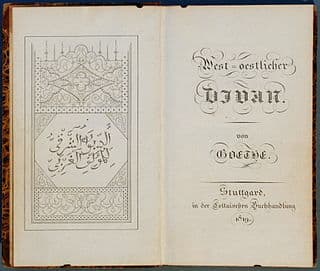

Goethe’s West–östlicher Divan

The Suleika figure we find in Felix Mendelssohn’s settings is far less Oriental and feminine than the one found in his sisters reading. Some scholars have suggested that chromaticism is traditionally linked with Orientalism. “It is supposed to embody cultural Otherness in both French and German cultural spheres, besides its other traditional role in the construction of musical desire.” Yet simultaneously, it served as the musical expression of pain and agony. The unifying factor, it might be argued, is heightened emotionalism and physical excitement. In Felix’s setting, the poetic mood is ushered in by a brief, rising and swelling figure in the piano. It is beautifully evocative of the wind’s motion and the rising temperature of passion.

Felix Mendelssohn: 6 Lieder, Op. 57: No. 3. Suleika, MWV K93 (Mary Bevan, soprano; Malcolm Martineau, piano)

When Johannes Brahms first heard Schubert’s first setting of “Suleika,” he called it the “loveliest song ever written. Schubert was unaware of the poem’s origin, as it had been published under Goethe’s name. Marianne von Willemer wrote the poem on her way to Heidelberg in September 1815 to meet Goethe for a three-day visit, the last time the lovers would ever see each other. Suleika is also traveling to meet her lover Hatem, and carefully listens for tidings carried by the east wind.

Johann Wolfgang von Goethe

What is the meaning of this movement?

Does the East wind bring me happy news?

His wings’ fresh motion

Cools the heart’s deep wounds

Caressing he plays with the dust,

Starts it up in light little clouds,

Drives to the safety of the vine-leaves

the happy little race of insects.

……..

Ah, the true message of the heart,

The breath of Love, life renewed,

Come to me only from his mouth,

Given me only by his breath.

Franz Schubert: Suleika I, Op. 14, No. 1, D. 720 (Tamara Takacs, mezzo-soprano; Jenő Jandó, piano)

Mendelssohn’s visit to Goethe

Contrary to Schubert, Schumann, Mendelssohn and Hensel, Hugo Wolf would have been aware that the “Book of Suleika” represented the intimate correspondence between Goethe and Willemer. Fascinated by this synthesis of symbolism and multivalent meanings, Wolf composed a total of seventeen songs with poems from three of the Divan’s books. Wolf instinctively grasped the strength and quality of his poetic material, and produced settings that allowed him to explore the rich interrelationship and symbolism of the verse. His “Songs of Hatem” were not well received, and Wolf dejectedly wrote, “overall I got the impression that I was not understood, that [critics] were preoccupied with the musical elements alone and forgot about what is new and original in my musical-poetic concept.”

Hugo Wolf: Gesänge des Hatem aus dem Westöstlichen Divan – No. 44. Komm, Liebchen, komm! (Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau, baritone; Daniel Barenboim, piano)

Fartein Valen

Noted for his atonal polyphonic compositions, Fartein Valen (1887-1952) is recognized as one of the great Norwegian composers of the 20th century. His musical language developed a polyphonic style similar to Bach’s counterpoint, but it is based on motivic relationships and dissonances rather than harmonic progressions. Closely aware of the currents of his own time, he was inspired by Arnold Schoenberg to find beauty behind the pretty façade of music and developed his independent expressive atonal musical language. Valen was also interested in philosophy and “his deep religiosity connected to his feelings of affinity with mankind in general, and the spiritual impulses of western civilization.” As such, he felt a strong kinship with painters such as El Greco and Rembrandt, and to authors such as Shakespeare, Shelley and Goethe. And unsurprisingly, we find a “Suleika” setting among his compositions.

Fartein Valen: Gedichte von Goethe, Op. 6 – No. 3. Suleika (Kirsten Landmark Maeland, soprano; Sigmund Hjelset, piano)

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter

Shouldn’t Rimsky-Korsakov be also included in the article, as he also wrote a sublime song named Suleika?