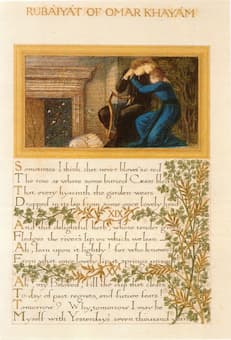

Calligraphic manuscript page with three of

FitzGerald’s Rubaiyat. Calligraphy by William Morris,

illustration by Edward Burne-Jones (1870s)

In 1859, English poet and writer Edward FitzGerald published the first translation of what he called the Rubáiyát of Omar Khayyám. Coming from one of the wealthiest families in England, FitzGerald could do as he wished and one of the things he wished was to study Persian literature at Oxford in 1853 with Professor Edward Cowell.

In 1857, Cowell discovered a set of quatrains (rubāʿiyāt) attributed to Omar Khayyam (1048–1131) in the library of the Asiatic Society. He sent them to FitzGerald and his first translation appeared in a pamphlet in January 1859. It came and went, seemingly without notice, until the poet Dante Gabriel Rossetti and then Charles Algernon Swinburn discovered it. In 1868, FitzGerald published a larger revised second edition, and in 1872, a third edition. By the 1880s, the work was universally famous.

American composer Arthur Foote took on the cult on Omar Khayyam in his Op. 41 piano cycle: Five Poems after Oman Khayyam. In 1900, he revised the piano pieces to create Four Character Pieces after the Rubáiyát of Omar Khayyám, Op. 48. These romantic views of the poems are underscored by the fact that each movement is headed with the apposite quatrain for the movement.

A little romantic jewel, the work is built around the atmospheric qualities of certain instruments. The first movement, and its chromatically inflected clarinet, is headed by this verse from the Rubáiyát:

Iram indeed is gone with all his Rose,

And Jamshyd’s Sev’n-ring’d Cup where no one knows;

But still a Ruby kindles in the Vine,

And many a Garden by the Water blows.

Iram was a city on the Arabian Peninsula, known for its fruit trees and flowers, but its wickedness led to its destruction by God. Jamshyd (Jamshid) was a mythical king of Persia whose seven-ring cup enabled the viewer to see all seven corners of the world and so divine the future. The city is lost, the cup is lost and all things may perish, but nature may continue.

Arthur Foote: 4 Character Pieces after the Rubaiyat of Omar Khayyam, Op. 48 – No. 1. Andante comodo (Seattle Symphony Orchestra; Gerard Schwarz, cond.)

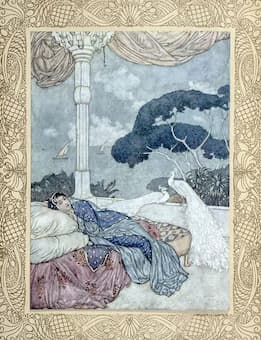

Edmund Dulac: Illustration for Rubáiyát of Omar Khayyám (1909)

The driving second movement seems close to nationalistic works such as Brahms’ Hungarian Dances or Dvořák’s Slavonic Dances. Two poems illustrate this movement:

They say the Lion and the Lizard keep

The Courts where Jamshyd gloried and drank deep:

And Bahrám, that great Hunter – the Wild Ass

Stamps o’er his Head, but cannot break his Sleep

And then, for the slower middle section:

Yet ah, that Spring should vanish with the Rose!

That Youth’s sweet-scented manuscript should close!

The Nightingale that in the branches sang,

Ah whence, and whither flown again, who knows!

Jamshid, as in the first movement, makes another appearance. This mythical king is said to have ‘inspired the arts of civilization.’ Bahram Gur, a shah in the Sasanian Empire (420-438), lost his life in a swamp pursuing a wild ass.

The Lion and the Lizard symbolize courage and trickery, opposing qualities in a leader.

Both the fast and slow sections use the same rhythm, but to different effects.

Arthur Foote: 4 Character Pieces after the Rubaiyat of Omar Khayyam, Op. 48 – No. 2. Allegro deciso – Più moderato (Seattle Symphony Orchestra; Gerard Schwarz, cond.)

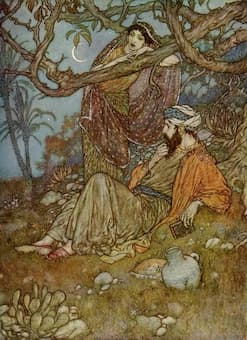

The third movement is headed by what is probably the best-known verse of the Rubáiyát:

The third movement is headed by what is probably the best-known verse of the Rubáiyát:

A Book of Verses underneath the Bough,

A Jug of Wine, a Loaf of Bread – and Thou

Beside me singing in the Wilderness –

Oh, Wilderness, were Paradise enow!

The harp comes to the fore in this movement. One writer reminds us that, although referred to in the text is Omar the tent-maker, or Omar the tent-maker’s son, in actuality, Omar Khayyam was the son of a physician and was himself an astronomer and mathematician at the court of Malik-Shah in Esfahan. In this movement, there is the balance between work and leisure – sitting out under the trees with everything in the world at hand.

Arthur Foote: 4 Character Pieces after the Rubaiyat of Omar Khayyam, Op. 48 – No. 1. Andante comodo (Seattle Symphony Orchestra; Gerard Schwarz, cond.)

The last movement speaks of the future – the moon rises and oversees our lives. The movement is in 6/8 time, but Foote speeds us and slows us through the movement. Time may be going on, but it’s never the same from day to day. The movement is headed with:

Yon rising Moon that looks for us again –

Yon rising Moon that looks for us again –

How oft hereafter will she wax and wane;

How oft hereafter rising look for us

Through this same Garden – and for one in vain!

The middle section carries this verse:

Waste not your Hour, nor in the vain pursuit

Of This and That endeavor and dispute;

Better be jocund with the fruitful Grape

Than sadden after none, or bitter, Fruit.

The instrument of focus in this movement are the horns, which makes their way through a floating melodic line. In the middle section, it’s the oboe that carries the line. When the first section returns at the end, it’s the bassoon that has the melody.

Arthur Foote: 4 Character Pieces after the Rubaiyat of Omar Khayyam, Op. 48 – No. 1. Andante comodo (Seattle Symphony Orchestra; Gerard Schwarz, cond.)

Taking a 12th-century verse and setting it into stylized English verse, FitzGerald prepared the way for several decades worth of Middle Eastern interest. We should probably consider that Rudolph Valentino’s movie versions of an Arabic sheikh came from the verses that FitzGerald had translated so many decades earlier.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter