Having been born, raised and educated in rural Austria ill prepared Anton Bruckner (1824-1896) for the acidic and highly competitive musical environment of imperial Vienna. Retaining his shy and unassuming demeanor throughout his life, Bruckner presented a wide target for music critics, journalists and composers alike, with most famously perhaps, Johannes Brahms referring to him as a “country pumpkin.” Much of this deep-seated resentment focused on Bruckner’s total admiration for Richard Wagner and a highly idiosyncratic and expansive musical style. The reaction to his Symphony No. 6, partially completed in 1881, was predictably swift and severe. The music critic Eduard Hanslick—a close personal friend of Johannes Brahms—perceived “a clever and original work in which inspired moments alternate frequently without recognizable connections; full of barely understandable platitudes, and empty and dull patches that stretch to unsparing lengths.” It’s not surprising that Bruckner was prone to suffer from debilitating insecurities that made him revise his works multiple times.

Having been born, raised and educated in rural Austria ill prepared Anton Bruckner (1824-1896) for the acidic and highly competitive musical environment of imperial Vienna. Retaining his shy and unassuming demeanor throughout his life, Bruckner presented a wide target for music critics, journalists and composers alike, with most famously perhaps, Johannes Brahms referring to him as a “country pumpkin.” Much of this deep-seated resentment focused on Bruckner’s total admiration for Richard Wagner and a highly idiosyncratic and expansive musical style. The reaction to his Symphony No. 6, partially completed in 1881, was predictably swift and severe. The music critic Eduard Hanslick—a close personal friend of Johannes Brahms—perceived “a clever and original work in which inspired moments alternate frequently without recognizable connections; full of barely understandable platitudes, and empty and dull patches that stretch to unsparing lengths.” It’s not surprising that Bruckner was prone to suffer from debilitating insecurities that made him revise his works multiple times.

But Bruckner had other problems as well! For one, he had a compulsion to count things continually. In medical terms, this is called “numeromania” and professionally classified under compulsive disorders. He obsessively counted windows of building, cobblestones on the road, and number of bricks in a wall. Even worse, he continually counted the number of bars in his enormous orchestral scores to make sure their proportions were statistically correct. He once even tipped a conductor with cash for getting through a rehearsal of one of his symphonies. In his diaries, he kept long lists of teenage girls he fancied, and to their surprise, frequently propositioned them. All his life, Bruckner was fascinated with death. For one, when his mother died, Bruckner commissioned a photograph of her corpse, and kept it in his teaching room. He did not have a single image of his mother when she was alive, just the eyes of the dead woman staring at him and his students.

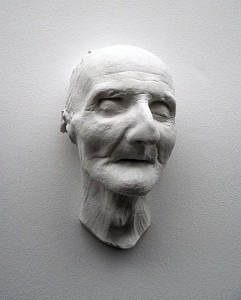

Bruckner eventually developed an obsession with viewing dead bodies. He became a frequent visitor at funeral parlors and in cemeteries, viewing the bodily remains of total strangers. He sought permission to exhume and see the body of his dead cousin, a request that was refused by local authorities. Bruckner even applied to see the corpse of Emperor Maximilian, whose body had been returned to Vienna after his execution in Mexico in 1867. When the remains of Beethoven and Schubert were moved to Vienna’s Central Cemetery in 1888, Bruckner just had to be there. Eyewitness accounts recall that Bruckner “fingered and kissed the skulls of both composers.” Given Bruckner’s obsession with death, it is hardly surprising that he gave very specific instructions on how to deal with his own dead body.

On 11 October 1896, Anton Bruckner died at age 72 in Vienna. His body was initially released for viewing at the St. Charles Church in Vienna, and five days later arrived at the St. Florian Monastery in his hometown of Linz. Between the viewing in Vienna and the burial in Linz, a certain Professor Paltauf mummified Bruckner’s body, just as the composer had specified in his will! In 1996, in preparations for the Bruckner centenary celebrations, it was discovered that the Mummy had begun to decay. As such, the Monastery arranged for the Mummy to take a secret restoration trip to Switzerland. Restored in body and clothing, Bruckner returned to Linz and officials pronounced the result “like he died yesterday.” Bruckner’s obsessions and compulsions left traces in his compositions. You just have to listen to the chilling and dehumanized orchestral landscape in the final movement of his 4th symphony, or the emotional desolation of the slow movement of his 7th. And don’t forget the aggressive, apocalyptic and despairing visions of cosmic pain in the third movement of his unfinished 9th symphony!

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter

Anton Bruckner: Symphony No. 9 – III. Adagio: Langsam feierlich (Carlo Maria Giulini, cond.; Stuttgart Radio Symphony Orchestra)

Fascinating. I would love to know the sources for his morbid fascination with death. He is my personal favourite in that his music both relaxes me and fills me with tension. Rest in eternal peace Anton

Largely paraphrased from an article written for the Guardian in April 2014, but a bit more succinct and shorter, arguably making it an easier read than Tom Service’s more in-depth analysis. But if you’d like a more discerning look at the man who, in life, was more fascinated with death, check out this article: https://www.theguardian.com/music/2014/apr/01/sex-death-dissonance-anton-bruckner-concertgebouw-orchestra

It also explores his reputation as a stodgy, cranky yokel whose adherence to what was viewed as outdated and rigid rules in a musically progressive scene at the time made him a laughingstock. The man was not exactly shrouded in mystery, as he was very open about his oddity. But his oddity is fascinating nonetheless, and it takes an undoubted amount of creativity to construct the sort of sounds you hear in his music, while he adheres so strictly to old rules. Just goes to show what some perceive as limitations, others, such as Bruckner, perceive merely as challenges to be overcome. Very interesting (though undoubtedly creepy) man.

Those interesting in learning about Bruckner would benefit from reading the short biography by Hans Hubert Schoeznler who says the photograph of Bruckner’s mother was hidden behind a curtain, not on display.

Death was part of Bruckner’s life: when young, he played music at funerals, including that of his father, who died at age 47.

Taking photographs of the deceased was quite common in the 19thC, where death was more common and less alien than it seems to be to many people nowadays.

Providing context would be useful for an understanding of Bruckner. However it does not appear to suit the agenda of Service or Predota.

Thank you! was concered something was missing, also in The Guardian article, just to make it more shocking, thats sad

Thank you for some much-needed perspective. Enough selective presentation of facts can create genuine misrepresentation.

Thank you

His music is sublime. I suppose in different ways many of the great composers were eccentric, maybe part of their creativity.

I walk my sister’s dog 4-5x’s day a week in the afternoon. Listening to Bruckner is, by far, my favorite music for the walks. I was also interested to learn that he had OCD. I have some myself. No wonder I enjoy his music so much!