Roald Dahl, born on 13 September 1916 in Cardiff, has been called “one of the greatest storytellers for children of the 20th century.” From Sophie’s adventures in the BFG and James’ journey into the Giant Peach, to Matilda’s bravery and Charlie’s first step into the world of Willie Wonka, Dahl’s stories have always celebrated the incredible potential of young people and the power of kindness. Dahl ranks amongst the world’s best-selling fiction authors, and his short stories and poems are known for their often unexpected macabre and dark endings. And predictably, a good many of his stories and poems have been set to music.

Martin Butler: Dirty Beasts, “The Pig” (Simon Callow, reader; New London Chamber Ensemble; Martin Butler, piano)

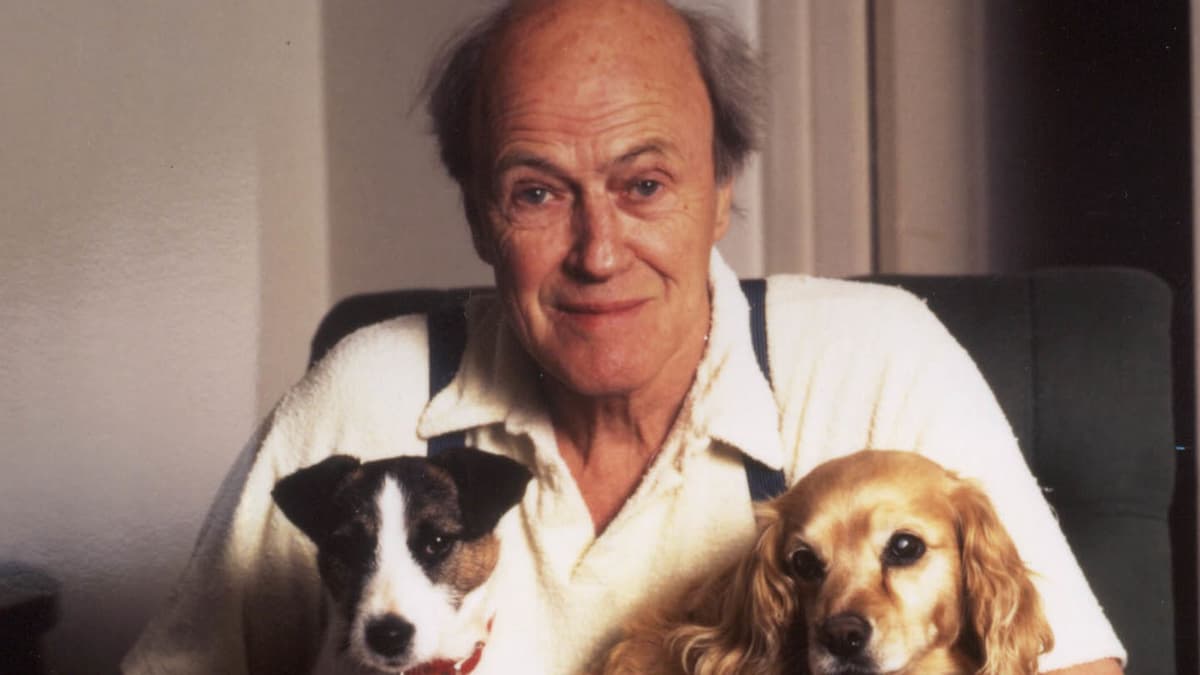

Roald Dahl

In England once there lived a big

And wonderfully clever pig.

To everybody it was plain

That Piggy had a massive brain.

He worked out sums inside his head,

There was no book he hadn’t read.

He knew what made an airplane fly,

He knew how engines worked and why.

He knew all this, but in the end

One question drove him round the bend:

He simply couldn’t puzzle out

What LIFE was really all about.

What was the reason for his birth?

Why was he placed upon this earth?

His giant brain went round and round.

Alas, no answer could be found.

Till suddenly one wondrous night.

All in a flash he saw the light.

He jumped up like a ballet dancer

And yelled, “By gum, I’ve got the answer!”

“They want my bacon slice by slice

To sell at a tremendous price!

They want my tender juicy chops

To put in all the butchers’ shops!

They want my pork to make a roast

And that’s the part’ll cost the most!

They want my sausages in strings!

They even want my chitterlings!

The butcher’s shop! The carving knife!

That is the reason for my life!”

Such thoughts as these are not designed

To give a pig great piece of mind.

Next morning, in comes Farmer Bland,

A pail of pigswill in his hand,

And piggy with a mighty roar,

Bashes the farmer to the floor …

Now comes the rather grisly bit

So let’s not make too much of it,

Except that you must understand

That Piggy did eat Farmer Bland,

He ate him up from head to toe,

Chewing the pieces nice and slow.

It took an hour to reach the feet,

Because there was so much to eat,

And when he finished, Pig, of course,

Felt absolutely no remorse.

Slowly he scratched his brainy head

And with a little smile he said,

“I had a fairly powerful hunch

That he might have me for his lunch.

And so, because I feared the worst,

I thought I’d better eat him first.”

Roald Dahl Collection

Paul Patterson: The Three Little Pigs, Op. 92c “The animal I really dig” (Rebecca Kenny, narrator; Magnard Ensemble)

Born to Norwegian immigrants in Llandaff, Wales on 13 September 1916, he often visited his grandparents in Oslo, Norway. He heard marvelous stories about witches and trolls, swam in the ice-blue fjords, and ate ice cream with “thousands of little chips of crisp burnt toffee mixed into it.”

Paul Patterson: The Three Little Pigs, Op. 92c “A Pig who is a fool” (Rebecca Kenny, narrator; Magnard Ensemble)

Apparently, he was a rather mischievous child, full of energy “and very good in finding trouble.” His father was a successful ship broker, and his formidable mother Sofie looked after the five children.

Paul Patterson: The Three Little Pigs, Op. 92c “First Pig” (Rebecca Kenny, narrator; Magnard Ensemble)

Dahl described his boarding school years as “days of horrors, filled with rules, rules and still more rules that had to be obeyed.” Caning was still a favourite educational tool of the day, and Dahl reports, “There is no small boy in the world who wouldn’t be afraid of it. It wasn’t simply an instrument for beating you. It was a weapon for wounding. It lacerated the skin. It caused severe black and scarlet bruising that took three weeks to disappear, and all the time during those three weeks, you could feel your heart beating along the wounds.”

Paul Patterson: The Three Little Pigs, Op. 92c “Wolf” (Rebecca Kenny, narrator; Magnard Ensemble)

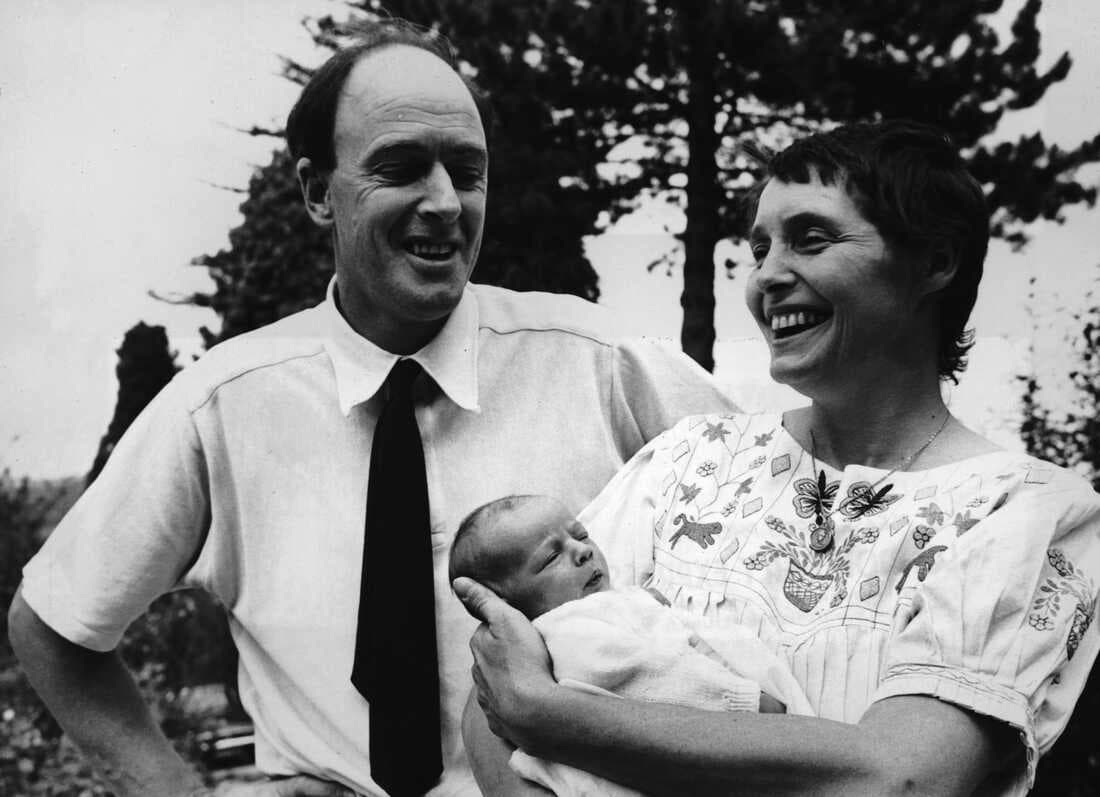

Roald Dahl and Felicity Ann Dahl

After graduation, Dahl took a position with the Shell Oil Company in Tanganyika, now Tanzania, and subsequently served as a fighter pilot in the Mediterranean during World War II. He suffered severe head injuries in a plane crash, and upon recovery, began his writing career publishing as short story in the Saturday Evening Post.

Paul Patterson: The Three Little Pigs, Op. 92c “Second Pig” (Rebecca Kenny, narrator; Magnard Ensemble)

Most of Dahl’s early writing was for adults. He specialized in wartime stories and macabre tales with surprise endings, or what the British call “a twist in the tail.” In a typical story, a wife kills her husband with a frozen leg of lamb, then cooks the murder weapon and serves it to police investigators. By that time, he was married to Hollywood actress Patricia Neal, and father of five children.

Paul Patterson: The Three Little Pigs, Op. 92c “Wolf creeps up” (Rebecca Kenny, narrator; Magnard Ensemble)

Every night, before the children went to bed, Dahl would make up bedtime stories. As he said in an interview, “inventing stories night after night was perfect practice for my trade. Children are highly critical, and they lose interest so quickly. You have to keep things ticking along. And if you think a child is getting bored, you must think up something that jolts it back. Something that tickles. You have to know what children like.”

Paul Patterson: The Three Little Pigs, Op. 92c “Piggie number three” (Rebecca Kenny, narrator; Magnard Ensemble)

One of his favourite ploys was to take revenge on cruel adults who had harmed children, and some adults started to object that he “showed little compassion or psychological penetration.” Dahl explained that adults might be disturbed by his books, “because they are not quite as aware as I am that children are different from adults. Children are much more vulgar than grownups. They have a coarser sense of humour. They are basically more cruel.”

Paul Patterson: The Three Little Pigs, Op. 92c “Picking up the telephone” (Rebecca Kenny, narrator; Magnard Ensemble)

Dahl would explain that children who wrote to him always picked out the most gruesome events as the favourite parts of the books…”They don’t relate it to life. They enjoy the fantasy… beastly people must be punished.”

Paul Patterson: The Three Little Pigs, Op. 92c “Confrontation with the Wolf” (Rebecca Kenny, narrator; Magnard Ensemble)

A literary critic writes, “the essence of Dahl is his willingness to let children triumph over adults. Children need the dark materials of fairy tales because they need to make sense—in a symbolic, displaced way—of their own feelings of anger, resentment, and powerlessness.

Paul Patterson: The Three Little Pigs, Op. 92c “The maiden smiles” (Rebecca Kenny, narrator; Magnard Ensemble)

Roald Dahl: Charlie and the Chocolate Factory

The child psychologist and scholar Bruno Bettelheim writes, “Children also benefit from learning about violence and brutishness in fairy tales, for it counters the widespread refusal to let children know that the source of much that goes wrong in our life is due to our natures—the propensity of all men for acting aggressively, a-socially, selfishly.”

Paul Patterson: The Three Little Pigs, Op. 92c “Ahh, Piglet” (Rebecca Kenny, narrator; Magnard Ensemble)

“Many fairy tales—and most of Dahl’s work—are complex narratives of wish fulfilment. They teach the reader, that a struggle against severe difficulties in life is unavoidable, and is an intrinsic part of the human existence.”

Paul Patterson: The Three Little Pigs, Op. 92c “Finale” (Rebecca Kenny, narrator; Magnard Ensemble)

Dahl seemingly gives children what they crave, “more pictures; more fantasies of mastery; more sly mockery of grouchy, boring adults; more visions of dizzying enjoyment.” His writing is certainly imaginative and exciting, and the turns towards the fantastic provides great entertainment value. For Dahl, “a writer for children must be a jokey sort of a fellow. He must like simple tricks and jokes and riddles and other childish things. He must be inventive. He must have a really first-class plot.”

Dahl religiously wrote four hours every day, always preferring to do his writing in an old red book in pencil. “A person must be a fool to become a writer,” he once said. “His only reward is absolute freedom. He has no master except his own soul, and that, I am sure, is why he does it.” As a literary critic wrote, “fairy tales inspire in children a sense that life “is not only a pleasure but an eccentric privilege.” Seemingly, Dahl’s stories not only indulge a child’s fantasies, “they replenish them.”

Martin Butler: Dirty Beasts, “The Tummy Beast” (Simon Callow, reader; New London Chamber Ensemble; Martin Butler, piano)

No animal is half as vile

As Crocky-Wock, the crocodile.

On Saturdays he likes to crunch

Six juicy children for his lunch

And he especially enjoys

Just three of each, three girls, three boys.

He smears the boys (to make them hot)

With mustard from the mustard pot.

But mustard doesn’t go with girls,

It tastes all wrong with plaits and curls.

With them, what goes extremely well

Is butterscotch and caramel.

It’s such a super marvellous treat

When boys are hot and girls are sweet.

At least that’s Crocky’s point of view

He ought to know. He’s had a few.

That’s all for now. It’s time for bed.

Lie down and rest your sleepy head.

Ssh! Listen! What is that I hear,

Galumphing softly up the stairs?

Go lock the door and fetch my gun!

Go on child, hurry! Quickly run!

No stop! Stand back! He’s coming in!

Oh, look, that greasy greenish skin!

The shining teeth, the greedy smile!

It’s Crocky-Wock, the Crocodile!

For more of the best in classical music, sign up for our E-Newsletter

Martin Butler: Dirty Beasts, “The Crocodile” (Simon Callow, reader; New London Chamber Ensemble; Martin Butler, piano)