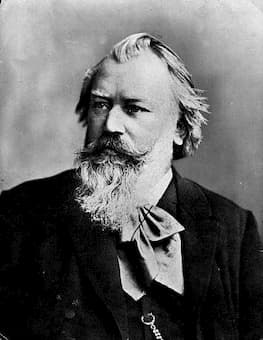

Johannes Brahms (1889)

Johannes Brahms (1833-1897) discovered the music of Hungary through the Hungarian violinist Ede (Eduard) Reményi, who was in Germany after being banned from Austria following his participation in the Hungarian Revolution of 1848. Brahms, 15 at the time of their first meeting, met Reményi again when he returned to Germany several years later and the two toured together. Another Hungarian violinist Brahms met was Joseph Joachim, who became a greater friend and mentor.

The Hungarian Dances, first composed probably in the 1850s were published for piano duet in 1869 (1-10) and 1880 (11-21) and were a great hit for Brahms. The 21 dances were popular and the mode of piano duet was a particular favourite of the time. Eventually, Brahms transcribed Nos. 1, 3, and 10 for orchestra in 1885, Dvořák orchestrated Nos. 17-21, and others did selected numbers as well.

Reutlinger: Joseph Joachim

Joachim did his own transcription of the Hungarian Dances, but this time for violin and piano. Joachim, who had been a protégé of Felix Mendelssohn in Leipzig, made his name with a performance at age 13 of the then-unliked Beethoven Violin Concerto in London. The Concerto had been thought to be a poor kind of work until, in the hands of Joachim, it was recognized as the great piece we now know it to be. He met Brahms when he was 22 years old and Brahms was 20 and unknown. Joachim introduced Brahms to Robert and Clara Schumann and started that life-long friendship.

Joachim’s transcription of the Hungarian Dances created a true violinist’s work – they are not just simple transcriptions of a popular work but are technically challenging for any violinist. They capture the Hungarian spirit and have been called a kind of gypsy “Art of the Violin”. One modern violinist, though, thinks ‘The part is written in a very un-violinistic manner. It is terribly difficult, very high, has many double stops, especially octaves – all that is rather pianistic.’ This may be why, for different recordings, the tempo varies so much, as each violinist copes with both Brahms’ and Joachim’s demands. Dance No. 9, as in common with the first 10 dances, is heavily influenced by the Verbunkos recruiting dance that may be more familiar through its use in Bartók’s clarinet trio Contrasts and in his Violin Concerto No. 2. The verbunkos dance has two sections: a slow (lassú) section with dotted rhythms and a fast (friss) section with running note patterns.

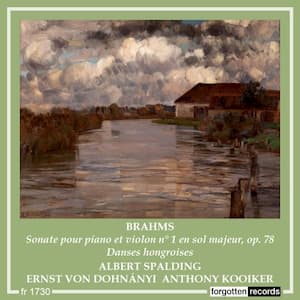

Johannes Brahms: Hungarian Dances No. 9 in E minor (Albert Spalding, violin; Anthony Kooiker, piano)

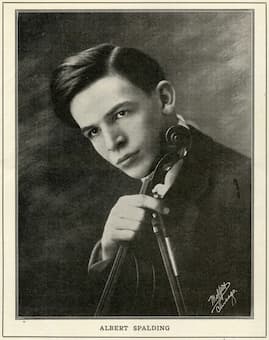

The young Albert Spalding (1911)

In this 1951 performance, violinist Albert Spalding (1888-1953) and pianist Anthony Kooiker, take up the challenge. Spalding, son of the A.C. Spalding sporting goods company co-founder, started his study of the violin young, first in Chicago, then New York, then in Italy, where he graduated from the Bologna Conservatory at age 14. He made his Paris debut at age 18 and his American debut at age 20 with the New York Symphony. He served in intelligence in both WWI and WWII and in 1944, gave a concert for thousands of refugees stranded in a cave during a bombing raid near Naples. After his retirement from the concert stage in 1950, he taught at Boston University’s School of Music, and when it got cold, at Florida State University. Anthony Kooiker (1920-2007) on piano, accompanied Spalding for some four years on tour.

Performed by

Albert Spalding

Anthony Kooiker

Recorded in 1953

Official Website

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter

Beautiful performance.