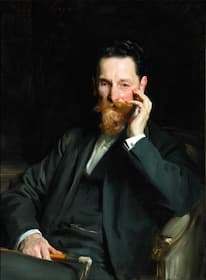

John Singer Sargent: Joseph Pulitzer (1905)

The Pulitzer Prize was first awarded in 1917, following instructions left by newspaper publisher Joseph Pulitzer in his 1904 will. The Pulitzer Prize in Music was established in 1943 after being converted from an annual scholarship for “the student of music in America whom the Advisory Board shall deem the most talented and deserving, in order that he may continue his studies with the advantage of European instruction.’ You see the problem already: out of all the music students in the country, how would you determine the most ‘talented and deserving’? In 1943, the definition for the prize was changed to recognize works of ‘music in its larger forms as composed by an American.’ Again, more discussion over what ‘in its larger forms’ meant.

The Pulitzer Prize Medal

Over the years, the definition has changed and now it’s ‘For distinguished musical composition by an American that has had its first performance or recording in the United States during the year.’ The genre has expanded from purely classical music to encompass jazz, opera, choral, musical theater, movie scores and other forms of musical excellence. Critics of the Prize, including some award winners, think that the Prize has become one given by composers on the jury to other composers and that academic music has been recognized too much. On the other hand, some critics regard the inclusion of musical and movie score music as diluting the award to include works of a much lower artistic level.

We should be aware that the rules for the Pulitzer Prize for Music changed over time. The Prize is awarded for the previous year’s work, i.e., the 1943 prize was for work done in 1942.

The Rules:

1943-1963 (no prize was awarded in 1964 and 1965)

For distinguished musical composition in the larger forms of chamber, orchestral or choral music, or for an operatic work (including ballet), performed or published during the year by a composer of established residence in the United States.

1966-1989

For distinguished musical composition by an American in any of the larger forms including chamber, orchestral, choral, opera, song, dance, or other forms of musical theatre, which has had its first performance in the United States during the year.

1999-2003

For distinguished musical composition of significant dimension by an American that has had its first performance in the United States during the year.

2004 – Now

For distinguished musical composition by an American that has had its first performance or recording in the United States during the year.

In this survey of the Pulitzer Prizes in Music winners, we’ll look at nearly 80 years of music composition in the US.

The 1940s

William Schuman

The first Pulitzer Prize in Music was awarded to William Schuman’s Secular Cantata No. 2: A Free Song. Written in the middle of WWII, the work sets the words of the American Civil War’s most famous pacifist, Walt Whitman, from his poetry collection Drum-Taps (1865) to create a work that one writer said, ‘expresses only a desire for freedom for all…’

William Schuman: A Free Song, “Secular Cantata No. 2” – Part I: Look Down, Fair Moon (Ryan J. Cox, baritone; Grant Park Chorus; Grant Park Orchestra; Carlos Kalmar, cond.)

Howard Hanson

The 1944 Prize was awarded to Howard Hanson for his Symphony No. 4, Op. 34, Requiem. Dedicated to the composer’s father, who had recently died, the work takes the movement names from the Requiem Mass: Kyrie, Requiescat, Dies irae, and Lux aeterna. The work is considered one of the highlights of American Romanticism.

Howard Hanson: Symphony No. 4, Op. 34, “Requiem”: III. Dies irae: Presto (Seattle Symphony Orchestra; Gerard Schwarz, cond.)

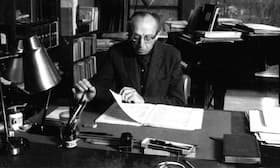

Aaron Copland

The 1945 award was given to the one work in the entirety of the Pulitzer Prize for Music that most people will recognize, although they’ve rarely seen the work the music was written for. Aaron Copland’s ballet Appalachian Spring is now best known in its version as an orchestral suite. Commissioned by the choreographer and dancer Martha Graham, the ballet is a celebration of American pioneers of the 19th century that became a parable about America and its move west during the 19th century.

Aaron Copland: Appalachian Spring Suite (Nashville Chamber Orchestra; Paul Gambill, cond.)

Leo Sowerby

Leo Sowerby’s The Canticle of the Sun sets an English translation of St Francis of Assisi’s religious song of the same name and was awarded the 1946 Pulitzer Prize for Music. Despite Sowerby’s skill as a choral composer, the work has been performed relatively few times.

Leo Sowerby: Canticle of the Sun – O most high … (Grant Park Chorus; Grant Park Orchestra; Carlos Kalmar, cond.)

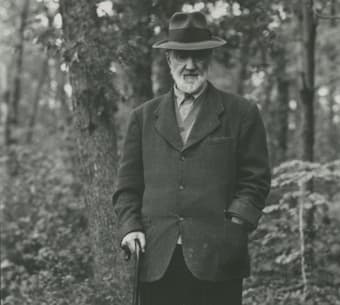

Charles Ives

The 1947 Prize winner, Charles Ives’ Symphony No. 3, The Camp Meeting, had its start in three organ works he wrote around 1903 while organist at New York’s Central Presbyterian Church. The works are now lost, but they are integral to this 1904 work. The title of the symphony The Camp Meeting, refers to the open-air services that the Central Presbyterian Church ran every year. How did this piece written in 1904, the last year that Ives was a professional musician, become the 1947 prize winner? The 1904 score was never performed, the revision done in 1909 was lost by the conductor Walter Damrosch, the second copy of the 1909 version disappeared when conductor Gustav Mahler took it back to Vienna (and it’s never been seen again). Finally, American composer Lou Harrison got the unrevised original 1904 copy directly from Charles Ives and it was prepared for performance at Carnegie Hall. Since the 1904 score was first published in 1946, it was eligible for consideration by the 1947 Pulitzer Committee and won.

Charles Ives: Symphony No. 3, The Camp Meeting – I. Old Folks Gatherin’ (Melbourne Symphony Orchestra; Andrew Davis, cond.)

Walter Piston

Another Symphony No. 3 was the 1948 prize-winner, composed by Walter Piston, who taught composition at Harvard University from 1926 until his retirement in 1960. The work was commissioned by the Koussevitzky Music Foundation, and it was given its premiere performance by the Boston Symphony Orchestra conducted by Koussevitzky in 1948. After graduating from Harvard in 1924, he went to Paris to study with Nadia Boulanger for 2 years. Unlike his contemporaries (such as Gershwin, for example), he did not try to incorporate popular music, such as jazz, into his works, but sought to define a classical American music, using traditional forms and harmony while still maintaining a distinct and American voice.

Walter Piston: Symphony No. 3 – I. Andantino (Harvard-Radcliffe Orchestra; James Yannatos, cond.)

Virgil Thomson

We close the 1940s with the 1949 winner, Virgil Thomson’s music for the ‘docu-fiction’ film Louisiana Story. The film, about a poor Cajun family who becomes a wealthier Cajun family after oil is found on their land, uses a boy and his pet racoon as the center of the story. Thomson’s Prize remains the only Pulitzer awarded for a film score.

Virgil Thomson: Louisiana Story Suite – II. Chorale (Philadelphia Orchestra; Eugene Ormandy, cond.)

As the 1940s progresses, we can see the Pulitzer Music Committee becoming braver and braver in their choices. Film music certainly wasn’t considered on par with music written for symphony orchestras in 1943, but by 1949, the committee opened its mind to it. Adding the 1904 work by Ives was wonderful recognition of a composer who had been influential but not to his own generation.

Now, the 1950s!

1950s

Gian Carlo Menotti © Wikipedia

In the 1950s, for the first time, the Pulitzer Prize was expanded to include more than just symphonic (orchestral and ballet) music and film scores. Now opera came under consideration and was awarded 4 Prizes over the decade.

The first opera was awarded the Pulitzer Prize in Music in 1950. Gian Carlo Menotti won it for The Consul, his first full-length opera. In an unnamed European totalitarian country, a political dissident, his wife, their child, and his mother try to escape the country. While the dissident is in hiding, his family try to get exit visas, but without success. The mother and child die, and the wife kills herself just as her husband returns and is captured by the police. The opera was noted for its topicality about the difficulties people were having while getting into the US. In this scene, Magda, gassing herself to death, has visions of all the bureaucrats who have stymied her, the other people she’s met in line, and how to explain the child’s death to her husband.

Gian Carlo Menotti: The Consul – Act III, Scene 2: Lo, Death’s frontiers are open (Susan Bullock, Magda Soel; John Horton Murray; Magician; Jacalyn Kreitzer, Mother; Victoria Livengood; Secretary; Malin Fritz, Vera Boronel; Louis Othey, John; Spoleto Festival Orchestra; Richard Hickox, cond.)

Douglas Moore

In 1951, Douglas Moore, music professor at Columbia University since 1926, won for his opera Giants in the Earth, about Scandinavian settlers in the American Midwest.

Gail Kubik © discogs.com

The 1962 Pulitzer was awarded to Gail Kubik for his orchestral work Symphony Concertante. The work, for trumpet, viola, piano, and orchestra and was praised by the Pulitzer committee for its originality and exuberance. The work was based on an earlier film score he did for the movie “C”-Man (1949) about US Treasury agents discovering a scheme for smuggling and murder.

Gail Kubik: Symphony Concertante – III. Fast, with energy

In 1953, for the first, but not the last time, there was no Pulitzer Prize in Music awarded.

Quincy Porter © American Composers Alliance

Quincy Porter, who taught at Yale University, received the Pulitzer in 1954 for his Concerto Concertante for two pianos and orchestra. The work was described as ‘affectively compelling, orchestrally luminous, and contrapuntally active; cooperative rather than competitive….’ The work was commissioned by the Louisville Orchestra. The work is in one movement, with a rather slow start before an electrifying Allegro section where the two keyboards enter into dialogue with the orchestra.

Quincy Porter: Concerto Concertante

Gian Carlo Menotti became the first double winner with the awarding of the Prize in 1955 for his opera The Saint of Bleeker Street. Set in the Little Italy section of New York City, the opera counters a simple woman with stigmata, Annina, who her neighbors believe to be a saint, with her protective but atheist brother, Michele, who thinks she needs to be hospitalized. The final scene, where Annina takes her vows to become a nun against her brother’s protest, ends in Annina’s collapse and death.

Gian Carlo Menotti: The Saint of Bleecker Street – Act III, Scene 2: Annina, Annina! (Timothy Richards, Michele; Vitali Rozynko, Salvatore; John Marcus Bindel, Don Marco; Amelia Farrugia, Maria Corona; Sandra Zeltzer, Carmela; Yvonne Howard, Assunta; Spoleto Festival Choir; Spoleto Festival Orchestra; Richard Hickox, cond.)

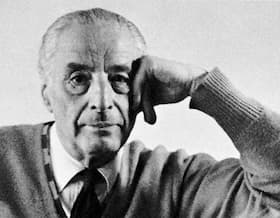

Ernst Toch © Britannica

Ernst Toch, started off with works that were pastiches of Mozart and ended up being one of the most influential composers in America. In his third symphony, which won the Pulitzer in 1956, he returned to the late Romantic style he’d cultivated in his early years as a composer. At the same time, the drama of his film music is also present in the symphony.

Ernst Toch: Symphony No. 3

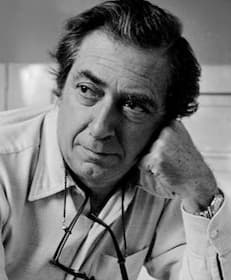

Norman Dello Joio © Wikipedia

Norman Dello Joio started studying the piano at age 4 under his father, himself an organist and pianist, as well as being a part-time composer and vocal coach to many opera singers at the Metropolitan Opera. He studied at Juilliard and with Paul Hindemith, who encouraged him to find his own way, rather than following the atonal style of the day. His Meditations on Ecclesiastes was the 1957 Prize winner.

Dello Joio: Meditations on Ecclesiastes

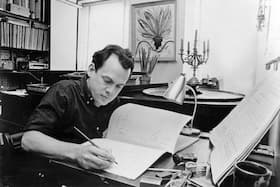

Samuel Barber © Wikipedia

The fourth opera to be awarded the Pulitzer was Samuel Barber’s Vanessa. The opera received its premiere at the Metropolitan Opera under the baton of Dimitri Mitropoulos, with sets designed by Cecil Beaton. Following its Met premiere, the opera then went to the Salzburg Festival where it was the first American opera presented there. The libretto for the opera was written by two-time Pulitzer winner Gian Carlo Menotti, who also directed the Met premiere. In a cold northern mansion, Vanessa awaits the return of Anatol, who left her 20 years ago. A man arrives and Vanessa is convinced it’s Anatol, but it is Anatol Jr., his father having died. Vanessa’s niece, Erika, falls in love with Anatol Jr., and is seduced by him. When Anatol Jr. marries Vanessa and they leave for Paris, Erika closes up the mansion just as Vanessa did and starts her own wait for the return of her love.

Samuel Barber: Vanessa, Op. 32 – Act III: Scene 2: No, I must never say that name again (Andrew Matthews, Erika; Lima Philip, Nicholas; Ukraine National Symphony Orchestra; Gil Rose, cond.)

John La Montaine © The New York Times

The final award-winner for the 1950s was John La Montaine who won in 1959 for his Piano Concerto No. 1, Op. 9, In Time of War. The work was noted for being both intensely dramatic and lyrical, with one writer labeling him a ‘modern romantic.’

John La Montaine: Piano Concerto No. 1, Op. 9, In Time of War

The 1950s winners were more alike than different. Atonality, although it was rife in the musical world, did not hold a place in the Pulitzer Prize winners and a fondness for lyricism, even of a hard-hitting variety, seemed to hold sway.

Next, the 1960s, 1970s and 1980s!

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter