When the 16-year-old Swiss craftsman Burkat Shudi made his way to London in 1718, he could scarcely have imagined that he would play a pivotal role in the development of the modern piano. Initially, Shudi established a company that produced harpsichords, and on his first visit to London, the nine-year-old Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart performed on a Shudi instrument.

When the 16-year-old Swiss craftsman Burkat Shudi made his way to London in 1718, he could scarcely have imagined that he would play a pivotal role in the development of the modern piano. Initially, Shudi established a company that produced harpsichords, and on his first visit to London, the nine-year-old Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart performed on a Shudi instrument.

By 1761, Shudi was joined by the Scottish cabinetmaker John Broadwood, who eventually married Shudi’s younger daughter and became a partner in the firm in 1770. By then, Bartolomeo Cristofori’s invention — the Pianoforte — had become one of the hottest musical tickets in Europe. Inspired by German instrument makers, the Shudi/Broadwood workshop produced its first square piano — an instrument that has horizontal strings arranged diagonally across a rectangular case — in 1771. Broadwood continued to improve his instruments, quickly patenting the “under damper,” a felt damper uniquely located below the strings, and he also registered the “English double action,” a mechanism that allowed a note to be replayed without the key being fully released. The changing of the times is clearly evident in Broadwood’s sales records. In 1784, for example, Broadwood sold 133 pianos, but only 38 harpsichords. By focusing on his piano production Broadwood was able to significantly improve his new best seller. In collaboration with the touring virtuoso Jan Ladislav Dussek, the Broadwood grand piano first extended its range beyond five octaves, and later beyond six. Dussek was soon joined by Muzio Clementi — who had established his own piano factory — and John Field, who contributed significantly to the development of a distinctive “London School” of pianoforte compositions, taking advantage of the superior tone qualities and extended range of the Broadwood piano.

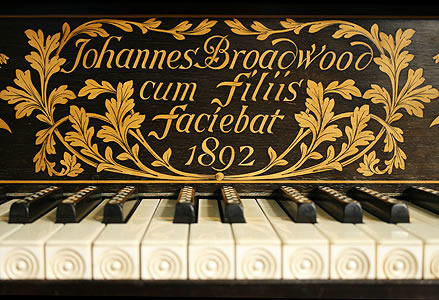

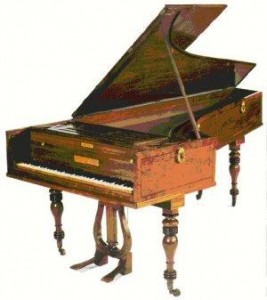

Trying to expand business after the Napoleonic Wars, the next generation Broadwood visited Beethoven in Vienna, and on 27 December 1817 made the following entry in the Broadwood records: “Taken today from our London warehouse, a 6-octave grande pianoforte, number 7362, tin and deal case. Beneficiary: Mr. Ludwig van Beethoven, master composer of music in Vienna. To be shipped to his current residence at Mödling, near Vienna Austria, via Trieste.” When Beethoven learned of the intended gift, he wrote a glowing letter to Thomas Broadwood on 7 February 1818. “I have never felt a greater pleasure than you honour’s intimation of the arrival of this piano, with which you are honouring me as a present. I shall look upon it as an altar upon which I shall place the most beautiful offerings of my spirit to the divine Apollo. As soon as I receive your excellent instrument, I shall immediately send you the fruits of the first moments of inspiration….” Thomas Broadwood had the name BEETHOVEN inlaid in ebony above the keys, and the instrument stayed in the composer’s possession until his death in 1827. It was then purchased by the Viennese music publisher C. Anton Spina, and presented to Franz Liszt who kept it in his home in Weimar. The instrument can still be viewed in the National Museum of Hungary, in Budapest.

Trying to expand business after the Napoleonic Wars, the next generation Broadwood visited Beethoven in Vienna, and on 27 December 1817 made the following entry in the Broadwood records: “Taken today from our London warehouse, a 6-octave grande pianoforte, number 7362, tin and deal case. Beneficiary: Mr. Ludwig van Beethoven, master composer of music in Vienna. To be shipped to his current residence at Mödling, near Vienna Austria, via Trieste.” When Beethoven learned of the intended gift, he wrote a glowing letter to Thomas Broadwood on 7 February 1818. “I have never felt a greater pleasure than you honour’s intimation of the arrival of this piano, with which you are honouring me as a present. I shall look upon it as an altar upon which I shall place the most beautiful offerings of my spirit to the divine Apollo. As soon as I receive your excellent instrument, I shall immediately send you the fruits of the first moments of inspiration….” Thomas Broadwood had the name BEETHOVEN inlaid in ebony above the keys, and the instrument stayed in the composer’s possession until his death in 1827. It was then purchased by the Viennese music publisher C. Anton Spina, and presented to Franz Liszt who kept it in his home in Weimar. The instrument can still be viewed in the National Museum of Hungary, in Budapest.

By 1842 Broadwood produced roughly 2500 pianos a year—everything from uprights to Concert Grands—and their company provided an instrument for Frederic Chopin’s 1848 concert tour of the British Isles. “Broadwood, who is a real London Pleyel,” Chopin writes, “has been my best and truest friend. He is as you know a very rich and well educated man with splendid connections.” When Liszt made his final London appearance in 1886, an event described by the Musical Times as “a visit that has been something more than a nine day wonder,” he predictably performed on a Broadwood piano.

Broadwood is still going strong in 2013, and the company rightfully describes itself as “the oldest established piano manufacturer in the World today.” An interesting fact aside, during the years of World War I, the Broadwood piano factory was turned into an aircraft assemblage facility, and it was rumored that piano wires held the early bi-planes of the British Air force together. Truth is, they actually did!

Beethoven Piano by Broadwood

More Society

-

Will Trump’s Tariffs Destroy Music Education in America? We look at how the trade war matters to beginning students and more

Will Trump’s Tariffs Destroy Music Education in America? We look at how the trade war matters to beginning students and more -

Forbidden Harmonies: Composers Whose Music Was Once Banned Discover these stories of musical resistance

Forbidden Harmonies: Composers Whose Music Was Once Banned Discover these stories of musical resistance -

Nixon in China February 21, 1972: 'The week that changed the world'

Nixon in China February 21, 1972: 'The week that changed the world' -

Manchester Camerata to Host the UK’s First Centre of Excellence for Music and Dementia "It's really changed how we view music and what it can do for people"

Manchester Camerata to Host the UK’s First Centre of Excellence for Music and Dementia "It's really changed how we view music and what it can do for people"