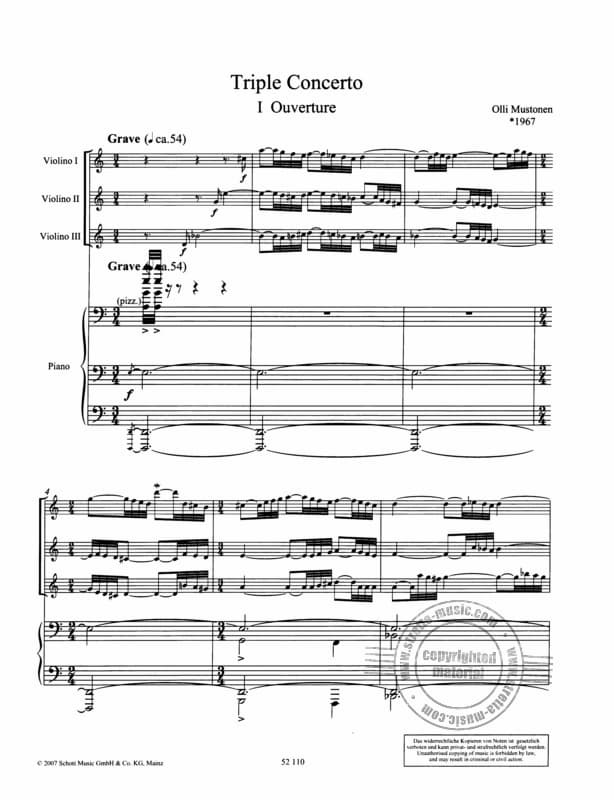

Olli Mustonen: Triple Concerto for 3 Violins

Olli Mustonen describes his Triple Concerto for Three Violins as “a mixture of elements: the mechanics of the Baroque, the looping patterns of Minimalism, and the voluptuousness of Neo-Romanticism.” In fact, Mustonen started his musical career by playing Baroque music on the harpsichord at the age of five. He began to experiment with composition one year later, and started private composition studies at the age of eight with Einojuhani Rautavaara. Mustonen embarked on an international career as a pianist, and “being a performing artist has also helped liberate his creative vein. He has not felt bound by the rules of stylistic schools, or by having to commit himself to dogma and publication schedules.” As a critic writes, “Mustonen’s compositions are the flight of a free and curious spirit, combining a respect for tradition and a high level of craftsmanship with novelty and unpredictability.”

Olli Mustonen: Concerto for 3 Violins (Pekka Kuusisto, violin; Jaakko Kuusisto, violin; Lisa Batiashvili, violin; Tapiola Sinfonietta; Olli Mustonen, cond.)

Bernard Rands: Triple Concerto

Bernard Rands

In the 21st century, we find additional triple concertos by Dmitri Smirnov, Lera Auerbach, and Wolfgang Rihm, and there is also a very exciting triple concerto by Michael Tippet. However, I want to conclude this blog with a Triple Concerto by British composer Bernard Rands. The composer writes that the title, “Triple Concerto,” refers not only to the role of the three soloists (cello, piano, and percussion), but also to that of the orchestra, which is divided into three ensembles, and to the specific relationship of each of the soloists to each of the ensembles. “The three ensembles are grouped around the soloists. The work begins with an extended trio exposition of the musical materials by the three soloists, each of whom then gradually becomes identified with one of the ensembles so that three simultaneous concerti are in progress.” Please do let us know in the comments which other triple concertos you’d like to see featured.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter

Bernard Rands: Triple Concerto (Core Ensemble; Cleveland Chamber Symphony; Edwin London, cond.)

Did Beethoven arrange the triple concerto for three instruments and the piano plays the orchestra part as well.