Friedrich Hebbel

Friedrich Hebbel wrote his poem “Schön Hedwig” in 1838 as a protest reaction against “Griseldis,” a play in blank verse by Friedrich Halm that enjoyed huge success in Vienna. Halm’s play is set in Arthurian England, with the eponymous heroine leaving her husband Sir Perceval when she discovers that the trials she has undergone have been cruelly unnecessary. “This theme of independent womanhood in conflict with itself was repugnant to Hebbel.”

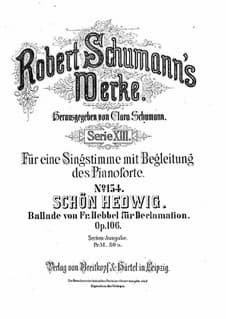

Robert Schumann: Schön Hedwig

In Hebbel’s poem, a gallant knight of yore chooses his fair lady and marries her. She is an illegitimate foundling, and it is within the power of the knight to respond to his instincts concerning her goodness, and to sweep the shame of her birth aside before elevating her to the highest rank in the land. It certainly is paternalistic, but Hedwig is no princess in disguise to preserve the status quo. The poem has twelve strophes, and Robert Schumann confided in his diary “it would be a good idea to arrange this poem for narration and piano.” He musically frames the poem with a long piano prelude, and when the knight asks Hedwig outright whether she loves him “the narrator’s voice is accompanied by solemn yet lyrical music.” When Hedwig eventually admits in public to loving her master, she believes that she must enter a nunnery. However, Schumann quickly allows the knight to sweep the astonished girl away in his arms and to marry her straightaway in the chapel.

Robert Schumann: Schön Hedwig, Op. 106 (Declamation) (Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau, narrator; Daniel Levy, piano)

Walter Braunfels

Critics have suggested that the music of Walter Braunfels (1882-1954) died twice. Once when the Nazis declared his music “degenerate art,” because it did not fit the Third Reich’s narrow aesthetic and racial prescriptions. Modernism was not just an inferior or distasteful style, but a swindle and dangerous lie perpetuated by Jews, communists, and the insane to contaminate the body of German society. In post-war Germany, Braunfels was shunned again as the various schools of tonal music, and specifically romantic music was tainted and seen as corrupt. We should not forget however, that Braunfels was the second most performed opera composer in Germany after Richard Strauss, between the wars. In fact, the Mozart biographer Alfred Einstein wrote, “I do not believe such complete works of art have ever before been performed on the German operatic stage.” In the Lied genre, Braunfels wrote harmonically complex and occasionally uncompromising works. However, in Hebbel’s “To a young girl,” we find a composer of romantic disposition and delightful irony.

Walter Braunfels: 6 Gesänge, Op. 4, No. 3 “An ein junges Mädchen” (Konrad Jarnot, baritone; Eric Schneider, piano)

Johannes Brahms, c. 1872

Lieder accompanied Johannes Brahms throughout his life. Brahms composed his songs independently from one another, grouping them together only later for publishing. He carefully determined their order within an opus, and he was greatly irritated when singers did not adhere to this ordering and changed them according to their mood or form on the day. Brahms Lieder are closely bound to specific performers and instruments, such as the J.B. Streicher piano, No. 7243, which he preferred to play at his home. He wrote, “It is a very different thing to write for instruments whose characteristics and sound you only have incidentally in your head and which you can only mentally hear, than to write for instruments you know through and through, as I know this piano. With this one I always know exactly what I am writing and why I am writing in one way or another.” Published in 1871, his Op. 58 contains two songs by Friedrich Hebbel, which contribute an unusual array of moods and styles within a carefully planned organization.

I look down into the lane:

Over there, she used to live;

That empty deserted window,

How brightly does the moon shine on it!

There is so much else to illuminate;

Oh lovely beams of light,

Why then weave so eerily

Around this place of nothingness.

Johannes Brahms: 8 Lieder und Gesänge, Op. 58, No. 6 “In der Gasse” (Ulf Bästlein, baritone; Sascha el Mouissi, piano)

Richard Stöhr, 1910

Richard Stern (1874-1967) was born in the same year as Arnold Schoenberg. His father was professor of medicine at the University of Vienna, and his mother was the sister of Heinrich Porges, one of Richard Wagner’s closest associates. Stern did obtain a degree in medicine in 1898, but he immediately entered the Vienna Academy of music. In the very same year he converted to Christianity and changed his name to Stöhr. He entered in his diary, “This was the year the big change occurred. Herewith I have sealed the fate of my future life. Now I am a musician and I carry this responsibility seriously, consciously and without regret. At the same time came the actual change of my name to ‘Stöhr,’ on which I had decided already in the summer. It was just the right time for this and I am glad I didn’t miss it. I am certain that in the future advantages will come from this for me.” Stöhr did become a full professor at the Academy in Vienna, and his compositions show real craftsmanship and imagination. His setting of Hebbel’s “Prayer” includes the cello, allowing the composer the opportunity for additional word painting.

You who rise upward beyond the stars

With the emptied bowl,

In order to fill it anew with haste

the eternal wellspring,

Shake it just once more, oh Fortune,

Once more, smiling goddess!…..

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter

Richard Stöhr: 3 Songs, Op. 21, No. 1“Gebet” (Seth Keeton, bass-baritone; Stefan Koch, cello; Mary Siciliano, piano)