Friedrich Hebbel

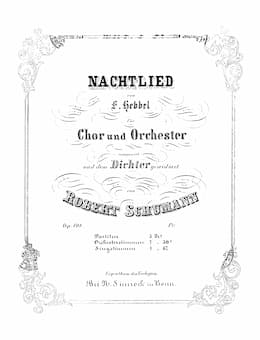

Robert Schumann had a face-to-face encounter with Friedrich Hebbel in 1847. Hebbel had called on Schumann in Dresden while passing through. Hebbel found Schumann “not only persistently, but also uncomfortably mute.” Schumann, as he noted in his diary, however, felt deeply honored by the visit. Two years later Schumann set Hebbel’s Nachtlied (Night Song) for eight-part choir and orchestra in a matter of days. The twelve lines of poetry portray the transition from the waking state to sleep as if it were a mysterious alternate world.

Schumann: Nachtlied

Rising and burgeoning night,

full of lights and stars;

in the eternal far-away distance

tell us: what has been awakened?

Heart and chest are tightening,

ascending, declining life;

I feel its gigantic web

weaving to displace me.

Sleep, now you come near me softly

like the nursemaid to the child,

and around the sparse flame

you draw a guarding circle.

In his poetic contemplation, Schumann composes a tone poem, which moves the spirit during the transition from day to night and sleep. Schumann sent Hebbel a copy of the score and wrote, “I would have preferred to have enclosed an orchestra with winds blowing and strings bowing, along with a chorus in order to be able to lull the poet into lovely dreams with his own song.”

Robert Schumann: Nachtlied, Op. 108 (South West German Radio Vocal Ensemble; South West German Radio Symphony Orchestra, Baden-Baden; Hans Zender, cond.)

Friedrich Hebbel: Nachtlied

The Swiss composer Walter Courvoisier (1875-1931) initially studied medicine and worked as a doctor. However, in 1902 he abandoned his medical career and went to Munich to study music. He eventually secured a position in the city through an appointment to head the composition class at the Munich Music Academy. Courvoisier’s compositional gift found fruition in the field of vocal music, as he wrote three stage works, several choral pieces and at least 200 songs. His earlier songs are heavily indebted to Hugo Wolf, although Brahms and Schubert are also present. Like his compatriot and fellow composer Othmar Schoeck, Courvoisier adopted Wolf’s technique of providing a brief piano ostinato that could be varied according to the trajectory of the poem. In his setting of Hebbel’s “Nachtlied,” Courvoisier refuses to align himself with “more modernist trends of his time to restrict his powers of expression.”

Walter Courvoisier: Nachtlied, Op. 27 (Ulf Bästlein, baritone; Sascha el Mouissi, piano)

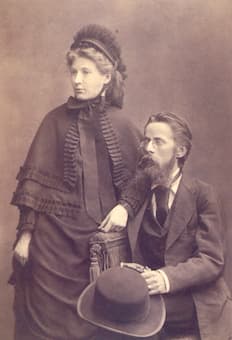

Heinrich and Elisabeth von Herzogenberg

Heinrich von Herzogenberg (1843-1900) studied law at the University of Vienna, and simultaneously composition at the Conservatory under Felix Otto Dessoff. Brahms introduced him to the publisher Rieter-Biederman, “here is a young man,” he writes, “a student of conductor Otto Dessoff, by whom I have seen quite nice songs, and who has the ardent wish to see them printed.” Brahms’ recommendation was the foundation for a lifelong friendship, and it opened a number of professional doors for the 26-year-old composition student. Herzogenberg eventually became professor of composition at the Conservatory in Berlin, and one of the most distinguished composers from the circle of conservative Berlin academics. His compositions bear witness to his great distaste for the music of Richard Wagner, and his piano works, songs and choral works were initially influenced by Schumann, and later, increasingly, by Brahms. Composed around 1890, Herzogenberg’s setting of Hebbel’s “Nachtlied,” for 4 solo voices and piano simultaneously pays respect to Schumann’s sense of declamation and to Brahms’ musical language.

Heinrich von Herzogenberg: 3 Gesänge, Op. 73: No. 1. Nachtlied, “Quellende, schwellende Nacht” (Iris-Anna Deckert, soprano; Ursula Eittinger, alto; Andreas Weller, tenor; Manfred Bittner, bass; Gotz Payer, piano)

Emil Mattiesen

The psychological aspects of Hebbel’s poetry held great fascination for the Baltic-German musician, pedagogue, philosopher and composer Emil Mattiesen (1875-1939). He began his study of music at an early age, but eventually received a PhD from the University of Leipzig with a thesis on John Locke and George Berkeley. Mattiesen travelled extensively in Asia and the Americas, and after completing further studies at the University of Cambridge he published his first book, “An Introduction to the Metapsychology of the Mystical Experience.” He continued to research and publish in the field of parapsychology, and compose Lieder, chamber and organ music. His setting of Hebbel’s “Nachtlied” provides such a mystical experience, as a virtually impassive melody drifts over a solemn succession of chords. An extended piano introduction before the final verse subsequently transports the listener into the otherworldly realm of sleep.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter

Emil Mattiesen: Nachtlied (Ulf Bästlein, baritone; Sascha el Mouissi, piano)