Antoine Watteau: Pleasures of Love

When Paul Verlaine’s Fêtes galantes was published in 1869, Théodore de Banville penned the following critique in Le National of 19 April. “There are art-crazed minds, enamored of poetry more than of nature, who want Amintes and Cydalises deftly coiffed and dressed in long satin robes, purple- and rose-colored. To those I would say: take along the Fêtes galantes by Paul Verlaine, and this little magician’s book will make you feel suave, harmonious and deliciously sad: all of the ideal, enchanted world of the divine master of amorous plays, the great, sublime Watteau.” For a good many critics and composers, the pictorial dimension of Verlaine’s poetry became a much-valued focal point. And the “Mandoline,” with its implied pictorial and musical dimensions became an all-time favourite.

The givers of serenades

And the lovely women who listen

Exchange insipid words

Under the singing branches.

There is Thyrsis and Amyntas

And there’s the eternal Clytander,

And there’s Damis who, for many a

Heartless woman, wrote many a tender verse.

Their short silk coats,

Their long dresses with trains,

Their elegance, their joy

And their soft blue shadows,

Whirl around in the ecstasy

Of a pink and grey moon,

And the mandolin prattles

Among the shivers from the breeze.

Gabriel Fauré: 5 Melodies de Venise, Op. 58 – No. 1 Mandoline (Carl Ghazarossian, tenor; David Zobel, piano)

Gabriel Fauré

Following Fauré’s death, his good friend Paul Dukas wrote. “Those who had the joy of sharing Fauré’s intimacy know how faithfully his art reflected his being – to the extent that his music at times would seem to them the harmonious transfiguration of his own exquisite charm. Others did their utmost to rise above themselves or, if they collaborated with a poet, to surpass that collaborator. Fauré, with a unique grace, without constraint, gathers every external impression back into his inner harmony. Poems, landscapes, sensations that arise from the spur of the moment or the fleeting wave of memories – whatever sources his music springs from, it translates above all his own self according to the varied moods of the most admirable sensibility.” And his student Charles Koechlin remarked “his music does not adapt itself to its subject, but rather, it constitutes the essence of it; a magic mirror, his music becomes the subject itself.” His setting of “Mandoline” is immediately accessible with repeated motives sounding in the first two verses. Unsurprisingly, the piano accompaniment is reminiscent of a mandolin, but as the singer is acting as a narrator rather than a character in the scene, Fauré’s setting implies a certain degree of emotional separation from the text.

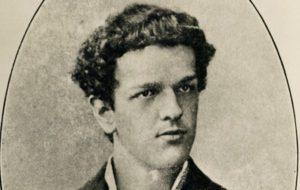

Claude Debussy, 1879

Claude Debussy wrote “Mandoline” around 1883. It is one of the first Verlaine texts he set to music. It is a work of juvenilia, but Verlaine’s text is precisely what would have appealed to him at this time in his life. Debussy’s amorous ventures were well known, and the light-hearted text pokes fun at wild exchanges of vows, and luxuriates in a good lifestyle. The lively and elegant, yet energetic pursuit is not predatory, but a “reaction to instincts that are far from desperate.” The idea of using the piano as a mandolin substitute is not a new concept, but Debussy introduces a new realism in the opening call to attention. The opening fifths allows for limitless possible continuations, and the initial vocal line sets out wonderfully floating chromatic phrases that won’t be repeated until the final verse. Characteristically, the ending simply fades away and is culminated in a repeat of the opening call to attention. As a critic wrote, “Here for the first time Debussy gave some intimation of what his piano parts would soon become.”

Josef Szulc: Mandoline (Carl Ghazarossian, tenor; David Zobel, piano)

Poldowski (Régine Wieniawski)

In Art poétique Verlaine passionately describes his artistic vision. “Music before everything, and for that reason, prefer lines of an uneven number of syllables, vaguer and dissolving better into air, with nothing in them that is weighty or comes to a stop. You must also choose your words with a certain negligence: nothing dearer than the grey song where the indeterminate and the exact are joined. It’s like beautiful eyes behind a veil, the great quivering light of noon; it’s like, in a warmish autumn sky, the blue heap of bright stars! For we still want shades, not plain color, nothing but shades! Oh, but a subtle shade alone weds dream to dream and the flute to the horn.”

Antoine Watteau: The Embarkation for Cythera

The shades of pleasure and courtship in “Mandoline” inspired not only the composer and conductor Josef Szulc, it also resonated with Régine Wieniawski who worked under the professional pseudonym Poldowski. Daughter of the Polish violinist and composer Henryk Wieniawski, Poldowski was a gifted composer of songs, and her style shows strong influences of Claude Debussy. And Paul Verlaine was certainly her favorite poet; in all, she set 22 of his texts.

Poldowski: Mandoline (Carl Ghazarossian, tenor; David Zobel, piano)