Triumph of Music

Here is your pop quiz for today! Who said, “There is nothing on earth that approaches the perfection of The Magic Flute and the Bible”? I give you a hint; his paintings are rendered with an extraordinary formal inventiveness, vivid colors, and deceptive fairy-tale naïveté. He is also credited with synthesizing the art forms of Cubism, Symbolism, and Fauvism, and he is considered the “quintessential Jewish artist of the twentieth century.” The answer, and I am sure you have guessed it by now, is Marc Chagall. He was born on 7/7/1887 in the city of Vitebsk, currently located in Belarus, as the first child of his sixteen-year old mother Feige-Ite and her poor working-class husband Khatskl. But there was a problem as Moyshe Shagal — he changed his name after immigrating to France — was born dead! “Imagine,” he writes in his autobiography, “a pale bladder that doesn’t want to live in this world! They threw me into a trough filled with cold water and revived me, so when I opened my eyes, the first thing I saw was a trough. But what’s important is that I was born dead.” Chagall certainly wasted no time celebrating the gift of life, and for the next ninety-eight years he was driven by an incessant urge to create. And he tirelessly created works in virtually every artistic medium, ranging from book illustrations, stained glass, stage sets, ceramic, tapestries, fine-art prints, and of course paintings.

Sources of Music

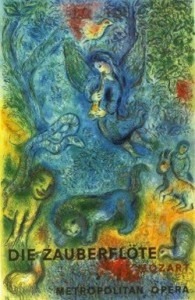

Yet it may surprise you that in his childhood he desperately wished to become a singer or a violinist. Over time, he developed a feverish love for classical music, and simply would not paint without listening to a bit of Mozart. When the Metropolitan Opera in New York commissioned Chagall to design the stage sets and costumes for its first production of Mozart’s Magic Flute — he had previously designed the sets and costumes for Igor Stravinsky’s The Firebird and Maurice Ravel’s Daphnis and Chloë — he immediately agreed. Over three years he created 13 large and 26 small curtains, and 121 costumes and masks. In addition, he also completed two monumental murals — currently housed outside the Met — entitled The Sources of Music and The Triumph of Music. Chagall described his work in the following way: “I paint demons, grotesque little animals, all sorts of unreal creatures I have invented. They are symbols, masks to conceal the sordid faces of the world, eliminating and shutting out what is evil. I focus on gladness and joy. I use my art as eyeglasses through which I can see only what is good and beautiful and true. I offer my art as spectacles to others, so they also can see my vision of the world, the joy of living. Mozart did the same thing.”

Chagall Magic Flute

The Triumph of Music, organized around a series of spirals is somewhat abstract in its reference, as it transforms the conventional references of classical mythology “into the personal mythology of Chagall.” He not only pays homage to American, Russian and French Music, but also depicts himself and his wife next to the blue tree. We also find the customary angels, birds, floating violins and other biblical and musical motifs. The centrally placed Orpheus and his lute, on the other hand, dominates The Sources of Music. New York cityscapes intermingle with the “Firebird” and a group of figures on the left-hand side of the mural. This group, corresponding to the main figures from the narrative of Mozart’s Singspiel embedded within a Garden of Eden scene, appears in the poster Chagall excerpted for the 1966 Magic Flute production. A recent study has suggested that, “everything points to a deliberate attempt by Chagall to draw parallels between The Magic Flute and the Bible, since he felt that both works shared fundamental principles of goodness and truth.

Marc Chagall

Each figure on the poster can be identified as a character from the opera while simultaneously corresponding to a character from the Garden of Eden.” Five distinct figures inhabit the poster: a large snake guard two feline creatures resembling a pair of lions, while a bird with an abstracted triangular tail crowns the mysterious flute-playing figure. One is immediately reminded of Act 1, Scene 3 of the Magic Flute, when Tamino plays his enchanted flute, which in turn lures the forest animals out to dance. However, an alternate interpretation suggests that, “these creatures actually represent four key figures from Mozart’s opera symbolically disguised as animals. The winged figures stand for the Queen of the Night, while the snake represents the serpent-like creature chasing Tamino in the first scene of the opera. The pair of lions is meant to symbolize Tamino and Pamina, and Sarastro is embodied in the white bird above.” Simultaneously, the connection to the Garden of Eden is plainly evident.

Paris Opera Ceiling

For Chagall, “the Bible has always seemed to me and still seems today the greatest source of poetry of all time.” The poster contains the essential elements of the Garden of Eden story. The pair of amorous lions represents Adam and Eve, while the infamous biblical symbol of evil is simultaneously represented by the snake and the Queen of the Night. They are placed as a physical barrier between humanity and the dove, a common symbol of the presence of god. Its triadic tale surely derives from the Masonic symbol of the “Eye of Providence,” also know as the all-seeing eye of God. In his Magic Flute poster, Chagall not only reveals his profound reverence for Mozart and the Bible, but he “managed to reconcile them harmoniously, in humanistic fashion, in a pictorial allegory of good and evil.” Four years earlier, Chagall was commissioned to paint the new ceiling for the Paris opera, and he colorfully paid tribute to Mozart, Wagner, Mussorgsky, Berlioz and Ravel alongside famous actors and dancers; I’ll tell you about that composition at a later time.