Johann Wolfgang von Goethe

With the possible exception of William Shakespeare, no other poet had such a profound influence on song as Johann Wolfgang von Goethe (1749-1832). For Germany’s greatest poet, music was an essential part of life, and it brought solace and redemption. In his writings, music saves Faust from suicide, music soothes Werther in his bleakest moments, and music restores both Tasso and Wilhelm Meister. The musicality in his verse attracted composers from all around the world, as his poetry was “life affirming and exultant, anguished and introspective, religious or irreverent; whether he was writing wise epigrams or wicked satire, occasional or nonsense verse, or pornography, he was always writing musical poetry that attracted song-composers.” Goethe was able to imitate the great classical writers of Greece and Rome, the Persian lyrics of Hafez and the simplicity of folksong, and he kept renewing himself and reinventing himself right into old age. A good many composers were attracted to “Mignon,” the 13-year old androgynous character in Goethe’s novel Wilhelm Meister. In the novel, she is rescued by the young merchant Wilhelm from a troupe of acrobats, who have kidnapper her from her native Italy and brought her to Germany. The child forms a close bond with Wilhelm, who finds her exotic nature and latent sexuality deeply intriguing. It is only later that we learn that Mignon will die of a broken heart, as she was born out of an incestuous relationship between the harper and his own sister. In “Kennst du das Land” she recalls the scent of Italian citrus trees and expresses her desire to find a father figure in the novel’s young protagonist.

Franz Schubert: Mignon (Kennst du das Land), D. 332 (Marjana Lipovšek, mezzo-soprano; Geoffrey Parsons, piano)

Do you know the land where lemon trees blossom;

where golden oranges glow amid dark leaves?

A gentle wind blows from the blue sky,

the myrtle stands silent, the laurel tall:

do you know it?

There, O there

I desire to go with you, my beloved!

The second verse suggests memories of the marble halls of her home, and the third her traumatic upheaval. Strophic in nature, the verses build from images of Italy and oranges to specific memories of houses and statues. In the final verse it all becomes slightly unhinged, as we learn about mountains and dragons.

Do you know the mountain and its clouded path?

The mule seeks its way through the mist,

in caves the ancient brood of dragons dwells;

the rock falls steeply, and over it the torrent.

Do you know it?

There, O there

lies our way. O father, let us go!

Goethe’s Wilhelm Meister

In general, Goethe really hated to have his poetry set to music, and he wanted the simplest possible accompaniment. In the novel, Goethe describes how Mignon herself performs her song. “She intoned each verse with a certain solemn grandeur, as if she were drawing attention to something unusual and imparting something of importance. When she reached the third line, the melody became more sombre; the words ‘Do you know it?’ were given weightiness and mystery, the ‘There, oh there!’ were suffused with longing, and she modified the phrase ‘I would like to go with you’ each time it was repeated, so that one time it was entreating and urging, the next time pressing and full of promise.”

Ludwig van Beethoven: 6 Songs, Op. 75, No. 1 “Mignon” (Pamela Coburn, soprano; Leonard Hokanson, piano)

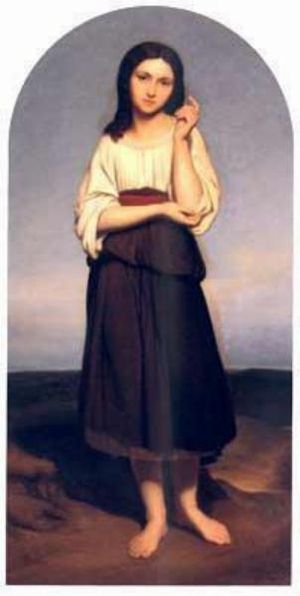

Mignon desires her fatherland,

painting by Ary Scheffer

In April 1816, Franz Schubert mailed Goethe a bundle of manuscripts containing 16 settings of his own poems. It contained masterworks like “Erlkönig,” “Meeresstille,” and “Gretchen am Spinnrade,” but Goethe famously failed to acknowledge the gift and never replied. We are not sure if “Kennest du das Land” was part of the bundle, but Goethe would probably have hated it. While Schubert captures the naiveté and innocence of Mignon in his setting for high soprano, there is no sense of psychological development in the third verse with its Freudian dragons. Although Schubert certainly composed a catchy tune, he probably, as scholars have suggested, never actually read the novel. Beethoven met Goethe only once in 1812, and the two men did not really see eye to eye. Three years earlier, Beethoven had fashioned his setting of “Kennst du das Land,” by including dramatic pauses and focusing on the turbulent forces from Mignon’s past. And while he uses the same melody for all three verses, there is rhythmic animation in the accompaniment when the dragons appear. Goethe, however, absolutely hated it. “Mignon would sing a song, not an aria,” he barked to his friend Václav Tomášek (1774-1850), who composed his own setting in 1815.

Franz Liszt: Mignons Lied (Kennst du das Land) (Chiarastella Onorati, mezzo-soprano; Giulio De Luca, piano)

Illustration from Wilhelm Meister

by Moritz von Schwind

It was Johann Friedrich Reichardt (1752-1814) who composed the first setting of this poem. It is not a simple folk tune, but mirrors the speech pattern of Mignon. And unsurprisingly, Goethe loved it. In due course we find settings by Spohr, Fanny Mendelssohn, Ignaz Moscheles and Gaspare Spontini. After Goethe’s death, Schumann produced a subdued setting, and Franz Liszt composed three settings dating from 1842, 1854, and 1860. Liszt “paints a psychological picture, which none of the earlier composers really did, and he even dared to tamper with the poem.” The psychological uncertainty experienced by Mignon already appears in the second chord, decidedly transporting us into a different realm.

An illustration of a poem by Goethe

© nucius.org

By 1866 Mignon appeared at the Paris Opéra-Comique in an opera by Ambroise Thomas, and Henri Duparc wrote his “Mignon Romance” in 1869, with Tchaikovsky’s Russian setting dating from the same year. Hugo Wolf composed one of the most impressive settings of the poem in 1888. In fact, it is a highly complex aria with massive range and various vocal and accompanimental colors, disclosing that Mignon was older than her years. She stops being an androgynous being and becomes, as Goethe had intended it to be, a psychologically complex girl with great maturity beyond her years. Wolf’s setting makes audible a dimension of what remains unsaid, as “Music and language form a unity not by virtue of the fact that the former repeats what the latter already says anyway, but because music listens to language and makes audible what is latent in it.”

Hugo Wolf: Mignon (Kennst du das Land) (Sophie Karthäuser, soprano; Eugene Asti, piano)

I recently opened an old musical booklet fromTheodor Presser:

German, French and Italian Song Classics (Soprano) from earlier in the 20th century. Editor: Horatio Parker.

Ludwig von Beethoven did spend his lifetime considering the human condition.

I have the Henle Beethoven urtext -Band I & II Klaviersonaten compliments of Verlag.

These days with the Russian Ukrainian conflict I have been looking to my Beethoven pieces:

Appassionata Opus 57 has always struck me as an essay on Nuclear Winter.

Opus 31 Nr. 2 works up the Jewish Wartime Lament – Where is My Mother?

A Greek Orthodox Prayer Chant is interpretted in the Allegretto, Opus 10 Nr. 2.

Beethoven fell out with Napoleon around 1804 and gave us Opus 54 on war and its outcomes.

In my song collection with Presser there is Beethoven’s Mignon for Soprano:

Kennst Du Das Land? Opus 75, Nr. 1

I was amazed at the mention of a Dragon

Bar 75 – Drachen …in hohlen wohnt der Drachen …alte Brut;

es sturst der Feis und uber ihn die Fluth.

Kennst du ihn wohl?

I figure this song needs another look.

V.Putin was born in the Chinese Year of the Dragon

The various meanings of the German text flip one way and then another for interpretation. And I’m not much use at translations in any language. But I do believe that great art reflects culture – in its time and frequently two hundred and more years in the future.

If you could add Beethoven’s little accompaniment to your Mignon listings this would be lovely.