On 1 July 1925, at the age of 59, Erik Alfred Leslie Satie died in a small apartment in Arcueil, Paris. One hundred years later, at the centenary of his death, his singular creative spirit resonates more loudly than ever.

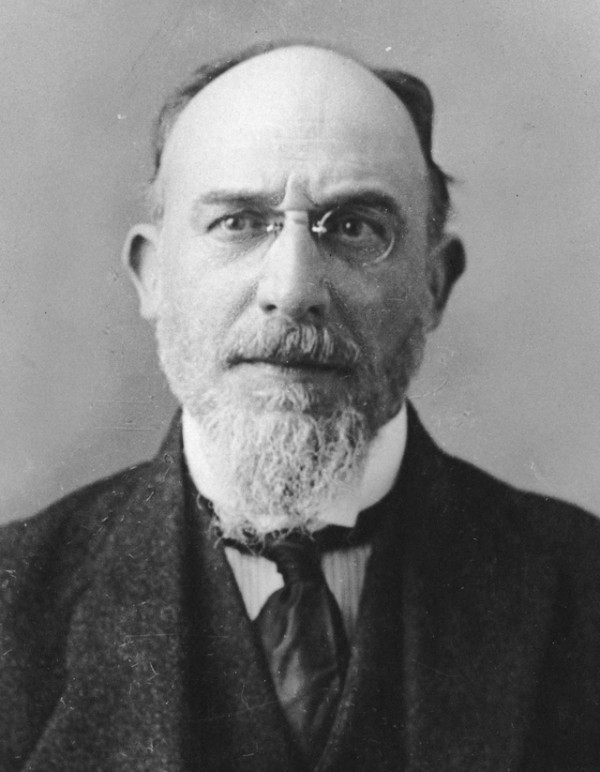

Erik Satie

Satie was, in the words of Debussy, “a gentle medieval musician lost in this century.” He was a paradoxical figure whose sparse, whimsical music and bohemian lifestyle defied convention. Yet, precisely through these eccentricities, Satie became a radical touchstone for virtually every major avant-garde movement of the twentieth century.

On the 100th anniversary of his passing, we commemorate not only the man but the creative insurgency he heralded. Satie rebelled against Romantic sentimentality, subtly mocking its excesses while embracing a visionary simplicity.

Erik Satie: Gymnopédie No.1

From Honfleur to Montmartre

Maisons Satie

Erik Satie was born on 17 May 1866, in Honfleur, France, the eldest child of French father Alfred Satie and British mother Jane Leslie. His early musical education was unremarkable, marked by struggles at the Paris Conservatoire, where he was deemed untalented by his instructors. This lack of recognition fuelled his determination to carve out a distinctive musical voice independent of traditional academic constraints. His early compositions reflected a quiet rebellion, showcasing a simplicity and emotional restraint that contrasted sharply with the prevailing Romantic ideals of his time.

He briefly attempted a military career but absconded by contracting bronchitis intentionally. These early rebellions against academia and the army set the stage for Satie’s lifelong refusal of authority. His defiance of societal expectations extended to his artistic endeavours, where he challenged conventional notions of musical structure and purpose. This nonconformist spirit became a hallmark of his career, endearing him to avant-garde circles and establishing him as a pioneer of musical innovation.

Embracing a bohemian lifestyle, Satie became a pianist at Montmartre’s famed Chat Noir café-cabaret, a place associated with avant-garde artists, poets, and musicians. This environment shaped a unique aesthetic, blending music with satire, absurdity, and the rejection of Romantic excess. The vibrant, irreverent atmosphere of Montmartre inspired Satie to experiment with unconventional forms and playful titles, such as Three Pieces in the Shape of a Pear. His time at Chat Noir not only honed his compositional style but also solidified his reputation as a witty, eccentric figure within Paris’s artistic underworld.

Erik Satie: Gnossienne No. 5

The Music of Simplicity

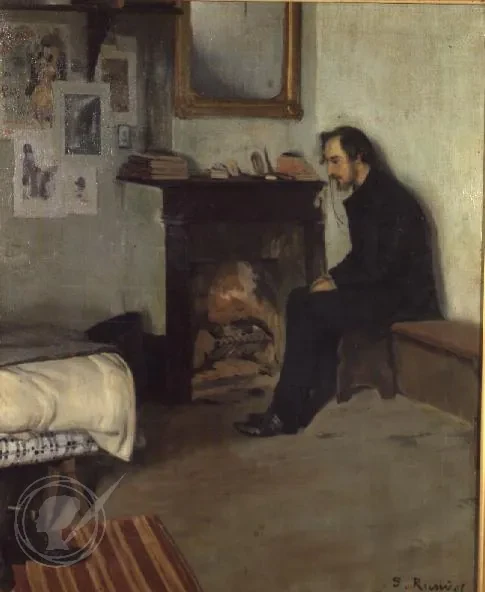

Portrait of Erik Satie in his studio in Montmartre

Satie’s compositions are deceptively simple, yet they carry a profound emotional weight and structural innovation. His Trois Gymnopédies (1888), a set of three piano pieces with sparse, haunting melodies and unadorned harmonies, evoking a sense of timeless serenity, earned them a place in popular culture.

Similarly, Satie’s Gnossiennes (1890–1893) pushed boundaries with their lack of bar lines and ambiguous tonality, creating a dreamlike quality that anticipated minimalist and ambient music. These works exemplify Satie’s ability to distill music to its essence, a principle that would subsequently inspire composers like John Cage and Philip Glass.

Satie’s collaborative work on the ballet Parade (1917), with Jean Cocteau, Pablo Picasso, and Léonide Massine, marked a high point in his career. Premiered by the Ballets Russes, Parade incorporated typewriters, sirens, and other unconventional sounds, shocking audiences with its avant-garde audacity.

It was a “collaborative creation that illuminated Satie’s role as a pioneer of modern aesthetics,” bridging music and visual art while challenging notions of what constituted a musical performance.

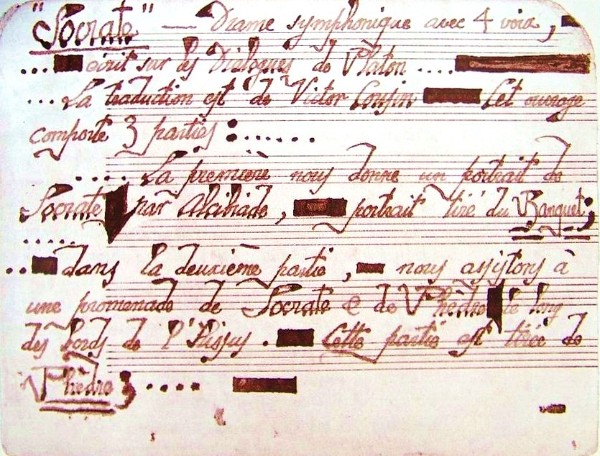

Satie’s Socrate (1918), an oratorio for four sopranos and chamber orchestra, represents his most serious and ambitious work. Based on Plato’s dialogues, it reflects Satie’s fascination with classical ideals and his desire to create music of purity and restraint. As has been noted, Socrate “stands as a testament to Satie’s ability to balance intellectual rigour with emotional depth.”

Erik Satie: Parade

Influence on Modern Music

Erik Satie’s Socrate manuscript

Satie’s influence extends far beyond his lifetime, shaping the course of 20th-century music. His concept of “furniture music,” designed to serve as background ambience rather than the focal point of attention, was revolutionary and paved the way for the background scores of modern media. This innovative idea challenged traditional notions of musical performance, encouraging composers to explore sound as an environmental element rather than a narrative centrepiece.

Satie’s minimalist approach also inspired the repetitive structures of composers like Steve Reich and Philip Glass, who embraced simplicity as a means of exploring new musical possibilities. By stripping music down to its essential components, Satie opened the door for minimalism to flourish as a genre that prioritised texture and rhythm over complex harmonic development. His legacy in this regard continues to resonate in contemporary music, where minimalistic principles underpin diverse styles from ambient to electronic.

Satie rejected Wagnerian grandeur and Romantic excess, writing music that was anti-emotional, anti-virtuosic, and anti-Wagnerian. It certainly offered a counterpoint to the bombast of his contemporaries. This deliberate departure from the prevailing musical trends of his era positioned Satie as a radical voice, advocating for a return to simplicity and irony that resonated with the avant-garde movements of the early 20th century.

His emphasis on clarity and economy influenced the neoclassical movement, particularly composers like Igor Stravinsky and Francis Poulenc, who admired Satie’s wit and precision. And let’s not forget his impact on popular music, as his scores feature in countless films, television shows, and advertisements. Satie’s ability to craft memorable, evocative melodies with minimal means has ensured his music’s enduring presence in both high art and mainstream culture, bridging the gap between the classical and the contemporary.

Erik Satie: Socrate (excerpt)

The Man Behind the Music

Erik Satie

Satie’s life was one continuous act of self-curation. His personality was as unconventional as his music, and he was known for his eccentric habits. He owned dozens of identical grey suits, ate only white food, wrote cryptic annotations in his scores, and founded his own mock religion, the Metropolitan Church of Art of Jesus the Conductor.

Satie’s enigmatic personality has been the subject of much scholarly inquiry. A 2025 study suggests a possible psychopathological underpinning to his eccentricities, such as obsessive-compulsive tendencies and social withdrawal.

Yet, these traits also fuelled his creativity and allowed him to challenge conventions and create music that was uniquely his own. To be sure, his writings reveal a sharp wit and philosophical depth, offering insight into his complex mind.

Satie was clearly a cultural provocateur. His playful titles, such as “Three Pieces in the Shape of a Pear,” and his inclusion of humorous instructions in scores challenged the solemnity of classical music. Scholars describe Satie as an “elusive and endlessly fascinating figure whose work defies categorisation.”

Erik Satie: Vexations (short edit)

Reception and Rediscovery

During his lifetime, many dismissed Satie’s work as mere novelty or frivolity. Critics and musicians alike labelled it “clownish,” “mad,” “trivial,” and unworthy of serious consideration. Satie’s unorthodox approach, however, found a small but devoted audience among avant-garde artists and intellectuals.

He was primarily thought of as a quirky visionary, with Debussy and Ravel recognising his originality. Broader recognition, however, eluded him until after his death in 1925. Rediscovery of his music began in the mid-20th century, as composers and audiences sought an alternative to the dense serialism and academic rigour dominating modern music.

Figures like John Cage championed Satie’s radical simplicity, and a lecture-performance of Vexations in 1948 sparked renewed interest. A couple of decades later, Satie’s works became staples in concert halls and recordings, with artists like Aldo Ciccolini bringing his piano music to new audiences.

Erik Satie: Sports et Divertissements

In Context

As we mark the 100th anniversary of Erik Satie’s death, we are reminded of a composer who stood apart, not through grand gestures, but through quiet subversion. Satie’s music, characterised by its sparseness, wit, and gentle irreverence, challenged the rigid traditions of his time and offered an alternative vision of what music could be. He stripped away ornamentation, resisted seriousness, and infused his compositions with irony and playfulness, making him an outsider in the musical establishment, yet a deeply influential figure for generations to come.

Satie’s enduring relevance lies in his ability to disrupt without alienating, to experiment without losing clarity. He anticipated many of the ideas that would define 20th- and 21st-century music, and artists across genres continue to draw inspiration from his work. His philosophy, as much as his music, endures: a belief in art that is personal, unpretentious, and unafraid to question its own purpose.

In revisiting Satie a century after his passing, we encounter a legacy that resists easy categorization. He was at once austere and absurd, enigmatic and accessible, and a composer who turned simplicity into something radical.

Satie remains strikingly contemporary. His influence is not always obvious, but it is deeply embedded in the artistic fabric of our time. As a composer he foresaw a century of artistic reinvention and helped to make it possible.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up for our E-Newsletter