Few characters have captured our imagination than Don Quixote, the befuddled knight—a pathetic, aging oddball who dreams of righting the world’s wrongs. The knight is the protagonist of Miguel Cervantes’ novel Don Quixote or ‘The Ingenious Gentleman Don Quixote of La Mancha’ of 1605, and is considered to be one of the greatest works of fiction ever published. The novel has inspired countless artists to write works based on this story including Richard Strauss who created the magnificent tone poem Don Quixote— subtitled “Fantastic Variations for Large Orchestra on a Theme of Knightly Character“—which features the solo cello as Don Quixote and the solo viola as his sidekick Sancho Panza.

Few characters have captured our imagination than Don Quixote, the befuddled knight—a pathetic, aging oddball who dreams of righting the world’s wrongs. The knight is the protagonist of Miguel Cervantes’ novel Don Quixote or ‘The Ingenious Gentleman Don Quixote of La Mancha’ of 1605, and is considered to be one of the greatest works of fiction ever published. The novel has inspired countless artists to write works based on this story including Richard Strauss who created the magnificent tone poem Don Quixote— subtitled “Fantastic Variations for Large Orchestra on a Theme of Knightly Character“—which features the solo cello as Don Quixote and the solo viola as his sidekick Sancho Panza.

Strauss admitted that his imagination was often inspired by a story. Program music, instrumental music that makes explicit references to episodes in a literary text, was popular but highly controversial in the late-19th century. Critics such as Eduard Hanslick claimed that “pure” or absolute music must be preserved. Programmatic music was “repulsive.” Fortunately for the music lovers among us, Strauss went forward with many programmatic works.

Don Quixote is written in a theme and variations form. We begin with our hero who has lost his sanity after reading too many novels to escape from the hardships of life. “Finally, from so little sleeping and so much reading, his brain dried up and he went completely out of his mind…” (Miguel de Cervantes Don Quixote) Our errant knight is impressively kind and sincere who yearns to redress wrongs, who feels for mothers in mourning, beggars, the oppressed, and for all those who are not loved. Don Quixote is determined to follow his dreams, and to pursue a vision of the world as a better place.

In the first variation, the woodwinds and strings introduce us to the enchantress Dulcinea. Everyone pines for her including Don. The oboe plays an exceptionally exquisite theme, representing Don Quixote’s passionate but chaste love for Dulcinea. Don, determined to win her love, goes out into the world where deceit and man’s inhumanity must be countered.

The cello solo is heroic, full of nobility, grace and gorgeous singing lines. It is quite the tour de force using every inch of the cello and the cellist’s abilities, both technical and emotional. The soloist is required to impersonate this complex characterization—one moment scintillating, the next anguished and agitated, the next befuddled. The lumbering servant’s lines of Sancho Panza in the solo viola are contrasting. He is the buffoon at times and there are many comic interjections by the viola and the bass clarinet and tenor tuba, but his fierce loyalty is never to be questioned.

Strauss invents effects to depict this marvelous story. Don Quixote soon comes across “evil giants”-

“Do you see over yonder, friend Sancho, thirty or forty hulking giants? I intend to do battle with them and slay them.” This is noble, righteous warfare, for it is wonderfully useful to God to have such an evil race wiped from the face of the earth.”

“What giants?” Asked Sancho Panza.

“The ones you can see over there,” answered his master, “with the huge arms, some of which are very nearly two leagues long.”

“Now look, your grace,” said Sancho, “what you see over there aren’t giants, but windmills, and what seems to be arms are just their sails, that go around in the wind and turn the millstone.”

“Obviously,” replied Don Quixote, “you don’t know much about adventures.”

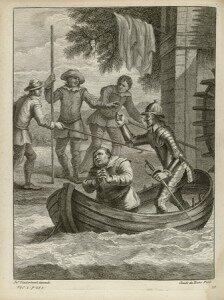

Don Quixote – The Journey in the Enchanted Boat

Strauss stretches the instrumentalists deploying unconventional techniques. As a result, the sounds and textures are distinctive. In the second variation, for example, Don Quixote encounters a herd of sheep and thinks they are a dangerous approaching army. Strauss depicts bleating of sheep using a technique in the brass called flutter-tonguing. It really sounds like the horns are braying! In variation VII our heroes ride on an imaginary flying horse evoked by a wind machine.

In the eighth variation, our adventurers have been thrown overboard during a voyage on a boat. They are thrust toward dangerous watermills. At the last minute millers save them. The strings play pizzicato (plucking) to imitate water droplets falling from their soaked clothes.

Just prior to the ending we hear a pounding timpani playing an inexorable rhythm. We feel doom approaching but the emerging sun interrupts. One of the most ravishing cello solos of the entire literature follows. During the Finale, despite the intangibility and ephemerality of truth, Don Quixote accepts his fate peacefully, reminding us that our imaginations can never be taken from us, that good actions ennoble us. Don Quixote dies clinging to his hope for humanity. The solo cello takes a last quiver sliding slowly down the lowest string of the cello, the “C” string that virtually disappears lonely and alone.

Strauss’ tone poem of 1897 was written for the orchestra’s principal cello to perform from his or her seat within the orchestra, but well-known soloists often play it. I think it is one of the greatest solo cello works of the literature. Recordings include illustrious cellists Emanuel Feuermann, Mstislav Rostropovich, Gregor Piatigorsky, Janos Starker and more recently Yo Yo Ma.

Don Quixote is a metaphor for our own struggles in life. It is wonderful to play as well as to listen to and the cello is exquisitely suited to depict this 400-year-old character that continues to touch our hearts and inspire us toward making this truly a better world.

“Too much sanity may be madness. And maddest of all, to see life as it is and not as it should be.”

Richard Strauss: Don Quixote op. 35 (1897)