J.S. Bach

Bach seems so firmly tied to the keyboard that we forget that he was also a master of violin. His initial employment in Weimar was a violinist, eventually rising to the position of concertmaster. His composer sons spoke about their father’s abilities on the violin as being pure and powerful into his old age.

J.S Bach’s Sonata No. 1 for Violin and Harpsichord in B Minor, BWV 1014, is different from many other works for violin and harpsichord because in this score, the right hand of the harpsichord is fully written out. Generally, if the harpsichord is acting as a figured bass instrument, the right hand could take on a more improvisatory character. Only the left hand and the chords to be used were specified, not the action of the right hand. In writing out the right-hand part, Bach is changing the relationship of the instruments: the harpsichord now is equal to the violin, not just its supporter. The harpsichord becomes a second melodic voice as well as being the bass line. One writer described these pieces as being “Trios for two instruments.”

Sonata No. 1 is actually more than a trio. Although it starts like a trio in the first movement, with the melody in parallel thirds and sixth in the right hand of the harpsichord, when the violin enters, we now have 4 voices. Later in the movement, the violin plays in parallel sixths and thirds and so we have 5 voices. It’s an interesting trick that Bach uses to broaden the sound of his small duo into a trio then a quartet and finally a quintet, but all played on 2 instruments.

Ralph Kirkpatrick and Alexander Schneider at Dumbarton Oaks, 1945

Bach returned to these six violin and harpsichord sonatas (BWV 1014-1019) again and again. The original manuscript from around 1717 is lost but a 1725 copy made by Bach’s nephew, Johann Heinrich Bach, shows signs of polishing. A new revision can be found in the 1741 copy made by Johann Friedrich Agricola and yet more revisions in a copy from 1750.

The trio sonata was considered a touchstone of compositional development. Each voice has to hold its own melodically yet, at the same time, be part of a multi-voice structure that has its own integrity.

In the final Allegro movement, the two voices act together to bring us a work that truly exemplifies the best of the Baroque, the best of Bach, and an ideal of composition that was rarely achieved by others.

J.S. Bach: Sonata No. 1 for Violin and Harpsichord in B Minor, BWV 1014 – IV. Allegro

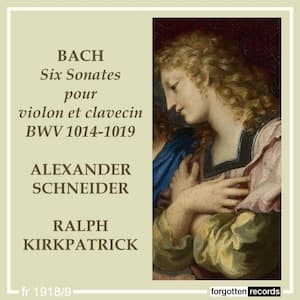

The duo of Alexander Schneider and Ralph Kirkpatrick recorded this Sonata in 1947 at Liederkranz Hall in New York. Lithuanian-born Alexander Schneider (1908-1993) came to the US when on tour with the Budapest String Quartet. They were in the country when WWII began, and they never returned to Germany. Schneider left the quartet in 1944 to make his own career and, after turning down an offer to conduct at the Metropolitan Opera, and offers from the Pro Arte and Paganini Quartets, he began to tour with Ralph Kirkpatrick. He re-joined the Budapest String Quartet in 1956 and worked with them until they disbanded in 1967.

Ralph Kirkpatrick (1911-1984) began to play the piano as a child and continued his piano study while pursuing a degree in art history at Harvard. He discovered the harpsichord while at Harvard and gave his first recital there on the instrument in 1930. When he graduated in 1931, he received a travel fellowship for Europe and studied with the greats of his day: Nadia Boulanger and harpsichord revival pioneer Wanda Landowska in Paris, with Arnold Dolmetsch in England, Heinz Tiessen in Germany and Günther Ramin in Germany. His work on Scarlatti resulted in a biography in 1953 and a critical edition of Scarlatti’s sonatas, known now by their Kirkpatrick numbers. He toured widely with Alexander Schneider and is best known now for his harpsichord recitals of Bach and Scarlatti.

Performed by

Alexander Schneider

Ralph Kirkpatrick

Recorded in 1947

Official Website

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter

I have been obsessed with these works since my early teen years, now going on almost 40 years, and have collected many recordings. Perhaps because they are relatively rarely performed, plus the fact that it is almost easier for the violinist to perform them with harpsichords rather than with piano (zero balance problems with the former), the recordings tend to attract rather unexpected and almost strange combinations of artists: Leonid Kogan/Karl Richter, for example. In addition, these amazing works has attracted rather diverse and, again, unexpected violinists, such as David Oistrakh, and surprising NUMBER of great violinists have recorded them, including Szeryng, Menuhin, Schneiderhan, Laredo, Buswell, and more.

Alexander Schneider/Ralph Kirkpatrick is another unexpected collaboration, and I have not had the pleasure of listening to the recordings. So, I’m rather pleased to see this article which brings attention to not only these works, but this particular recording.

Thank you!

The Adagio of the B Minor Sonata as played by Glenn Gould and Jaime Laredo blows me away.

Gould’s arpeggiations, his spacious, languid tempo and deliberate, literal ornaments create a minimalism that seems almost modern…fresh. Going back to the harpsichord I feel a deeper connection. The piece is enlarged at the same time it is stripped down. Watershed.