Theodor Leschetizky

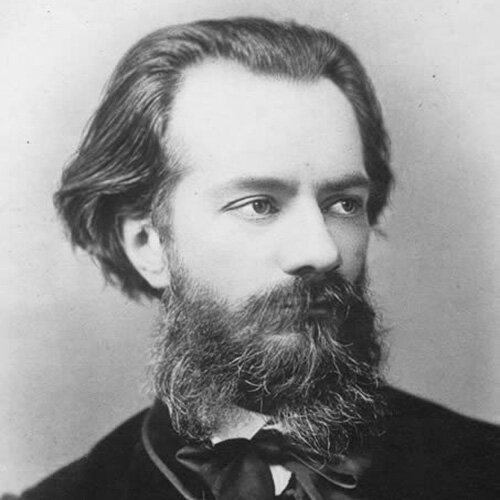

What made Theodor Leschetizky one of the most impressive piano pedagogues of all time? Supposedly, his success was based on the so-called “Leschetizky Method,” a method of instruction that relied on several distinct influences. As part of an unbroken chain of pedagogical lineage, Leschetizky became a student of Carl Czerny, himself a student of Beethoven. As a teacher, Czerny is said to have promoted “accuracy, brilliancy, and pianistic effects in order to achieve a certain freedom of delivery and depth of feeling.” Czerny also instilled in Leschetizky a great love for the compositions of Beethoven, which in turn, shaped his personal interpretations and pedagogy.

Carl Czerny, 1833

Leschetizky described Czerny’s as an “orchestral director; he was dynamic, outspoken and often used gestures as a way of communicating slight variations in tempo and tone color.” In terms of repertory, Leschetizky focused on the music of Beethoven, but in the 1840s he heard a performance by the Bohemian composer and pianist Julius Schulhoff. That experience completely changed his ideas about playing the piano. He writes, “Under his hands the piano seemed like another instrument. Seated in a corner, my heart overflowing with indescribable emotions as I listened. Not a note escaped me. I began to foresee a new style of playing. That melody standing out in bold relief, that wonderful sonority; all this must be due to a new and entirely different touch. And that cantabile, a legato such as I had not dreamed possible on the piano, a human voice rising above the sustaining harmonies.”

Theodor Leschetizky: Contes de Jeunesse Suite, Op. 46 (Peter Ritzen, piano)

Julius Schulhoff

The impact of having heard Schulhoff play in Vienna led Leschetizky to pay special attention to tone quality, both in his playing and his teaching. A scholar writes, “Leschetizky realized that while there are certain technical elements necessary in the manufacturing of tone production (firm finger tips, flexible wrist), his was not a search for the perfect finger, but for a much greater ideology.” Putting his initial pedagogical ideas into practice during his time in Russia, Leschetizky soon attracted more students than he could possibly teach himself. As such, he deputized his own students to become preparatory teachers conveying the technical and musical fundamentals of pianism. This system became an integral part of his teaching studio, as he believed “it advantageous for both teacher and student. The preparatory teacher and the master operate on equal footing, and in a system that encouraged candid questioning without the element of fear.”

Theodor Leschetizky: 2 Arabesques for Piano, Op. 45, No. 1 Arabesque en forme d’Etude (Theodor Leschetizky, piano)

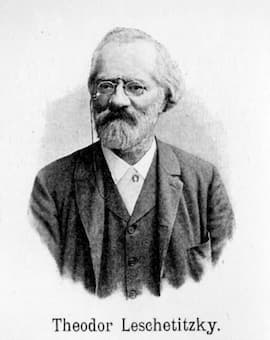

Malwine Bree

Theodore Leschetizky learned from Carl Czerny the importance of a historical tradition in terms of musical interpretation and pedagogical lineage. From Julius Schulhoff he gained knowledge of tone production and pianistic effects and sonorities, and the third primary influence on what is known as the “Leschetizky method” originates in his engagement with the “Ton-Künstler Verein” in Vienna. That musical society consisted of performers, composers, philosophers and intellectuals espousing a humanistic ideal “in which all art forms are intertwined and the circulation of knowledge involves both the giving and receiving of information.” Leschetizky insisted that a specific schedule of technical training did not exist, as he primarily taught highly advanced students. The legend of a dedicated “Leschetizky Method” was primarily advanced by his assistants. Most authoritative among them is “The Groundwork of the Leschetizky Method” published by Malwine Bree in 1902, one of his St. Petersburg students who followed him to Vienna. This publication laid the basis for attracted hundreds of students from all corners of the world, and Leschetizky was predictably happy to endorse the book.

Theodor Leschetizky: Pastels, Op. 44 (Tobias Bigger, piano)

The Leschetizky Method

As a teacher, Leschetizky was “patient, sincere and did not tolerate sadness of frivolity.” Always interested in the aesthetic of beauty, he espoused a heightened sense of perception and musical insight. He did demand utter devotion and loyalty from his students, and believed that “a solid work ethic constituted one of the primary indicators of success.” Leschetizky always considered his students as part of his immediate family. “He was more than a teacher, more akin to a mentor, therapist, father-figure, sponsor and general caretaker.” As has been written, “his most prominent quality was his extreme interest in the well-being of his students.” His principle goal was for his students to mature into well-rounded artists and people. “In order to become successful in music,” he remarked, “one must also be successful in other matters of life.” The “Leschetizky Method,” in essence, is a holistic approach to piano pedagogy and life, and not a technical primer. And while we might consider his emotional attachments to his students as inappropriate, Leschetizky’s success is based on his determination to “teach the mind, the soul, and the fingers.”

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter

Theodor Leschetizky: 2 Pieces for Piano, Op. 2, No. 1 “Les Doux Alouettes” (Clara Park, piano)