While Johannes Brahms had rightfully hoped of gaining the conductorship of the Hamburg Philharmonic, the post was given to the baritone Julius Stockhausen instead. Dejected and disappointed, Brahms made his first visit to Vienna in the autumn of 1862, staying over the winter. He struck up a number of important acquaintances and friendships and by 1863 he was appointed conductor of the Wiener Singakademie.

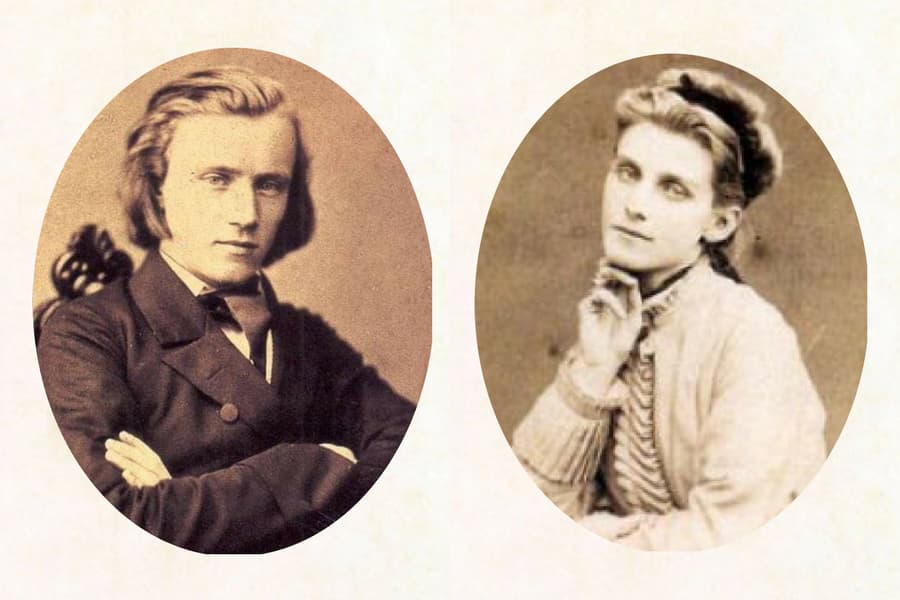

Johannes Brahms in 1865

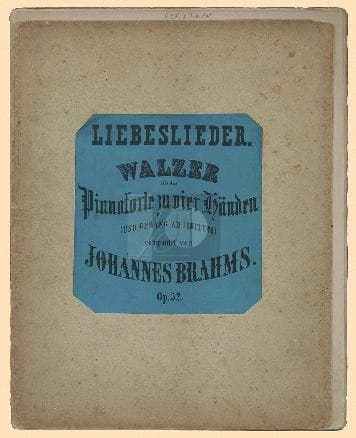

During his move from Hamburg to Vienna, Brahms composed a large body of music in more intimate forms, including lieder, vocal chamber music, and music for piano four-hands. Among these works, we find the Liebeslieder Walzer composed in the common music-making style for domestic parlors. It has been suggested that “these works, in a deliberately popular style, were overwhelmingly responsible for spreading Brahms’ reputation to the general music-buying public, and became the chief source of his personal wealth.”

Tell me, my sweetest girl,

who with your glances

have kindled in my cool breast

these wild, passionate feelings!

Will you not relent, will you,

with an excess of virtue,

live without love’s rapture,

or do you wish me to come to you?

To live without love’s rapture,

is a bitter fate I would not suffer.

Come, then, with your dark eyes,

come, when the stars beckon!

(All English translations © by Richard Stokes)

Johannes Brahms: Lieberslieder Waltzes, Op. 52, No 1 “Speak, maiden” (Matthew Polenzani, tenor; Magdalena Kožená, mezzo-soprano; Thomas Quasthoff, bass; Andrea Rost, soprano; Yefim Bronfman, piano; James Levine, piano)

Brahms’ Liebeslieder Waltzes

In a letter to the publisher, Brahms dismissed his set of 18 Liebeslieder Walzer as “trifles,” but he was clearly aware of their possible appeal. As he writes, “I will gladly risk being called an ass if they don’t give a few people pleasure.” In the event, they became hugely popular and Brahms subsequently produced a four-hand piano arrangement and an orchestral suite. The original score calls for “piano four hands and voice ad libitum,” and appears a likely invitation to amateurs to present these waltz-songs in a variety of different forms and groupings.

The wildly lashed waves

dash against the rocks;

whoever has not learned to sigh

will learn it when he loves.

Johannes Brahms: Lieberslieder Waltzes, Op. 52, No 2 “The flood rushes against the rocks” (Matthew Polenzani, tenor; Magdalena Kožená, mezzo-soprano; Thomas Quasthoff, bass; Andrea Rost, soprano; Yefim Bronfman, piano; James Levine, piano)

Julie Schumann at 20 years old

We don’t know exactly what prompted Brahms to compose his initial Liebeslieder set, but one emotional stimulus might well have been his infatuation with Julie Schumann, the third daughter of Clara and Robert Schumann. She was “a sweet but sickly child, and considered the prettiest of the Schumann daughters. Brahms never communicated his youthful infatuation and it must have been quite a shock when it was announced that she would marry the Italian count Vittorio Amadeo Radicati di Marmorito. Brahms was devastated but still acted as her best man at her wedding. On the evening of her marriage, Brahms showed Clara his Alto Rhapsody and declared that this was his song for Julie’s engagement. “The text, with its metaphysical portrayal of a misanthropic soul who is urged to find spiritual sustenance and throw off the shackles of his suffering, has powerful parallels in Brahms’s life and character.” Clara finally understood, and she was predictably shocked.

O women, o women,

how they delight the heart!

I should have long since turned monk,

were it not for women!

Johannes Brahms: Lieberslieder Waltzes, Op. 52, No 3 “Oh, these women” (Matthew Polenzani, tenor; Thomas Quasthoff, bass; Yefim Bronfman, piano; James Levine, piano)

Brahms and Julie Schumann

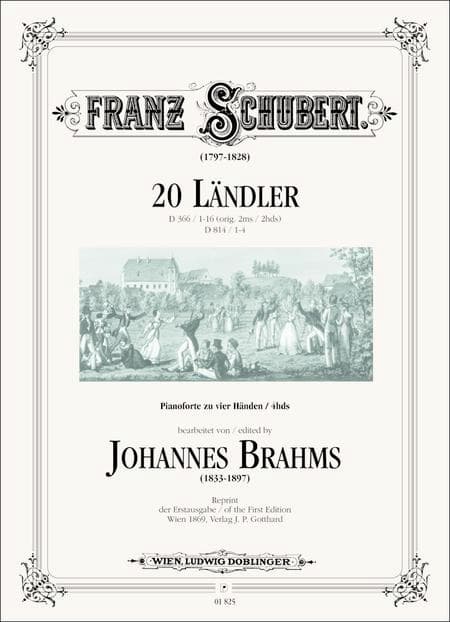

His infatuation with Julie Schumann aside, Brahms also looked towards one of his musical heroes, Franz Schubert. From his earliest days in Vienna, Brahms played a leading role in contemporary efforts to preserve the memory and music of Schubert. Brahms was a passionate collector of the composer’s autographs, copied manuscripts he could not obtain for himself, and even saw a number of pieces into print. “Of the several first editions for which Brahms could claim responsibility, perhaps the most striking—both based on autographs in his own rich library—are the 12 Ländler, D 790 (1864), and the 20 Ländler, D 366 and D 814 (1869). Notably, both sets of dances inspired an immediate artistic response: at about the same time when each was published, Brahms composed a cycle of dances of his own, the Waltzes for Piano Duet, op. 39 (1865), and the Liebeslieder Waltzes, op. 52 (1869).”

Like a lovely sunset

I, a humble girl, would glow,

and find favour with one alone,

radiating endless rapture.

Johannes Brahms: Lieberslieder Waltzes, Op. 52, No 4 “Like evening’s beautiful glow” (Magdalena Kožená, mezzo-soprano; Andrea Rost, soprano; Yefim Bronfman, piano; James Levine, piano)

Brahms’ edition of Schubert’s Ländler

A Brahms scholar has asserted the significance of this interaction between editorial and compositional endeavors. “Brahms’ two editions of Schubert Ländler were influenced very much by the same artistic sensibilities, in this case, a desire for tonal and motivic coherence among numbers, that shaped his own cycles of waltzes. That is, Brahms’ editorial decisions reflect his personal compositional stance and aesthetic.” It seems that Brahms the musicologist profoundly influenced Brahms the composer.

The green tendrils of the vine

creep low along the ground.

How gloomy, too,

the lovely young girl looks!

Why, green tendrils!

Why do you not stretch up to the sky?

Why, lovely girl!

Why is your heart so heavy?

How can the vine grow tall

without support?

How can the girl be joyful,

when her lover’s far away?

Johannes Brahms: Lieberslieder Waltzes, Op. 52, No 5 “The green vine” (Matthew Polenzani, tenor; Magdalena Kožená, mezzo-soprano; Thomas Quasthoff, bass; Andrea Rost, soprano; Yefim Bronfman, piano; James Levine, piano)

Initially, Brahms was looking to have his waltzes performed in informal musical evening settings, “similar to those intended for Schubert’s dances.” Interestingly, Brahms specifically requested that each of his movements was to be copied onto a separate sheet of paper, probably not entirely sure how to order such seemingly unrelated pieces. As has been pointed out, “Brahms faced a similar struggle in the ordering for the Schubert dances.”

A pretty little bird flew off

into a garden full of fruit.

Were I a pretty little bird,

I’d not hesitate, I’d do the same.

But treacherous lime-twigs lay in wait;

the poor bird could not fly away.

Were I a pretty little bird,

I’d hesitate, not do the same.

The bird alighted on a fair hand,

the lucky thing wanted nothing more.

Were I pretty little bird,

I’d not hesitate, I’d do the same.

Johannes Brahms: Lieberslieder Waltzes, Op. 52, No 6 “The little, pretty bird” (Matthew Polenzani, tenor; Magdalena Kožená, mezzo-soprano; Thomas Quasthoff, bass; Andrea Rost, soprano; Yefim Bronfman, piano; James Levine, piano)

Brahms’ experience with the editorial process necessitated making decisions to place pieces that “Schubert never intended to perform together” into a coherent order. However, as Brahms shifts from editor of the Twenty Ländler to composer of the Liebeslieder Walzer Op. 52, he replicates his editorial behavior by composing eighteen movements that seemed to function autonomously. “Brahms ordered them into a whole piece that is a sum of what were, initially, unrelated parts.” The external influence and experience that Brahms had gained from editing the Twenty Ländler “not only shaped the Liebeslieder Walzer from a compositional perspective, but also added a sense of depth, significance, and credibility to Brahms’ repertoire.”

All seemed rosy

at one time

with my life,

with my love!

Through a wall,

through ten walls,

my lover’s gaze

would reach me.

But now, alas,

I stand in front

of his cool gaze,

neither his eyes,

nor his heart,

takes note of me.

Johannes Brahms: Lieberslieder Waltzes, Op. 52, No 7 “Formerly it was well-ordered” (Andrea Rost, soprano; Yefim Bronfman, piano; James Levine, piano)

Brahms tinkered with the order of his eighteen love-songs, and even with their keys until they went to press. He even considered releasing them in two or even three books before settling on just one. “Delivered in one passionate outpouring without a break, they cohere wonderfully.” Sometimes the same emotional thread runs through two or three consecutive songs, other times there’s an abrupt change of register, but working on a tiny canvas, with many songs lasting barely a minute, Brahms finds a perfect form and colouring for each one.”

When you gaze at me so tenderly

and so full of love –

all the gloom that assails me

fades away.

Oh, do not let this love’s

sweet ardour vanish!

No one will love you

as truly as I.

Johannes Brahms: Lieberslieder Waltzes, Op. 52, No 8 “If your eye is mild” (Matthew Polenzani, tenor; Magdalena Kožená, mezzo-soprano; Thomas Quasthoff, bass; Andrea Rost, soprano; Yefim Bronfman, piano; James Levine, piano)

Commentators have pointed to an additional influence in the form of Waltz King Johann Strauss. The ninth song “Am Donaustrande” (On the banks of the Danube) provides clear echoes of the Blue Danube Waltz. And we know that Brahms later in life gave a young admirer his autograph accompanied by the opening bars of the waltz, to which he appended the words “Leider nicht von Brahms” (Alas not by Brahms.)

On the Danube’s shore there stands a house,

from its windows a rosy girl looks out.

The girl is excellently guarded,

ten bolts are fixed to her door.

Ten bolts of iron – a mere trifle!

I’ll break them down,

as though they were glass.

Johannes Brahms: Lieberslieder Waltzes, Op. 52, No 9 “On the Danube shore” (Matthew Polenzani, tenor; Magdalena Kožená, mezzo-soprano; Thomas Quasthoff, bass; Andrea Rost, soprano; Yefim Bronfman, piano; James Levine, piano)

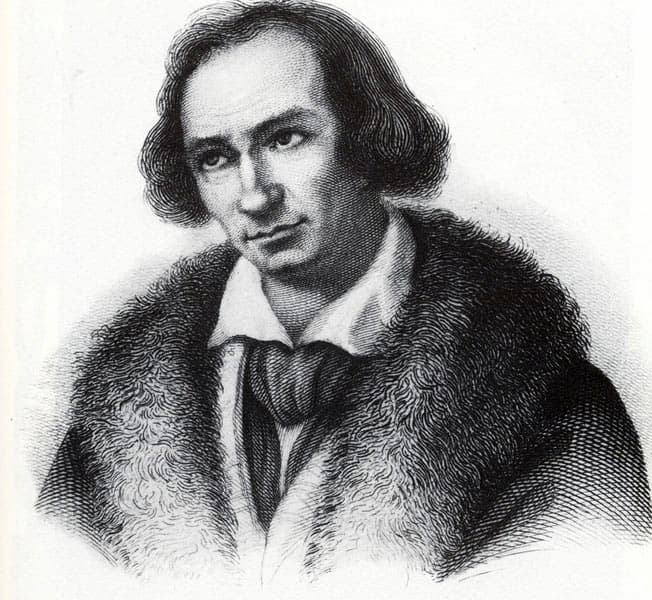

Georg Friedrich Daumer

Clara Schumann wrote in her diary on 16 July 1869. “At the beginning of this month, Johannes brought me some charming waltzes for 4 hands and 4 voices, sometimes two and two, sometimes all four together, with very pretty words, chiefly of the folk-song type. They are extraordinarily attractive, charming even without the voices, and I very much enjoy playing them.” After hearing a reading of the waltzes with voices on 24 August, she wrote, “They are delightfully dainty and charming, of really remarkable musical form and melody.”

Ah, how gently the stream

meanders through the meadow!

Ah, how sweet, when love

finds itself requited!

Johannes Brahms: Lieberslieder Waltzes, Op. 52, No 10 “Oh how gentle the spring” (Matthew Polenzani, tenor; Magdalena Kožená, mezzo-soprano; Thomas Quasthoff, bass; Andrea Rost, soprano; Yefim Bronfman, piano; James Levine, piano)

While the Liebeslieder Waltzes became an instant success, the poet whose poems and translations Brahms set in the cycle, is largely unknown. Georg Friedrich Daumer (1800-1875) was seen as an important philosopher and poet. While his philosophical works exerted influence on Ludwig Feuerbach and Karl Marx, his “free translations and original works in the guise of the fourteenth-century Persian poet Hafiz, first published in 1846, were wildly popular.”

No, it is not possible

to put up with these people;

they interpret everything

so spitefully.

If I’m happy, they say

I harbour lewd desires;

if I’m quiet, they say

I’m madly in love.

Johannes Brahms: Lieberslieder Waltzes, Op. 52, No 11 “No, one can’t get along” (Matthew Polenzani, tenor; Magdalena Kožená, mezzo-soprano; Thomas Quasthoff, bass; Andrea Rost, soprano; Yefim Bronfman, piano; James Levine, piano)

Daumer’s philosophical views and strategies for religious reform are laid out in dozens of books, and the majority of his poetry collections include prefaces or epilogues that explain his rationale for each. His best-known collection Hafis, published in two volumes in 1846 and 1852, respectively, “is actually a group of very free translations and imitations of songs by the fourteenth-century Persian poet Hafiz, whose rhyming couplets, many of which concern love, wine, and nature, are traditionally interpreted allegorically by Sufic Muslims.” The Catholic Encyclopedia describe Daumer as “an enemy of Christianity,” but it has been suggested that “Brahms, an agnostic, was drawn to Daumer’s anticlericalism, as well as to the mystical, lyrical, sensual quality of his poetry.”

Locksmith, come, make me padlocks,

padlocks without number!

So that once and for all I can shut

their malicious mouths.

Johannes Brahms: Lieberslieder Waltzes, Op. 52, No 12 “Locksmith get up and make padlocks” (Matthew Polenzani, tenor; Magdalena Kožená, mezzo-soprano; Thomas Quasthoff, bass; Andrea Rost, soprano; Yefim Bronfman, piano; James Levine, piano)

Late in Daumer’s life, Brahms, who had never met the poet, or even corresponded with him, decided to pay him a visit. As he later wrote to his friend, poet Klaus Groth, “in a quiet room I met my poet. Ah, he was a little dried-up old man!.. I soon perceived that he knew nothing either of me or of my compositions, or anything at all of music. And when I pointed to his ardent, passionate verses, he gestured, with a tender wave of his hand, to a little old mother almost more withered than himself, saying, ‘Ah, I have only loved the one, my wife!”

A little bird flies through the skies,

searching for a branch;

thus does one heart seek another,

where it might rest in bliss.

Johannes Brahms: Lieberslieder Waltzes, Op. 52, No 13 “Little bird rushes through the air” (Magdalena Kožená, mezzo-soprano; Andrea Rost, soprano; Yefim Bronfman, piano; James Levine, piano)

Georg Friedrich Daumer’s Hafis

In the event, Daumer was Brahms’ favorite poet as he set about twenty of Daumer’s poems in addition to thirty-two contained in his two sets of Liebeslieder Waltzes. Here, Brahms references a Daumer collection, also published in two volumes, of translations and imitations of folk poetry, based on Russian, Polish, Hungarian, Turkish, Latvian, and Sicilian sources. Titled Polydora: Ein Weltpoetisches Liederbuch, Daumer freely used source material, so that “it is difficult to differentiate between his original work and any authentic folk poetry that he may have used.” Both volumes concern themselves with the many facets of love, including longing, reluctance, denial, sadness, obsession, joy, and rapture.

See how clear the waves are,

when the moon shines down!

You, my dearest love,

love me in return.

Johannes Brahms: Lieberslieder Waltzes, Op. 52, No 14 “Look how clear the wave” (Matthew Polenzani, tenor; Thomas Quasthoff, bass; Yefim Bronfman, piano; James Levine, piano)

Once he had made his poetic selection, Brahms composed the music rather quickly. In his music, Brahms makes specific musical comments on the meaning of each poem. Selected poems have longer, more serious texts, and others read like pithy proverbs. “Mirroring true love, the emotions put forth are quite varied, some touching, some funny, and some remorseful.” Scholars have suggested that “with a little imagination, it is possible to construct a connected narrative, such as one finds in the typical Romantic song cycle,” even though there is no evidence that Brahms had any such thing in mind.

The nightingale sings so sweetly,

when the stars are sparkling –

Love me, dear heart,

kiss me in the dark!

Johannes Brahms: Lieberslieder Waltzes, Op. 52, No 15 “Nightingale, you sing so beautifully” (Matthew Polenzani, tenor; Magdalena Kožená, mezzo-soprano; Thomas Quasthoff, bass; Andrea Rost, soprano; Yefim Bronfman, piano; James Levine, piano)

Despite their popular appeal, their brevity, their characteristic beats, and their typical pattern of 4-line texts in which each couplet is sung and then repeated, these pieces are highly sophisticated. They are individual miniatures that are “jolly and light-hearted, ironic, introspective, or sad. In a number of songs, the sentiment is incomplete or unexplained, as the musical writing exhibits both elegant sophistication and clever world painting.”

Love is a dark pit,

an all too dangerous well;

I tumbled in, alas,

can neither hear nor see,

can only recall my rapture,

and only bemoan my grief.

Johannes Brahms: Lieberslieder Waltzes, Op. 52, No 16 “Love is a dark shaft” (Matthew Polenzani, tenor; Magdalena Kožená, mezzo-soprano; Thomas Quasthoff, bass; Andrea Rost, soprano; Yefim Bronfman, piano; James Levine, piano)

The craftsmanship of these miniatures is highly ingenious, with the harmonic shifts subtly negotiated, and the instrumental accompaniment acting as an equal partner while the alternation of male and female voices maintaining a fine balance. Brahms’ musical language demonstrates extraordinary technique and craft. His expressive use of melody, imaginative use of harmony, and his deep understanding of counterpoint permeate the entire collection.

Do not wander, my love, out there

in the fields!

The ground would be too wet

for your tender feet.

The paths and tracks

are all flooded out there,

so abundantly have my eyes

been weeping.

Johannes Brahms: Lieberslieder Waltzes, Op. 52, No 17 “My light, don’t go away” (Matthew Polenzani, tenor; Yefim Bronfman, piano; James Levine, piano)

However, probably most impressive is the way Brahms controls the rhythmic and metric flow of these miniatures. In his study of early music Brahms paid particular attention to melodies that “do not conform with either original or editorial bar lines.” When Brahms came upon unbarred folk melodies “he carefully pondered what meter or meters the text demanded…experimenting with barrings that yield various solutions in regular and mixed meters.” In his Liebeslieder Waltzes and elsewhere, “Brahms uses the tools of musical motion to create a composition that goes beyond simple melody and harmonic understanding.” In fact, metric conflict becomes a well-established element of his compositional craft.

The foliage trembles,

where a bird in flight

has brushed against it.

And so my soul

trembles too, shuddering

with love, desire and pain,

whenever it thinks of you.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up for our E-Newsletter

Johannes Brahms: Lieberslieder Waltzes, Op. 52, No 18 “Bushes are trembling” (Matthew Polenzani, tenor; Magdalena Kožená, mezzo-soprano; Thomas Quasthoff, bass; Andrea Rost, soprano; Yefim Bronfman, piano; James Levine, piano)