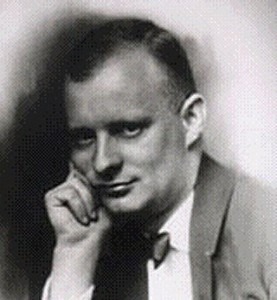

Paul Hindemith was a precocious musical talent. Whatever he touched, he almost instantaneously mastered. He started violin lessons at an early age and was admitted to the Frankfurt Conservatory at age 12. He soon became an accomplished performer on several instruments, most notably the clarinet and the piano, and also the violin and viola. At age 19 he was appointed first violinist of the Frankfurt Opera Orchestra. Yet even before he entered the Conservatory, Hindemith had already written his first compositions. Some of these pieces were performed during his Conservatory days and are heavily influenced by Johannes Brahms.

Paul Hindemith was a precocious musical talent. Whatever he touched, he almost instantaneously mastered. He started violin lessons at an early age and was admitted to the Frankfurt Conservatory at age 12. He soon became an accomplished performer on several instruments, most notably the clarinet and the piano, and also the violin and viola. At age 19 he was appointed first violinist of the Frankfurt Opera Orchestra. Yet even before he entered the Conservatory, Hindemith had already written his first compositions. Some of these pieces were performed during his Conservatory days and are heavily influenced by Johannes Brahms.

Johannes Brahms, String Quartet in C minor, Op. 51, No. 1, Movement 1

In one way or another, Johannes Brahms dominated the musical discourse in the early 20th century. His musical style was frequently described as the logical union of Bach’s contrapuntal art and Beethoven’s formal perfection. Concordantly, Arnold Schoenberg questioned this conception of Brahms as a bastion of musical conservatism in a celebrated Radio address entitled “Brahms the Progressive.” Schoenberg suggested that Brahms “blurred the boundary between theme and development.” As such, a small musical idea organically grows to generate the overall form. Schoenberg’s notion of “developing variation” not only justified his own compositional style, it also suggested that it was Brahms and his chamber music that prepared the way for the radical changes in musical language at the turn of the 20th century. Be that as it may, young Hindemith and a whole host of aspiring composers clearly attempted to come to terms with the music of Johannes Brahms.

Paul Hindemith, String Quartet in C major, Op. 2, Movement 1

However, in 1917 Hindemith was ready to break away from conservatory routine suggesting, “I want to write music, not song forms and sonata forms…I can’t talk seriously with anyone at the conservatory because none of them has any ideals left. Their whole art has become far too much craft!” In 1917, he was also called up for military service and stationed close to the front line. His commanding officer asked him to form a string quartet to give private concerts. During a performance of Debussy’s String Quartet, news reached the front that Debussy had died. Hindemith wrote, “We realized for the first time that music is more than style, technique and the expression of personal feelings. Music stretched beyond political boundaries, national hatreds and the horrors of war. I have never understood so clearly as then what direction music must take.”

Claude Debussy, String Quartet in G minor, Op. 10, Movement 1

Debussy’s death and the devastation of WW1 caused a traumatic loss of identification with the prewar musical values that had been central to Hindemith’s early education. “The old world just exploded,” Hindemith wrote to a friend. Determined to break away from German art music, he briefly turned towards provocative and aggressive novelty that was designed to outrage German audiences. Hindemith’s reputation was established with three one-act operas, among them the burlesque Das Nusch-Nuschi, premiered in Stuttgart in 1921. Based on a Burmese marionette play that scandalously satirized Tristan and Isolde — actually it parodies almost the entire compositional canon of the turn of the nineteenth century — features one man having sex with four women, all of whom are married to other men, while the orchestra plays suggestive dances. It infamously quotes from Tristan and Isolde in the castration episode in the third scene.

Debussy’s death and the devastation of WW1 caused a traumatic loss of identification with the prewar musical values that had been central to Hindemith’s early education. “The old world just exploded,” Hindemith wrote to a friend. Determined to break away from German art music, he briefly turned towards provocative and aggressive novelty that was designed to outrage German audiences. Hindemith’s reputation was established with three one-act operas, among them the burlesque Das Nusch-Nuschi, premiered in Stuttgart in 1921. Based on a Burmese marionette play that scandalously satirized Tristan and Isolde — actually it parodies almost the entire compositional canon of the turn of the nineteenth century — features one man having sex with four women, all of whom are married to other men, while the orchestra plays suggestive dances. It infamously quotes from Tristan and Isolde in the castration episode in the third scene.

Paul Hindemith, Das Nusch-Nuschi, Op. 20

With the premier performances of his operatic triptych, which also included Mörder, Hoffnung der Frauen (Murder, Hope for Women) and Sancta Susanna, exploring the sexual fantasies of a young nun, Hindemith gained a reputation as a prodigious but unreflective, almost naïve talent which indulged a “rather puerile propensity for transgressing bourgeois conventions.” Music history records that it took Hindemith almost a decade to live down the reputation based on these works. In the meantime, Hindemith continued to explore and incorporate various international musical styles, including the music of Béla Bartók, Igor Stravinsky, Darius Milhaud and influences from Jazz and popular music. I tell you more about that in our next episode.

More Inspiration

-

Seven Works Dedicated to Brahms Explore the friendships and musical tributes that honored Brahms

Seven Works Dedicated to Brahms Explore the friendships and musical tributes that honored Brahms -

Creating a New Chopin Explore classical music's transformation in popular genres

Creating a New Chopin Explore classical music's transformation in popular genres - Reflections of the Past: George Rochberg’s Carnival Music Listen to how he blends jazz, blues, and classical quotations

- Smetana’s Musical Postcards

The Albumblätter of a Young Romantic Music composed for his wife, friends and students!