In the woods in May 1819, a nightingale sings of summer and her notes fall on the ears of the poet John Keats. He uses the metaphor of the audible but invisible bird, singing to the open skies, as a metaphor for the final mortality of all. The poem opens with the poet feeling numb, as though drugged.

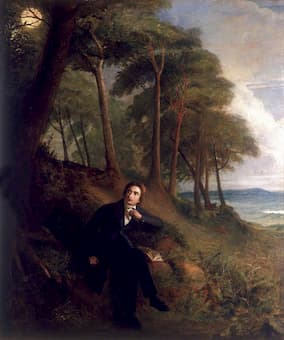

Joseph Severn’s depiction of Keats

listening to the nightingale (c. 1845)

My heart aches, and a drowsy numbness pains

My sense, as though of hemlock I had drunk,

Or emptied some dull opiate

and closes with the nightingale flying away and the poet questioning what he may or may not have heard.

Adieu! adieu! thy plaintive anthem fades

Past the near meadows, over the still stream,

Up the hill-side; and now ’tis buried deep

In the next valley-glades:

Was it a vision, or a waking dream?

Fled is that music:—Do I wake or sleep?

According to a friend, Keats wrote the poem in a single day, in about two to three hours, on Hampstead Heath, either behind the Spaniards Inn or at his house close by. In the poem, Keats rejects the pursuit of pleasure he had advocated in earlier poems and explores idea of nature, transience, and, ultimately mortality. The poem is long, 80 lines in 8 stanzas, but remains one of the most popular poems of Keats’ small output. (The full poem is at the bottom of this article).

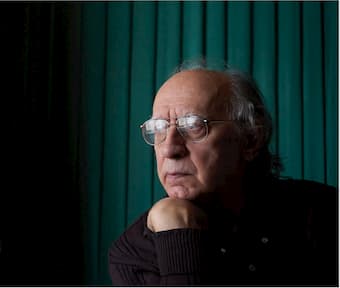

Hamilton Harty

Keats died of tuberculosis at age 25, having published just over 50 poems, but the Ode to the Nightingale and its preoccupation with his own death and the nightingale’s immortality through its song poses an essential Romantic quandary.

Over the space of a century, four different composers took up the poem, each finding something unique in its lines.

In 1901, composer Hamilton Harty moved to London and made his way as an accompanist. One of the singers he met was Agnes Nicholls, considered one of the leading young sopranos of her day. They married in 1904 and in 1907, wrote Ode to the Nightingale. Agnes was its dedicatee and the soloist at its premiere at the Cardiff Festival in 1907. The singer’s soaring vocal phrases are matched by the rich orchestral writing.

Hamilton Harty: Ode to a Nightingale (Heather Harper, soprano; Ulster Orchestra; Bryden Thomson, cond.)

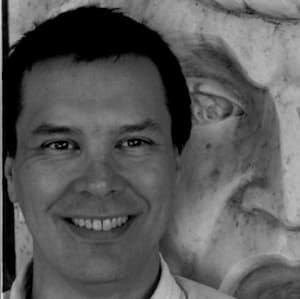

Valentin Silvestrov

Lithuanian composer Valentin Silvestrov set the poem in 1985 in Russian (translation by Yevgenij Vitkovskij). It is seen as ‘a musical reflection of Keats’s evocation of that water that we are unable to hold in our hands for more than a few seconds—our life.’ Supporting the song are a unique ensemble of piano, harp, vibraphone and wind instruments that evoke the unique song of the bird.

Valentin Silvestrov: Ode to a Nightingale (Inna Galatenko, soprano; Oleg Bezborodko, piano; Lithuanian National Symphony Orchestra; Christopher Lyndon-Gee, cond.)

Geoffrey Gordon

In 2015, American composer Geoffrey Gordon took up the call of Keats in a work for chorus and cello. He says, ‘the work vocalises a rapt, suspended state between the reality of death and Arcadian bliss…’. His opening uses dissonances to convey Keats’ languid state at the beginning of the poem. The cello offers an interesting counterbalance to the fluidity of the voices, sometimes echoing them in its entrances and then spinning away.

Geoffrey Gordon: Ode to a Nightingale: My heart aches… – (Toke Møldrup, cello; Mogens Dahl Chamber Choir; Mogens Dahl, cond.)

By the end, the emotions are higher as he brings himself back from the world of the nightingale to his own questions about his state: awake or sleep.

Geoffrey Gordon: Ode to a Nightingale: Forlorn… (Toke Møldrup, cello; Mogens Dahl Chamber Choir; Mogens Dahl, cond.)

Will Todd

The English composer Will Todd uses Keats’ romantic imagery and emotion to delve into the death, fantasy, love, hope and despair of the poem. He opens with a recording of the nightingale itself, singing its sweet song in the summer.

By verse 8, Todd has built to an incredible height of emotion, underscored by the timpani beats. It closes with the question “Do I wake or sleep?” in an almost dreamlike manner and the nightingale returns.

Will Todd: Choral Symphony No. 4, “Ode to a Nightingale”: Start (Hertfordshire Chorus; BBC Concert Orchestra; David Temple, cond.)

Will Todd: Choral Symphony No. 4, “Ode to a Nightingale”: Verse 8 (Hertfordshire Chorus; BBC Concert Orchestra; David Temple, cond.)

These highly imaginative settings of one of the most important of the Romantic poems by one of the most important, if short-lived Romantic poets leaves us room to think further about these questions of life, death and immortality.

Ode to a Nightingale

By John Keats

My heart aches, and a drowsy numbness pains

My sense, as though of hemlock I had drunk,

Or emptied some dull opiate to the drains

One minute past, and Lethe-wards had sunk:

‘Tis not through envy of thy happy lot,

But being too happy in thine happiness,—

That thou, light-winged Dryad of the trees

In some melodious plot

Of beechen green, and shadows numberless,

Singest of summer in full-throated ease.

O, for a draught of vintage! that hath been

Cool’d a long age in the deep-delved earth,

Tasting of Flora and the country green,

Dance, and Provençal song, and sunburnt mirth!

O for a beaker full of the warm South,

Full of the true, the blushful Hippocrene,

With beaded bubbles winking at the brim,

And purple-stained mouth;

That I might drink, and leave the world unseen,

And with thee fade away into the forest dim:

Fade far away, dissolve, and quite forget

What thou among the leaves hast never known,

The weariness, the fever, and the fret

Here, where men sit and hear each other groan;

Where palsy shakes a few, sad, last gray hairs,

Where youth grows pale, and spectre-thin, and dies;

Where but to think is to be full of sorrow

And leaden-eyed despairs,

Where Beauty cannot keep her lustrous eyes,

Or new Love pine at them beyond to-morrow.

Away! away! for I will fly to thee,

Not charioted by Bacchus and his pards,

But on the viewless wings of Poesy,

Though the dull brain perplexes and retards:

Already with thee! tender is the night,

And haply the Queen-Moon is on her throne,

Cluster’d around by all her starry Fays;

But here there is no light,

Save what from heaven is with the breezes blown

Through verdurous glooms and winding mossy ways.

I cannot see what flowers are at my feet,

Nor what soft incense hangs upon the boughs,

But, in embalmed darkness, guess each sweet

Wherewith the seasonable month endows

The grass, the thicket, and the fruit-tree wild;

White hawthorn, and the pastoral eglantine;

Fast fading violets cover’d up in leaves;

And mid-May’s eldest child,

The coming musk-rose, full of dewy wine,

The murmurous haunt of flies on summer eves.

Darkling I listen; and, for many a time

I have been half in love with easeful Death,

Call’d him soft names in many a mused rhyme,

To take into the air my quiet breath;

Now more than ever seems it rich to die,

To cease upon the midnight with no pain,

While thou art pouring forth thy soul abroad

In such an ecstasy!

Still wouldst thou sing, and I have ears in vain—

To thy high requiem become a sod.

Thou wast not born for death, immortal Bird!

No hungry generations tread thee down;

The voice I hear this passing night was heard

In ancient days by emperor and clown:

Perhaps the self-same song that found a path

Through the sad heart of Ruth, when, sick for home,

She stood in tears amid the alien corn;

The same that oft-times hath

Charm’d magic casements, opening on the foam

Of perilous seas, in faery lands forlorn.

Forlorn! the very word is like a bell

To toll me back from thee to my sole self!

Adieu! the fancy cannot cheat so well

As she is fam’d to do, deceiving elf.

Adieu! adieu! thy plaintive anthem fades

Past the near meadows, over the still stream,

Up the hill-side; and now ’tis buried deep

In the next valley-glades:

Was it a vision, or a waking dream?

Fled is that music:—Do I wake or sleep?

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter