Joseph von Eichendorff

Joseph von Eichendorff was the quintessential poet of the German landscape. His indirect mode of representation is almost pictorial. Fields, trees, woods, river and streams conjure up images experienced at morning, noon, evening, dusk, and night. Each moment has its particular mood, from the delight in rebirth at dawn to the gentle awe of summer twilight. The imagery suggest a higher, spiritual meaning, with life on earth, full of temptations, confusion, and suffering, appears as a journey or pilgrimage toward a divine home.

Moonrise over the Sea by Caspar David Friedrich

Eichendorff associates the themes of ineffability—themes or ideas that are incapable of being expressed or described in words—and of transcendence with the image of the night. It’s not significant what the night might actually have to say, but the sense that it is communicating becomes the major focus. This sense of communication leads to the feeling of epiphany and oneness with nature.

In one of his final compositions, and during intense mourning for his sister’s death, Felix Mendelssohn composed music to Eichendorff’s “Nachtlied.” The first stanza, with its reference to the passage of day, the night that takes the unsuspecting many with it, and the distantly tolling bells, determines the general affect of the song.

Felix Mendelssohn: 6 Lieder, Op. 71: No. 6. Nachtlied (Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau, baritone; Wolfgang Sawallisch, piano/cond.)

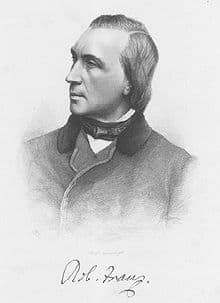

Robert Franz

During his career, Robert Franz (1815-1892) published about two hundred eighty songs for voice and piano. Franz was the Lied composer par excellence, a specialist who wrote almost exclusively songs. Franz was a highly private individual, and his conception of art was revealed in the small and intimate, far removed from the hustle and bustle of the concert stage. He abhorred self-indulgent and sensual music, “crassly materialistic,” is how he frequently characterized the musical approaches of most of his contemporaries, including those of Brahms, Bruch, and Wagner.

The Evening by by Caspar David Friedrich

Franz espoused an art that maintained equilibrium, simplicity, beauty, and an almost puritanical quality. “My songs,” he writes, “should not excite the nerves but to help people find peace and tranquility.” A good many of the set texts are by Heinrich Heine, but Eichendorff is predictably represented by twelve settings as well. The majority of his Eichendorff settings turn their expressive ardor inward, and they exhibit warm, gently passionate sentiments, often tinged with feelings of nostalgia and melancholy, as we can clearly hear in his setting of “Gute Nacht” (Good Night).

Die Höh’n und Wälder schon steigen | The heights and forests already climb |

Immer tiefer in’s Abendgold; | Ever deeper into the evening sunset; |

Ein Vöglein frägt in den Zweigen | A little bird asks in the branches |

Ob es Liebchen grüssen sollt’? | Whether it should greet its sweetheart? |

|

|

O Vöglein, du hast dich betrogen, | Oh little bird, you have deceived yourself, |

Sie wohnet nicht mehr im Tal, | She lives no more in the valley, |

Schwing’ auf dich zum Himmelsbogen, | Soar upon heaven’s vault, |

Grüss’ sie droben zum letztenmal. | Greet her up there for the last time. |

Robert Franz: 12 Gesänge, Op. 5: No. 7. Gute Nacht (Mitsuko Shirai, mezzo-soprano; Hartmut Höll, piano)

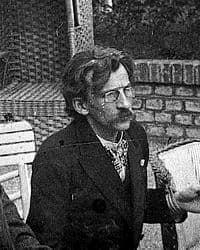

Hans Pfitzner, 1905

For Hans Pfitzner (1869-1949), who described himself as an “anti-modernist,” the path to setting Lieder originated not with the poetry but with musical inspiration. Pfitzner composed roughly 150 songs, during his career, and that includes 19 Eichendorff poems set between 1888 and 1931. Pfitzner’s Eichendorff settings share an innate poetic intensity, “their encapsulation in one-or two-line key phrases of the poems’ entire essence.” Pfitzner elevated literal declamation to a melodic principle, and making vocal melody subservient to the spoken word set to music. As he once wrote, “Nobody can be so perverse as to speak of the works of a great composer without regarding his musical conception as the starting-point, the guiding principle.” A good many of Pfitzner’s settings, including Eichendorff’s “In the Night,” might be considered among the finest songs from the early 20th century.

Ich stehe in Waldesschatten | I stand in forest-shadows |

Wie an des Lebens Rand, | as on the verge of life, |

Die Länder wie dämmernde Matten, | the lands like dusky meadows, |

Der Strom wie ein silbern Band. | the stream like a silver ribbon. |

|

|

Von fern nur schlagen die Glocken | Far away bells are ringing |

Über die Wälder herein. | into the woods. |

Ein Reh hebt den Kopf erschrocken | Alerted, a deer raises its head, |

Und schlummert gleich wieder ein. | and is soon sleeping again. |

|

|

Der Wald aber rühret die Wipfel | But the trees move their tops, |

Im Traum von der Felsenwand. | dreaming of walls of rock. |

Denn der Herr geht über die Gipfel | For god walks over the heights, |

Und segnet das stille Land. | blessing the silent land. |

Hans Pfitzner: 5 Lieder, Op. 26: No. 2. Nachts (Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau, baritone; Wolfgang Sawallisch, piano/cond.)

Northern Sea in the Moonlight by Caspar David Friedrich

The penultimate song in Schumann’s Liederkreis, Op. 39 returns us to the forest. The narrator, now hyper-alert to every passing sound and stimulus is left empty by the coming of night. Schumann’s highly erratic and unsettling setting flows into the final song, “Frühlingsnacht.” This almost seems like a conventional conclusion after these forest hallucinations as the rustling of the spring evening once again speaking of love and happiness. But Eichendorff and Schumann remain ambiguous until the end, as the unbridled joy might only be an illusion. Yet, as we know today, Robert did finally get his Clara, and the evanescent wisps of countermelody and triumphant final “she is yours,” are shimmering visions of physical and spiritual elation.

Robert Schumann: Liederkreis, Op. 39 – No. 12. Fruhlingsnacht (Thomas E. Bauer, baritone; Uta Hielscher, piano)