Wilhelm Müller

The poet Wilhelm Müller (1794-1827) was famous in his lifetime for his verses in support of Greek struggle for emancipation from the Turks. Today, we mainly remember him for the highly popular song-cycles “Die schöne Müllerin,” and “Die Winterreise,” poems set to music by Franz Schubert. We tend to assume that “these works have maintained their fame not through any particular merit of the poems, but rather through the fact that a great musician was able to breathe life into these verses.” As Müller famously penned in his diary on 18 October 1815, “I can neither play nor sing, yet when I write verses I sing and play after all. If I could produce the tunes, my songs would please better than they do now. But courage! A kindred spirit may be found who will hear the tunes behind the words and give them back to me.” Müller was probably not thinking of Schubert—whom he never met—but he had no reason to sell himself short, as many of his poems abound with lilting musicality.

Das Wandern ist des Müllers Lust, | The miller’s delight is to wander |

Das Wandern! | to wander! |

Das muss ein schlechter Müller sein, | It must be a poor miller |

Dem niemals fiel das Wandern ein, | who never thought of wandering, |

Das Wandern. | of wandering. |

Franz Schubert: Die Schöne Müllerin, “Das Wandern” (Thierry Felix, baritone; Paul Badura-Skoda, piano)

Wilhelm Müller Complete Edition in 1830

Müller was the son of a shoemaker in Dessau and born on 7 October 1794. He discovered his poetic tendency during his early school days, and in 1812 he enrolled at the University of Berlin. His studies were interrupted by the political situation, and he volunteered for military service in the Prussian army. He fought against Napoleon at Lützen, Bautzen, Hanau and Kulm, but eventually resumed his university studies in 1815. He studied philology and history, and together with a group of friends, he published a volume of patriotic poems in 1816. Müller set out on a journey to Egypt to collect inscriptions for the Academy of Sciences in Berlin. On his journey he met a number of Greek intellectuals in Vienna, and he experienced the commedia dell’arte in Venice. For one, traveling stood at the core of his romantic sensibility, and wandering fostered his concern with the life and poetry of the common people. It is not surprising therefore that a substantial number of his poems established themselves as popular folksongs.

Carl Friedrich Zollner: Des Müllers Lust und Leid, Op. 6, No. 1 “Das Wandern ist des Müllers Lust” (Leipzig Radio Chorus; Jörg-Peter Weigle, cond.)

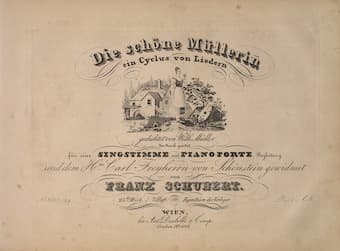

Schubert’s Die schöne Müllerin Diabelli Edition

Müller published the final version of the song-cycle “Die schöne Müllerin” in 1820. It consists of twenty-three poems framed by a prologue and an epilogue. It tells the story of a young miller who falls passionately but unrequitedly in love with a miller’s daughter. Schubert was immediately drawn to this poetic cycle, and his friend suggested that his settings “offer us deep insights into the composer’s innermost feelings.” However,

Schubert had not been the first composer to set these verses. That honor fell upon the Berlin composer Ludwig Berger. Already in 1816, a group of art lovers put on a brief play at the Berlin home of Councilor Friedrich August von Staegemann. That play, with interspersed songs, told the story of how the lovely maid of the mill is courted by three men, a young miller, a gardener and a hunter. The hunter eventually wins the day, and five of the song texts are poems by Wilhelm Müller. In all, Berger selected ten poems, set them to music and published them in 1818 under the title Songs from the Liederspiel “Die schöne Müllerin.”

Ludwig Berger: Songs from the Liederspiel “Die schöne Müllerin,” No. 9 “Müllers trockne Blumen” (Markus Schäfer, tenor; Tobias Koch, piano)

Ihr Blümlein alle, | All the flowers |

Die sie mir gab, | she gave to me, |

Euch soll man legen | should be placed |

Mit mir ins Grab. | into the grave with me. |

|

|

Wie seht ihr alle | Why do you look at me |

Mich an so weh, | so sorrowful |

Als ob ihr wüsstet, | As if you knew |

Wie mir gescheh’? | what has happened to me. |

—————————————————————————————————————————–

Und wenn sie wandelt | And if she should walk |

Am Hügel vorbei, | past my grave |

Und denkt im Herzen: | and feels in her heart |

„Der meint’ es treu!“ | “His love was true” |

|

|

Dann Blümlein alle, | Then, all you flower |

Heraus, heraus! | Come forth, come forth! |

Der Mai ist kommen, | May has come, |

Der Winter ist aus. | The winter is over. |

Franz Schubert: Die Schöne Müllerin, “Trockne Blumen” (Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau, baritone; Gerald Moore, piano)

Ludwig Berger

Following a minor illness in 1824, Schubert composed a set of variations for piano and flute to more fully explore the emotional world of the “Withered flowers.” A friend reports, “Schubert now keeps a fortnight’s fast and confinement. He looks much better and is very bright, very comically hungry, and he writes quartets and German dances and variations without number.” Neither unashamedly virtuosic nor consistently poetic, the set opens with an introduction evoking the mood of a funeral march. Of course, in the tragic story of unrequited love, the narrative has reached a point where death has become immanent and overpowering. A scholar writes, “In so many other cases a rugged exterior impedes access to a work of art; with Schubert it is often a gentle, pleasing surface that conceals its profundity.”

Franz Schubert: Introduction and Variations on “Trockne Blumen” from Die schöne Müllerin, Op. 160 (Chiara Tonelli, flute; Silka Avenhaus, piano)

Müller’s cycle tells of the obsession of a wanderer with the beautiful miller maid named Rose. She wants nothing to do with the poor lad, and instead gives all her attention to a hunter. The wanderer is inconsolable, and in the end drowns himself in a stream. In Müller’s narrative, following the suicide of the protagonist, Rose also drowns herself in the brook. In Ludwig Berger’s setting, however, Rose does not commit suicide and goes on living. Scholars have put forth a possible explanation for Berger’s retouching of the poetry. “In his unreciprocated love for Luise Hensel—Fanny Mendelssohn-Hensel’s sister-in law—Berger identified with the miller’s pain and altered the drama.” We do know that Berger was head over heels in love with 18-year old Luise. However, Luise concerted to Catholicism and elected to live a chaste life. Berger was predictably devastated, but he did not take his own life.

Ludwig Berger: Songs from the Liederspiel “Die schöne Müllerin,” No. 2 “Des Müllers Blumen” (Markus Schäfer, tenor; Tobias Koch, piano)

Fanny Mendelssohn-Hensel

Among the young art lovers who put on that Singspiel in 1816, were Fanny Mendelssohn and her future husband Wilhelm Hensel, who played the role of the hunter. Fanny placed herself in the role of “Rose,” and Berger’s setting had an important influence on her early songs. Scholars have suggested, “Fanny Mendelssohn’s settings are thus openly in debt to her teacher, yet they show signs of her emerging personal style.” Similarities in their settings include the overall structure, a “piano accompaniment that frequently doubles the vocal line, cadential extensions, and a clearly defined key center.”

Fanny Mendelssohn-Hensel: “Des Müllers Blumen” (Roswitha Müller, mezzo-soprano; Kelvin Grout, piano)

Am Bach viel kleine Blumen stehn | Many small flowers stand by the brook |

Aus hellen blauen Augen sehn; | They look out with their bright blue eyes |

Der Bach, der ist des Müllers Freund | The brook is the miller’s friend |

Und hellblau Liebchens Auge scheint | And light blue shine the eyes of my darling |

Drum sind es meine Blumen. | Therefore, these are my flowers. |

In Schubert’s setting, the young miller’s outpouring is matched with a lyrical arpeggio pattern and a gently rocking rhythm. There is no explicit indicated postlude, which is unusual in most of Schubert. Instead, accompanists often choose to simply repeat the introduction.

Franz Schubert: Die schöne Müllerin, Op. 25 “Des Müllers Blumen” (Thomas Quasthoff, bass; Justus Zeyen, piano)

Fanny Mendelssohn-Hensel in 1836

“Der Neugierige” (The Curious One) presents the complimentary poles of introspective searching and outward commentary. Nature provides no answers, so the young miller again turns to the brook. “The intimate charm of the poem lies in the almost audible silence which greets the boy’s questionings. It is characteristic of Müller’s poetic imagination, as it is conceived in the form of a strict polarity—the answer must be either yes or no. This polarity encompasses all possibilities of happiness or unhappiness.” In Schubert’s setting, this expressive through-composed song opens with a cleverly executed musical question in the accompaniment, a rising pattern ending on a diminished chord. In the contemplative second section, the brook is represented, as always, by flowing broken triads.

Franz Schubert: Die Schöne Müllerin, “Der Neugierige” (Daniel Behle, tenor; Sveinung Bjelland, piano)

Fanny Mendelssohn set the same poem to music in 1823. She was only 18, and we know that she personally knew Wilhelm Müller. On first glance, these early songs appear simple in their strophic structure and without any particular vocal challenge. It takes closer inspection, however, to note her highly developed musical skill and her sensitivity to the poem. In her setting, Fanny wasn’t thinking in terms of the overall trajectory of the poetic cycle, but preferred an imaginative close reading of individual poems. Fanny does adhere to the strict song writing style of the Second Berlin Liederschule, a compositional aesthetic pioneered by her composition teacher Carl Friedrich Zelter. However, she quickly outgrew her teacher’s conception and her harmonic and melodic vocabulary became much more sophisticated in a short period of time. Various other settings by a substantial number of frequently minor composers have been crafted. This seems hardly surprising, as scholars have suggested, “This cycle exemplifies the lyric quality of Müller’s poetry in its purest form.”

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter

Fanny Mendelssohn-Hensel: “Der Neugierige” (Kobie van Rensburg, tenor; Kelvin Grout, piano)