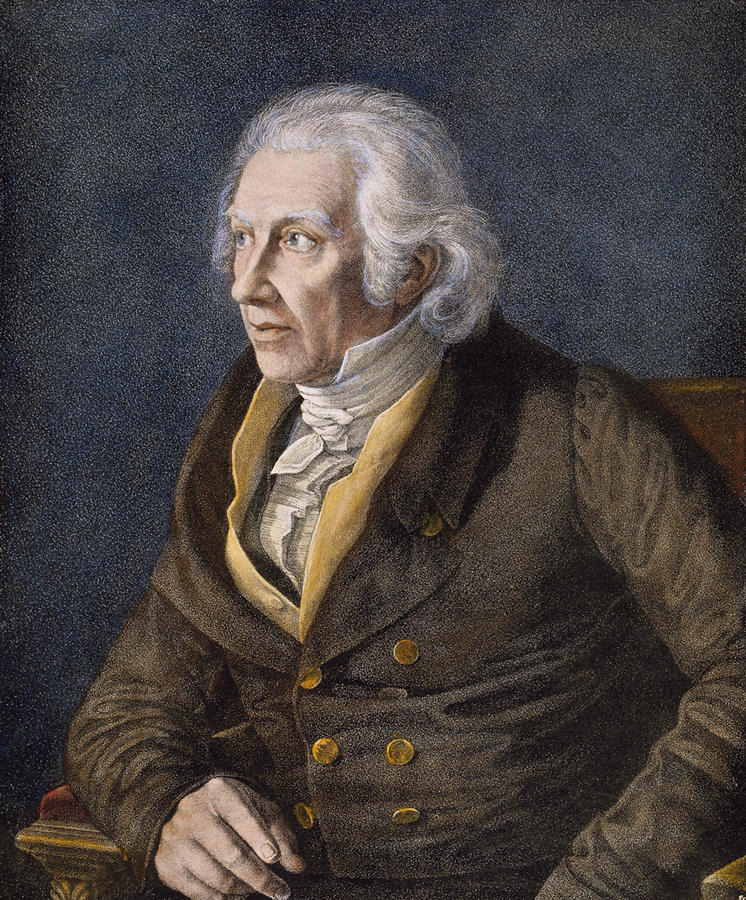

Carl Friedrich Zelter Credit: http://images.fineartamerica.com/

Listen, for example, to Carl Friedrich Zelter’s setting of Goethe’s action poem “Erlkönig.” Zelter (1758–1832) was a generation older than Schubert. The voice is the lead. The piano follows, adding colour as needed, but not providing anything further.

Zelter: Erlkönig (Han Joög Mammel, tenor; Ludwig Holtmeier, piano)

When we listen to Carl Loewe’s setting, we hear the piano come to the fore a bit more – high echoes for the Erlkönig ‘s voice are the most prominent colouring provided by the piano. Loewe (1796–1869) was born a year before Schubert.

Loewe: 3 Balladen, Op. 1, No. 3: Erlkönig (Hermann Prey, Baritone; Günter Weissenborn, piano)

When we get to the most familiar setting, that by Schubert (1797-1828), the piano has become a truly supporting character: the horse that the father is riding.

Schubert: Erlkönig , Op. 1, D. 325 (Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau, baritone; Gerald Moore, piano)

Schubert – Der Erlkönig (complete version.)

The piano/horse starts at a dead run and you can even hear the father’s pull on the reins as he directs its headlong dash. Each voice: narrator (for the first and last verse), the father (a solid middle tone), the child (a high pleading tone), and the Erlkönig (a light enticing voice) has its place in the story but it’s the piano that drives it forward, pushing towards the salvation offered by the distant courtyard. Although the son is not mentioned as being ill at the start of the poem, by the end, the gasping child has been hurt by the Erlkönig and dies in his father’s arms. The piano/horse stops, the narrator announces the child’s death and the piano has in the last word with a V-I ending. Throughout the setting, it is the piano that has provided us with the background not in the poem – the desperation of the ride, the wild night, and then the final sorrow.

Carl Loewe Credit: http://www.bach-cantatas.com/

Listen, for example, to his cycle Frauenliebe und –leben. The last piece in the cycle, No. 8. ‘Nun hast du mir den ersten Schmerz getan’ (Now you have hurt me for the first time,) is the woman’s lament at her husband’s death. Through the song, the piano is barely visible – a few crashing chords for emphasis. At the end, however, the unnamed woman decides what do with her life.

| ….Ich zieh mich in mein Innres still zurück, Der Schleier fällt, Da hab ich dich und mein verlornes Glück, Du meine Welt! | …I withdraw silently into myself, the veil falls, there I have you and my lost happiness, O you my world! |

And the piano tells us what happens in its post-commentary: she withdraws into herself, there’s perhaps a hint of taking to the convent in its stately hymn-like voicing, and then it all fades away, just as she will.

Schumann: Frauenliebe und –leben, Op. 42, No. 8: Nun hast du mir den ersten Schmerz getan (Sarah Connolly, mezzo; Eugen Asti, piano)

And this is the contribution of Schumann. In continuing the developments in the lied made by Schubert, Schumann can’t let any song end without the commentary by the piano. This is just as true in the works produced in his first Liederjahr of 1840 and those of his second Liederjahr a decade later. It is these commentaries that help the listener place the poem into the larger world and to put the song setting into context.