The Allied initiative to rid German and Austrian society, culture, press, economy, judiciary, and politics of any remnants of National Socialist ideology was launched after the end of the Second World War. The directives of “denazification” identified specific groups and people, and established judicial procedures and guidelines for handling them. In the case of top-ranking Nazis, such as Goering, Hess and Speer, the initiative worked as intended, and all were put on trial for war crimes at the “Nuremberg Trials.” Drawing the lines between resistance, collaboration or passive compliance among Nazi-related organizations, totaling almost 45 million German members, became somewhat more challenging. “All musicians and singers, composers and conductors who had made a living as artist in the Third Reich, emerge in May 1945 severely tainted.” And this included Richard Strauss, Germany’s most prominent composer of his time, who had to justify himself in front of the denazification board. Although he was absolved of any Nazi affiliations, Thomas Mann declared him a “Hitlerian composer.” And Arturo Toscanini famously said, “To Richard Strauss the composer I take off my hat; to Richard Strauss the man I put it on again.” Strauss was fiercely proud of his lack of involvement in politics yet when many important performers fled their homelands rather than cooperate with the Nazi regime, he stayed home and happily composed his music while war waged around him.

The Allied initiative to rid German and Austrian society, culture, press, economy, judiciary, and politics of any remnants of National Socialist ideology was launched after the end of the Second World War. The directives of “denazification” identified specific groups and people, and established judicial procedures and guidelines for handling them. In the case of top-ranking Nazis, such as Goering, Hess and Speer, the initiative worked as intended, and all were put on trial for war crimes at the “Nuremberg Trials.” Drawing the lines between resistance, collaboration or passive compliance among Nazi-related organizations, totaling almost 45 million German members, became somewhat more challenging. “All musicians and singers, composers and conductors who had made a living as artist in the Third Reich, emerge in May 1945 severely tainted.” And this included Richard Strauss, Germany’s most prominent composer of his time, who had to justify himself in front of the denazification board. Although he was absolved of any Nazi affiliations, Thomas Mann declared him a “Hitlerian composer.” And Arturo Toscanini famously said, “To Richard Strauss the composer I take off my hat; to Richard Strauss the man I put it on again.” Strauss was fiercely proud of his lack of involvement in politics yet when many important performers fled their homelands rather than cooperate with the Nazi regime, he stayed home and happily composed his music while war waged around him.

In 1933, when Adolf Hitler became Germany’s chancellor, his propaganda minister Joseph Goebbels founded a specific state department to deal with the arts. Strauss, without being asked, was appointed the first president of the “Reichsmusikkammer (RMK). When he was later asked why he had accepted the appointment, Strauss said, “I hoped that I would be able to do some good and prevent worse misfortunes.” Strauss had to be careful because his daughter-in-law Alice was Jewish, and according to Nazi racial law, so were his grandchildren. He was able to provide some protection—sheltering them in Vienna—but towards the end of the war Alice was arrested. Strauss barely managed to secure her release, and everybody was kept under house arrest in Garmisch until the end of the war. 32 members of Alice’s family, however, were murdered in the Theresienstadt concentration camp!

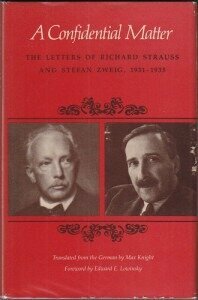

Credit: www.amazon.com

Just a couple of days shy of his 81th birthday, Strauss wrote in his diary in May 1945. “On 12th March even the glorious Vienna Opera became the victim of bombs. But on 1st May ended the most terrible period for mankind – 12 years of the rule of bestiality, ignorance and illiteracy under the greatest of criminals, who brought about the destruction of 2000 years of German civilization.” Strauss was genuinely surprised to encounter a good deal of hostility after the war. A Swiss newspaper publically stated that he was not welcome in the country, a sentiment echoed during his 1947 visit to England. In the end, Strauss, somewhat naively, could never come to terms with the notion that his music and the political situation of his days should be connected in any way, shape or form.

Richard Strauss: Die Schweigsame Frau

Potpourri

Act I: Ei, die Ehre, die Ehre! (Haushalterin, Barbier)